노먼레브레히트 칼럼 | SINCE 2012

영국의 평론가가 보내온 세계 음악계 동향

클렘페러와의 조우

대체 불가 20세기 명지휘자의 말년

여느 시상식 저녁 식사 도중 고악기 오케스트라 단장 옆에 앉았던 나는 그가 일반적으로 경시하는 지휘자에 대해 이야기를 나누게 됐다. 영국 필하모니아 오케스트라 초창기 시절에 대해 기억하는 게 있냐고 묻자, 갑자기 단장의 눈에 생기가 돌았다. “오토 클렘페러(1885~1973)가 있죠. 아무도 그처럼 단원들이 그런 음색을 낼 수 있게 만들지 못했어요.”

누구에게든 공평한 사이먼 래틀로부터도 비슷한 의견을 들은 적이 있다. 필하모니아 오케스트라에서 지휘하던 당시 래틀도 이렇게 말했다. “아무리 노력해도 단원들 손가락에서 클렘페러의 소리를 지워낼 수 없습니다.”

관객보다는 관계자들에게 사랑받은 사람

지금으로부터 50년 전 7월, 클렘페러는 스위스 자택에서 딸 로테의 간병하에 88세의 나이로 눈을 감았다. 홀로 삶을 꾸려간 매력적인 인물이었던 로테 역시 20년 전 7월에 그 집에서 삶을 마감했다.

워너 클래식은 클렘페러의 오케스트라 녹음을 총 95장의 CD로 발매했다. 물론 이것은 전체를 포괄한 개수가 아니다. 전율이 느껴지는 코번트가든의 ‘피델리오’를 포함한 오페라 및 오라토리오 음반은 오는 10월 발매될 예정이다. 1950년대 중반부터 1960년대 후반까지, 기록상 클렘페러는 가장 다작한 지휘자로 꼽힌다. 1950년경인 모두가 클렘페러는 이제 끝났다고 생각했으나, 딸 로테 덕분에 그의 이야기는 놀라운 음악적 부활을 이룩했다.

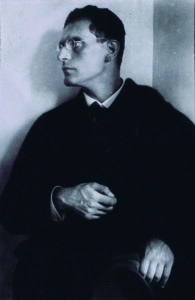

함부르크에서 성장한 클렘페러는 20세 때 오스카 프리드(1871~1941)의 말러 교향곡 2번 연주에서 무대 밖의 금관 악기 파트를 지휘했다. 말러(1860 ~1911)는 그에게 “소리가 올바르게 느껴지지 않는다면, 바꾸십시오”라며 해석에 대한 여러 조언을 주었고, “클렘페러는 지휘자가 될 운명을 타고났다”고 언급한 쪽지도 전달했다. 아첨꾼 브루노 발터(1876~1962)만큼 말러와 가까운 사이는 아니었지만, 열정적이고 추진력이 있으며 자해에 가까울 정도로 올곧은 영혼의 소유자였던 클렘페러는 말러와 심적으로 더욱 진실한 관계였다. 영국 텔레비전 프로그램에 출연한 클렘페러는 이렇게 말한 바 있다. “발터 선생이 도덕주의자라면 저는 부도덕주의자입니다.”

쾰른의 음악 감독이었던 그는 1917년 한스 피츠너(1869~1949)의 오페라 ‘팔레스트리나’의 두 번째 공연 지휘를 맡는다. 발터가 몇 개월 전 뮌헨에서 전 세계 초연을 했던 바로 그 작품이었다. 두 공연을 모두 관람한 작곡가 베르톨트 골트슈미트(1903~1996)는 음표로 결합했다는 공통점만 있는 별개의 두 오페라를 본 기분이라 설명했다.

1927년부터 1931년까지 클렘페러는 베를린에 위치한 크롤 오페라 극장을 새하얀 배경과 대담한 무조성 음악으로 무장한 현대 오페라의 분만실로 탈바꿈시킨다. 히틀러로 인해 추방당한 그는 미국에서 뉴욕 필하모닉과의 공연을 얻어냈지만, 말러 2번 교향곡 ‘부활’ 공연을 진행한 카네기홀의 객석은 절반이나 비어 있었다. 이후 클렘페러는 로스앤젤레스로 조용히 떠났다. 이에 한 음악계 관계자는 격분하여 말했다. “저희 아주 잘 지내고 있잖아요. 오늘부터 저의 성 말고 이름인 ‘산드라’로 불러주세요, 저는 오토라 부를 테니.” 클렘페러는 이렇게 답했다(고 로테가 내게 말했다). “그렇게 부르십시오. 하지만 저는 가지 않을 겁니다.”

든든한 딸과 함께한 말년

생사를 건 뇌종양 수술로 클렘페러는 몸 한쪽이 마비되고 언어 장애를 갖게 된다. 이어진 조울증의 발병으로 그는 정신 병원에 입원했지만, 담을 넘고 도주를 시도했다. 그는 또한 여성에게는 위험한 인물이었다. 안나 말러(1904~1988)는 클렘페러에게 바흐 칸타타의 악보에 대해 물었더니, 동작을 멈추고 명쾌한 답을 얻을 때까지 그가 테이블을 돌며 자신을 쫓아왔다고 말했다. 아버지의 침실에 아침을 챙겨주러 간 로테는 클렘페러가 이름도 기억하지 못하는 그의 옛 동반자를 소개받곤 했다. 한번은 베갯머리에서 담뱃불을 위스키 잔에 끄려다 본인 몸에 불을 지른 적도 있다. 그는 응급실 단골이었다.

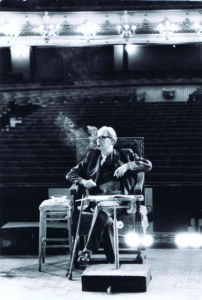

오토 클렘페러

종전 후, 그는 부다페스트 오페라 하우스에서 세 시즌 동안 지휘를 맡았지만, 공산주의자로 낙인이 찍혀 미국 여권을 몰수당했다. 회생 불능 상태가 된 60세의 그에게 세 명의 구세주가 나타난다. 똑똑한 법정 대리인 로널드 윌포드(1927~2015)는 클렘페러를 미국 오리건주 포틀랜드로 보내, 한적한 곳에서 자신감 회복을 도왔다(윌포드와 로테 사이에 뭔가 있었다고 들었으나, 로테 본인은 확답을 거부했다). 헤르베르트 폰 카라얀과 명성을 떨쳤던 필하모니아 오케스트라를 간절하게 교체해야만 했던 EMI 제작자 월터 레그(1906~1979)는 클렘페러를 런던으로 불러들였다. 지휘자와 오케스트라는 첫눈에 합이 맞았고, 그렇게 전설이 탄생했다. 오직 토머스 비첨(1879~1961) 정도가 더 많은 음악적 일화를 가지고 있다.

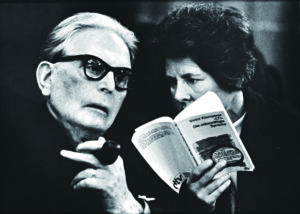

로테는 쓸데없이 시간을 빼앗고 사람을 조종하는 사기꾼 같은 이들로부터 아버지를 보호하며 그의 곁을 지켰다. 로테는 내게 빽빽한 세 쪽의 편지를 보내기도 했는데, 이는 표리부동한 레그를 위해 엘리자베트 슈바르츠코프(1915~ 2006)가 정성들여 작성한 그의 회고록의 내용을 수정하는 글이었다. 녹음 도중 “로테, 이건 사기다!”라고 외치는 격분한 클렘페러를 위해 로테는 필요하다면 레그에 맞서며 마치 그의 아버지처럼 신랄한 유머가 가미된 엄격함을 보여주었다. 클렘페러 옆에 앉아 있는 든든한 로테의 모습은 영국 국립 초상화 미술관에도 걸려있다.

오토 클렘페러와 로테 클렘페러

클렘페러가 남긴 명품 녹음들

워너 클래식이 선보이는 제단과도 같은 1백여 장으로 구성된 음반물에는 명연주로 꼽히는 곡이 여럿이고 최악은 드물다. 베토벤의 서곡 모음은 거의 교향곡 전집과 같이 황홀하다. 예후디 메뉴인(1916~1999)의 베토벤 바이올린 협주곡 음반에는 작곡가의 기벽과 숭고한 목표를 향한 공통된 믿음이 모두 압축되어 있고, 클렘페러는 음악으로 그 무의식을 전달한다. 클렘페러의 브루크너가 브람스보다 훨씬 더 중요한지에 대한 음악가들의 논쟁은 영원할 것이다. 런던의 관객들을 브루크너 마지막 교향곡에 빠져들게 한 것은 분명 그의 능력이었고, 이는 일종의 세례와 같은 경험이었다. 그의 하이든과 모차르트는 결코 예측할 수 없게 흐르는 가운데 우스꽝스럽기도 하며 애처롭기도 하다. R. 슈트라우스는 준(準) 근대적인 소리를 내며, 스트라빈스키와 차이콥스키는 한날한시에 태어나 분리된 샴쌍둥이 같다. 그 어떤 거장도 클렘페러의 방식으로 음악을 재창조할 수는 없다.

클렘페러는 말러 교향곡 2·4·7·9번만 녹음했으며, 나머지는 가치가 없다며 퇴짜를 놓았다. 베르톨트 골트슈미트가 교향곡 3번의 녹음을 마치도록 그를 설득했으나, 클렘페러는 골똘히 듣고는 신화 속 어깨에 지구를 짊어진 거인, 아틀라스의 모양새처럼 어깨를 으쓱해 버리고 만다. 이번 음반에 포함된 ‘대지의 노래’ 단편 연주는 녹음실에서 만난 적도 없는 크리스타 루트비히(1928~2021), 프리츠 분더리히(1930~1966)와 함께한 것으로 비할 데 없는 명반이다.

말년에 클렘페러는 마블 아치 예배당(Marble Arch Synagogue)에서 열리는 유대인의 대속죄일 예배 ‘욤 키푸르’에 다니엘 바렌보임을 끌고 간다. 위대한 신비를 해석하는 사람에게는 믿음이 필수적이라고 그는 주장했다. 클렘페러의 히브리어 이름은 ‘주는 사람(giver)’을 뜻하는 ‘나탄(Nathan)’이다. 우리 모두는 클렘페러에게 영원한 빚을 졌다.

번역 evener

노먼 레브레히트 칼럼의 영어 원문을 함께 제공합니다

본 원고는 본지의 편집 방향과 일치하지 않을 수 있습니다

Meet the Klemperers

Sitting at an awards dinner next to the leader of a period-instruments orchestra, we fell to talking conductors whom she generally disparaged. I asked what she remembered of her early years in the Philharmonia Orchestra. Suddenly, her eyes glistened. ‘We had Otto Klemperer,’ she said. ‘Nobody ever made us sound like that.’

I heard a similar appreciation from Sir Simon Rattle, no respecter of old lions. ‘Try as I might’ said Rattle when conducting the Philharmonia, ‘I could not get that Klemperer sound out of their fingers.’

Klemperer died 50 years ago this July, aged 88, cared for by his daughter Lotte at their Swiss home. Lotte, a captivating character in her own right, died there 20 years ago this July.

A Warner Classics box of Klemperer orchestral recordings has been issued on 95 CDs. It is by no means comprehensive. A further box of opera and oratorio discs, including the electrifying Covent Garden Fidelio, will follow in October. From the mid-1950s to the end of the 1960s, Klemperer was among the most prolific conductors on record. Yet around 1950 everyone thought he was finished. His story, thanks to Lotte, is one of the most remarkable music resurrections.

Raised in Hamburg, aged 20, Klemperer conducted the offstage band in Oskar Fried’s performance of Mahler’s second symphony. Mahler gave him tips on interpretation – ‘if it doesn’t sound right, change it’ – and a note saying he was ‘predestined for a conductor’s career’. Although never as close to Mahler as the fawning Bruno Walter, Klemperer was truer to him in spirit – impassioned, impulsive and high-principled to the point of self-harm. ‘Dr Walter is a moralist,’ said Klemperer on British TV. ‘I am an immoralist.’

As music director in Cologne, he conducted the second run of Pfitzner’s Palestrina in 1917, months after Walter gave the world premiere in Munich. The composer Berthold Goldschmidt who saw both, said it was like hearing two different operas, conjoined only by the notes.

In Berlin, from 1927 to 1931, Klemperer turned the Kroll Opera into the maternity ward of modern opera, with all-white backdrops and daring atonalities. Exiled by Hitler, he secured a concert with the New York Philharmonic, only to perform Mahler’s Resurrection symphony to a halfempty Carnegie Hall. Klemperer slunk off to Los Angeles. ‘We’re getting on so well,’ gushed a musical administrator, ‘from today you can call me Sandra and I shall call you Otto. ‘You may call,’ said Klemperer, ‘but I will not come.’ (Or so Lotte told me.)

Life-saving surgery for a brain tumour left him with speech defect and paralysed down one side. Eruptions of manic depression put him in a mental home, where he vaulted the wall and went on the run. He was a menace to women. Anna Mahler told me he chased her round a table until, asking him about a score marking in a Bach cantata, she stopped him in his tracks and obtained a lucid answer. Lotte, when she brought him breakfast in bed, would be introduced to his previous night’s companion, whose name he had forgotten.

Once, dousing a cigarette in a bedside whisky glass, he set fire to himself. He was a regular visitor to emergency departments.

After the war he conducted three seasons at Budapest Opera only to be branded a Communist and have his US passport confiscated. At 60, he was a write-off. Three saviours came forward. A smart agent, Ronald Wilford, sent him to conduct in Portland, Oregon, to recover confidence away from the hubbub (I heard Wilford had a fling with Lotte, but she refused to confirm). The EMI producer Walter Legge summoned him to London, desperately needing to replace Herbert von Karajan with his all-star Philharmonia. Conductor and orchestra clicked on first sight. A legend was born. Only Thomas Beecham is the subject of more musical anecdotes.

Lotte was there, protecting him from shysters, time-wasters and manipulators. She wrote me three closely-spaced pages of factual corrections to Elisabeth Schwarzkopf’s doting memoir of the duplicitous Legge. Exasperated at a record session he shouted, ‘Lotte, ein Schwindel!’ (a swindle). Lotte stood up to him when required, displaying something of her father’s rigour, laced with a caustic humour. She sits with him unflinching on a wall at the National Portrait Gallery in London.

In Warner’s catafalque of nearly a hundred CDs, the musical highlights are legion, the low points infrequent. A set of Beethoven overtures is almost as thrilling as the complete symphonies. Menuhin’s recording of the Beethoven violin concerto encapsulates both men’s quirks, their common belief in a higher purpose. Klemperer conveyed the unconscious in music.

Musicians will argue forever whether Klemperer’s Bruckner is more important than his Brahms. He gave London its first immersion in Bruckner’s last symphonies, a baptismal experience. His Haydn and Mozart are alternately frisky and lugubrious, never predictable. Richard Strauss is made to sound quasi-modern. Stravinsky and Tchaikovsky are Siamese twins, separated at birth. No maestro ever reimagined music in Klemperer’s way.

He recorded just four Mahler symphonies – 2, 4, 7 and 9 – rejecting the rest as unworthy. Berthold Goldschmidt persuaded him to sit through his recording of the third symphony. Klemperer listened intently then, like Atlas, shrugged. His piecemeal performance in this box of Das Lied von der Erde, with Christa Ludwig and Fritz Wunderlich who never met in studio, has no equal on record.

In his last years he dragged Daniel Barenboim to a Yom Kippur service at Marble Arch Synagogue. Belief, he insisted, was essential to an interpreter of great mysteries. Klemperer’s Hebrew birth-name was Nathan, the giver. We remain forever in his debt.

글 노먼 레브레히트

영국의 음악·문화 평론가이자 소설가. ‘텔레그래프’지, ‘스탠더즈’지 등 여러 매체에 기고해왔으며, 지금 이 순간에도 자신의 블로그(www.slippedisc.com)를 통해 음악계 뉴스를 발 빠르게 전한다