노먼 레브레히트 칼럼 | 맨체스터의 마리온

맨체스터의 마리온

말러 교향곡 1번에 영감을 준 뮤즈, 이들은 왜 스캔들에 그쳤나

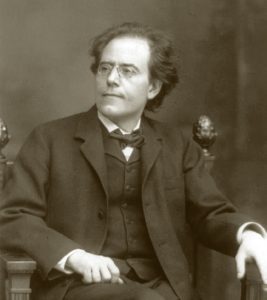

2011년 말러 전곡 연주 시리즈를 위해 독일 라이프치히를 방문했다. 그곳에서 나는 말러의 첫 번째 교향곡에 영감을 준 어느 여성에 대한 새로운 연구 자료를 우연히 발견했다. 말러 추종자들 사이에는 이미 유명했던 두 사람의 관계는 사실상 스캔들에 가까웠다.

1885년, 한 육군 대위가 자신의 조부인 카를 마리아 폰 베버(1786~1826)의 미완성 오페라 ‘세 사람의 핀토(Die Drei Pintos)’를 들고 라이프치히 오페라 부지휘자였던 말러를 찾아간다. 말러는 이 작품을 완성하려 했던 걸까? 승승장구하던 이십 대 중반의 말러는 이내 잉크로 흠뻑 젖은 악보를 들고 폰 베버 남작가(家)로 달려간다. 그는 그곳에서 저녁 식사를 함께하고 남작가 아이들을 위한 자장가도 작곡했다. 오래지 않아 말러는 대위의 아내와 맹렬한 사랑에 빠졌다.

이뤄지지 않은 사랑

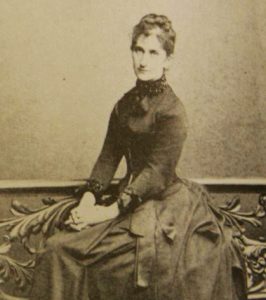

남편보다 16살이나 어리고, 말러의 또래에 훨씬 가까웠던 마리온 폰 베버 남작 부인은 군인 사회 속 부적응자나 다름없었다. 그녀 역시 말러처럼 유대인이자 예술가였고, 또한 지식인이었다. 심야의 피아노 2중주 공연에서 마리온은 말러에게 의도적 선언문과도 같은 교향곡을 작곡하라며 설득했고, 자정이 넘은 어느 날 밤 그는 1악장을 안고 돌아왔다. 얼마 뒤 두 사람은 함께 도피하여 다른 곳에서 새로운 삶을 시작하기로 결심한다. 말러는 기차표를 사고 승강장에서 연인을 기다렸지만, 마리온은 끝내 나타나지 않았고 그 뒤로 그녀의 남편은 정신을 놓아 버렸다.

라이프치히를 방문한 영국인 작곡가 에델 스미스(1858~1944)는 이 모든 소식을 듣곤, 자신의 회고록에 다음과 같이 적는다. “말러는 사랑에 빠졌고 … 그의 열정은 화답 받았다. 추악했던 그에게 악마 같은 매력 또한 있었기에 가능했던 일이다. 베버 대위는 이를 가능한 한 오랫동안 못 본 체했다. 이런 스캔들이 발각되면 군대를 떠나야 했기 때문이다. 그러던 어느 날 드레스덴으로 향하던 도중 그는 갑자기 웃음을 터뜨리며 권총을 뽑아 들고 스위스의 전설적인 용사처럼 좌석 사이의 머리 받침대에 총을 쏘기 시작했다.”

베버 대위는 제압되어 정신 병원으로 이송되었고, 말러는 새로운 직장을 찾아 프라하에 정착한다. 그는 더 이상 마리온으로부터 아무런 연락을 받지 못했지만, 그녀는 한참 뒤 작곡가 R. 슈트라우스와 네덜란드 지휘자 빌럼 멩엘베르흐(1871~1951)가 방문하자 아쉬운 듯이 말러를 추억했다. 마리온은 그들에게 말러가 자신에게 남긴 악보에 대해 말했는데, 멩엘베르흐가 듣기로는 (잘못 들었을 가능성이 높지만) 말러가 알려지지 않은 교향곡 네 편을 포함한 악보를 그녀의 집에 남겨 두었다고 했다. 마리온은 1931년 사망했고 모든 비밀이 담긴 저택은 연합군의 포격 때문에 파괴되고 말았다. 이러한 기억의 편린들로 인해 말러의 전기 작가들은 마리온을 그저 소도시의 따분한 육군 대위의 아내, 독일판 마담 보바리 정도로만 여겨왔다. 하지만 이제, 마리온이 말러의 부상에 있어 얼마나 중요하고도 흥미로운 존재였는지를 확인할 차례이다.

마리온의 정체

카를 마리아 폰 베버

마리온은 다름 아닌 영국 맨체스터 출신으로, 그의 아버지인 독일계 유대인 아돌프 슈바베는 650명의 직원이 근무하던 방직 공장을 운영했다. 마리온의 가족은 맨체스터에서도 독일어를 쓰던 부르주아 계급에 속했다. 어머니인 마틸데 슈바베는 의료계에서 저명한 여성인권 운동가이자 어린이병원 설립자인 루이스 보르하르트(1813~1883)와 친구였으며, 부부는 프리드리히 엥겔스(1820~1895)와 저녁 식사를 하던 사이였다. 또한 1858년 찰스 할레(1819~1895)가 잉글랜드 최고의 오케스트라를 시작했을 때 그를 지원하기도 한다. 토머스 칼라일(1795~1881)과 플로렌스 나이팅게일(1820~1910)도 옥스포드 로드 313번지에 있는 그들의 집을 방문했었다.

1856년 태어난 두 사람의 딸 마리온은 위대한 바이올리니스트 요제프 요아힘의 연주회 반주를 할 정도로 피아노를 훌륭하게 연주했다. 1868년 아내와 보르하르트 박사 사이의 염문을 알게 된 아돌프가 고국으로 돌아가며 가족이 뿔뿔이 흩어지기 전까지, 마리온은 북부 공장 지대 속에서 문화적 목가의 시간을 보냈다.

아버지의 부재 속에서 청소년기를 보낸 마리온은 이후 베를린에서 아버지와 재회하고, 음악가 집안의 후계자로 귀족 작위가 있으며 육군에 몸 담은 폰 베버 대위를 만나게 된다. 가톨릭 세례를 받은 그녀는 대위와 혼인을 한 뒤 세 명의 자녀를 낳고, 공연을 마친 음악가들을 초대해 제복을 입은 하인들로 하여금 빈티지 샴페인을 대접하며 호화롭게 가정을 꾸려간다. 마리온은 남편의 군인 사회에는 아무런 관심도 보이지 않았다.

마리온에게 첫눈에 반한 말러는 그녀에 대해 ‘아름다운 사람이자… 상대가 어리석은 짓을 하도록 유혹하는 이’라고 묘사한다. 그는 이어서 그녀가 ‘음악에 재능이 넘치고, 총명하며, 패기 넘치는 성품이 자신의 삶에 새로운 의미를 주었다’고 언급했다. 이 ‘의미’라는 것은 명백하게도 그의 첫 번째 교향곡을 말한다. 마리온은 말러의 영감이었던 것이다.

사랑의 고통을 담은 선율

그렇다면 마리온은 왜 말러와 도망치지 못한 걸까? 그녀의 가정사는 그녀가 자신으로 인해 어머니의 명예를 실추시키는 일을 피하려면 무슨 일이든 했을 것이라 말하고 있다. 말러로서는 다시는 결혼한 여성을 사랑하지 않을 것이었다.

그러나 마리온의 영향력은 오래 지속되었다. 말러의 교향곡 1번은 4분여 간의 주제 없는 도입부, 아이의 죽음과 선술집 춤곡을 결합하는 문제적 장송 삽입부로 온갖 규칙을 어겼다. 최근 일터에 복귀한 나는 그의 교향곡에서 이전에 의심했던 것보다 더 많은 유대인의 요소를 발견했다. 도입부의 더블베이스 솔로는 분명 단조로 바꾼 자장가 ‘자크 형제(Frère Jacques)’처럼 들린다. 이 자장가는 이스라엘에서 ‘여기저기에서(Yamin u-semol)’로 알려진 유대인 곡이기도 하다. 자크 형제에는 4박자가, 말러의 곡에는 5박자가 쓰였을 뿐이다. 교향곡 역사상 처음으로 말러는 하나의 악구에 두 개의 메시지를 넣었다.

그 뒤를 잇는 선술집 춤곡은 유대인 민속 음악인 클레즈머 춤곡인데, 브로드웨이의 유대인 뮤지컬 ‘지붕 위의 바이올린’의 후렴구인 ‘내가 부자라면’처럼 들리기도 한다. 아이의 장례와 선술집 소란스러움의 결합은 끔찍한 유아 사망률에 대한 대중의 무관심을 지적하는 것이기도 하다.

말러는 이해할 수 없는 색슨족의 도시 속, 유대계 이방인이었던 마리온의 매력에 사로잡힌 채 이 교향곡을 작곡했다. 이들의 사랑은 마리온이 들었던 선조의 선율로 표현되었다. 말러의 교향곡 1번은 그가 작곡한 어느 곡보다 더욱 유대인 음악의 성질을 띠고 있다. 동시에 이는 몹시도 강렬한 사랑과, 결코 다시는 입 밖으로 꺼낼 수 없을 정도로 고통스러웠던 거절에 대한 헌사이다.

19세기 라이프치히

Marion from Manchester

노먼 레브레히트 칼럼의 영어 원문을 함께 제공합니다

Visiting Leipzig for a Gustav Mahler cycle in 2011, I stumbled across some new research into the woman who inspired his first symphony. Their connection is well known to Mahlerians, indeed scandalous.

Mahler, junior conductor at the Leipzig Opera in 1885, was approached by an army captain with an uncompleted opera by his grandfather, Carl Maria von Weber. Might he have a go at finishing Die Drei Pintos? Mahler, mid-20s and upwardly mobile, was soon dashing over to Baron von Weber’s with sheets of ink-wet score. He stayed for dinner and wrote a bedtime lullaby for the Weber children. Before long he was madly in love with the captain’s wife.

Baroness Marion von Weber, 16 years younger than her husband and much closer to Mahler’s age, was a social misfit in military circles. Like Mahler, she was Jewish, an artist and an intellectual. In late-night duets at the piano she urged Mahler to write a symphony, a statement of intent. One night as midnight struck, he came round with the first movement. Before long they decided to elope and start life together some place else. Mahler bought train tickets and waited for his beloved on the platform. Marion never showed up. Her husband, soon after, went mad.

An English visitor to Leipzig, the composer Ethel Smyth, heard all about it. Mahler, she wrote in her memoirs, ‘fell in love … and his passion was reciprocated – as well it might be, for in spite of his ugliness he had demoniacal charm. A scandal would be mean leaving the army and Weber shut his eyes as long as was possible. One day, travelling to Dresden, Weber suddenly burst out laughing, drew a revolver and began taking William Tell-like shots at the headrests between the seats.’

Weber was straight-jacketed off to a mental home and Mahler landed a new job in Prague. He had no further contact with Marion, although she remembered him wistfully of him when the composer Richard Strauss and the Dutch conductor Willem Mengelberg came visiting in later years. Marion told them that Mahler had left her some music sheets including, Mengelberg heard (more likely misheard), four unknown symphonies. Marion died in 1931 and the mansion with all its secrets was destroyed in Allied bombing.

From these wisps of memory, Mahler biographers have concluded that Marion was a bored army wife in a market town with nothing much else to do, Madame Bovary with apple strudel. We now know that she was both more interesting and more important to Mahler’s emergence.

Marion, it turns out, came from Manchester, where her German-Jewish father, Adolf Schwabe, owned a textile factory with 650 employees. The family were part of the city’s German-speaking bourgeoise. Her mother Mathilde befriended the children’s hospital founder Louis Borchardt, a noted campaigner for women’s rights in the medical professions. The Schwabes dined with Friedrich Engels and supported Charles Hallé when he started an orchestra in 1858, the best in England. Her Thomas Carlyle and Florence Nightingale visited their home at 313 Oxford Road.

Their daughter Marion, born in 1856, played the piano well enough to accompany the great violinist Joseph Joachim in recital. It was a cultural idyll among the northern smokestacks until the family fell apart in 1868 when Adolf heard that his wife was having an affair with Dr Borchardt and returned to his homeland.

A fatherless adolescent, Marion joined Adolf in Berlin, where she met Captain von Weber, a musical heir with an aristocratic title and an army career. Accepting Roman Catholic baptism, she married the captain, gave birth to three children and ran a lavish household where musicians, welcomed after their concerts, were served vintage champagnes by liveried servants. She showed no interest in her husband’s officers mess. Mahler was smitten by Marion on sight, describing her as ‘a beautiful person…. the sort that tempts one to do foolish things’. He went on to say that her ‘musical, radiant and aspiring nature gave my life new meaning’. The ‘meaning’ is evidently his first symphony. She was his inspiration.

Why did Marion fail to abscond with him? Her history was such that she would have done anything to avoid inflicting her mother’s disgrace on her own children. Mahler, for his part, would never fall in love again with a married woman. Her influence, however, endures. Mahler’s first symphony breaks all sorts of rules with a four-minute themeless intro and a troubling funeral episode that conjoins a child’s death to a pub dance. I have returned to the work recently and found more Jewish elements than previously suspected. The double-bass solo at the start of the funeral movement is easily recognized as the lullaby Frère Jacques converted into a minor key. But it is also a Jewish melody, known in Israel as ‘yamin u-semol’, left and right. Frère Jacques has four beats. The Mahler theme has five. For the first time in symphonic history Mahler encodes two messages in the same phrase.

The pub dance that succeeds it is a klezmer dance, which you may recognise as the refrain of ‘If I Were a Rich Man’ in Broadway’s shtetl musical Fiddler on the Roof. The conjunction of child’s funeral and boozy romp is a comment on public indifference to appalling rates of infant mortality.

The symphony is composed under the spell of Marion from Manchester, a kindred Jewish alien in an uncomprehending Saxon city. Their love is expressed in ancestral melodies that Marion knew by ear. Mahler’s first symphony has more Jewish music than anything else he would ever write. It’s his tribute to a love so powerful and a rejection so painful that he never spoke of it again.

글 노먼 레브레히트

영국의 음악·문화 평론가이자 소설가. ‘텔레그래프’지, ‘스탠더즈’지 등 여러 매체에 기고해왔으며, 지금 이 순간에도 자신의 블로그(www.slippedisc.com)를 통해 음악계 뉴스를 발 빠르게 전한다