노먼 레브레히트 칼럼 | SINCE 2012

영국의 평론가가 보내온 세계 음악계 동향

인간 라흐마니노프

아쉬웠던 탄생 150주년. 이를 달래는 새로운 전기가 출간되다

음악적으로, 세르게이 라흐마니노프(1873~1943) 탄생 150주년인 2023년은 실망스러운 해였다. 기념의 초점은 모두 네 곡의 피아노 협주곡과 ‘파가니니 주제에 의한 랩소디’를 하나의 공연에서 연주하는 업적에만 집중됐다. 피아니스트 유자 왕·데니스 마추예프·미하일 플레트뇨프가 각각 미국·러시아·스위스에서 이를 시도했으며 근육통에 비하면 찬사는 그다지 받지 못했다. 대체 무얼 위한 공연이었을까? 그리고 우리가 모르는 라흐마니노프에 대해 말해준 것은 무엇이었을까?

라흐마니노프는 오랜 시간 명성을 얻었고, 협주곡 중 두 곡은 매우 유명하여 모두에게 익숙한 인물이다. 남겨진 여러 사진에서 거대한 양손과 함께 멀쑥하고 뚱한 모습을 하고 있다. 그는 러시아 혁명 후 본인의 삶을 다시 세웠고, 미국과 유럽으로 떠나는 와중에 창작에 대한 열정을 잃었다. 인생의 마지막 3분의 1 동안 그가 작곡한 것은 여섯 작품이 전부였다. 조국을 잃은 그는 창의력마저 돌이킬 수 없을 만큼 상실했다.

우울하기보다 성실했던 사람

나탈리야와 세르게이

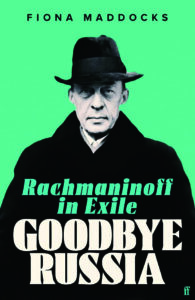

여기까지가 우리가 알고 있는 라흐마니노프인데, 영국의 음악 비평가 피오나 매독스는 새로 발간한 라흐마니노프의 전기 ‘굿바이 러시아-망명 중인 라흐마니노프’(2023)에서 이 가설에 맞선다. 라흐마니노프는 망명으로 인해 내리막길을 걷기보다, 일 년도 채 안 되어 경제적 안정성을 되찾는 놀라운 회복력을 보여주었다. 기가 죽기는커녕 그는 가정의 행복을 누렸고, 스포츠카를 몰았으며, 인류가 경험할 수 있는 모든 측면에서 끝없는 호기심을 유지했다. 그는 이상적인 저녁 초대 손님이었다.

부유했던 44세의 세르게이는 1917년 12월 23일 러시아 땅을 떠난다. 그는 모든 재산을 부동산으로 정리했으나 러시아 공산당이 이를 몰수하고 그의 저작권 또한 국유화했다. 빈털터리 신세로 덴마크 코펜하겐에 도착했는데, 아내 나탈리야가 장작불 앞에서 연기를 맞아가며 일을 하는 동안, 그는 유려하게 피아노 연주를 하며 생계를 이어갔다. 스칸디나비아 투어로 몸을 푼 라흐마니노프는 미국에서 25번의 리사이틀을 제안받았고, 비행기표를 구매하기 위해 돈을 빌렸다.

뉴욕에 도착한 그의 가족이 ‘호텔 네덜란드’에 체크인하자 손님이 몰렸다. 그 첫 손님 중에는 신랄하기로 유명한 프로코피예프도 있었는데, 라흐마니노프의 후배 격인 그는 라흐마니노프의 명성에 몹시 분개하고 있었다. 언론은 보스턴 심포니의 음악감독 자리를 거절한 라흐마니노프가 더는 지휘에 관심이 없다고 떠들었다. 대신 그는 작곡가로서 경력을 키우기 위해 학창 시절 작곡한 첫 번째 피아노 협주곡을 수정한다. 프로코피예프는 초연에서 라흐마니노프를 무대 인사를 피하려고 “아내 뒤로 숨는” 모습으로 묘사했다.

라흐마니노프가 돌아간 곳은 건반 앞이었다. 미국에서의 첫 시즌이 끝나갈 무렵 그에게는 비서를 고용하고 샌프란시스코만으로 여름휴가를 예약할 정도의 여유가 생겼다. 다음 피아노 협주곡 공연에 대한 초대장도 물밀듯이 밀려왔는데, 가장 끈질겼던 필라델피아의 두 음악감독 레오폴드 스토코프스키(1882~1977)와 유진 오르먼디(1899~1985)가 향후 작품에 대한 우선권을 가져갔다.

1926년 세상에 나온 네 번째 협주곡은 너무 길고 독창성이 없었다. 두 번째 악장의 거대한 선율은 동요 ‘눈먼 쥐 세 마리(Three Blind Mice)’와 비슷했다. 1934년에는 이에 대해 보상하듯 리스트와 브람스가 변주곡을 썼던 모티브를 활용하여 ‘파가니니 주제에 의한 랩소디’를 선보였다. 러시아 장송곡 ‘진노의 날’과 관련된 18번째 변주의 눈물 나게 감동적인 부분은 리스트와 브람스의 작품에서는 찾아볼 수 없는 것이었고, 그 성공은 즉각적이었다. 작곡가 본인은 농담처럼 “제 에이전트를 위한 곡입니다”라고 덧붙이곤 했다.

대양도 횡단한 넘치는 이타심

굿바이 러시아 – 망명 중인 라흐마니노프 피오나 매독스 저 £21│Faber & Faber

라흐마니노프의 마음속에서 러시아는 결코 멀어진 적이 없었다. 그는 고향에 두고 온 사촌에게 종종 편지를 하고, 현금과 생필품을 보냈다. 작곡가 니콜라이 메트너(1880~1951)에게는 5만 마르크, 절박한 오페라 극작가에게는 5백 프랑을 전달하기도 했다. 무엇보다도 1897년 자신의 교향곡 1번을 만취한 채 지휘해 3년간 젊은 라흐마니노프를 우울증 속에 빠뜨렸던 알렉산드르 글라주노프(1865~1936)가 망명하자, 그 역시 지원하였다.

피난처는 미국이었지만 라흐마니노프는 유럽에서도 매년 주요 공연을 진행했으며, 첫째 딸 이리나가 남편 표트르 볼콘스키 공작(1897~1925)과 함께 있는 파리도 방문했다. 공작은 1925년 아이가 태어나기 직전 28세의 나이로 갑작스레 유명을 달리했다. 매독스는 그가 광신도가 되어 정신병원에서 스스로 목숨을 끊었다고 밝히고 있다. 딸들을 돕기 위해 라흐마니노프는 파리에 출판사를 차리고 러시아 음악과 출판물을 제작했다. 여름철에는 가족과 함께 본인이 스위스 루체른 호숫가에 지은 저택에서 휴양했고, 그 저택을 자신과 아내의 세례명 첫 음절을 따서 ‘세나르(Senar)’라 불렀다.

그는 세나르에 젊은 음악인들을 즐겨 초대했다. 피아니스트 블라디미르 호로비츠(1903~1989), 바이올리니스트 나탄 밀스타인(1904~1992)이 단골손님이었는데, 밀스타인은 내게 이렇게 말한 적이 있다. “그 시절 작곡가는 과학, 자연, 철학 등 모든 것에 통달한 사람이었습니다. 우리는 몇 시간이고 이야기를 나눴고 라흐마니노프는 호로비츠보다는 저를 더 좋아했죠. 제가 피아니스트가 아니어서 그랬을지도 모릅니다.” 밀스타인은 자신이 라흐마니노프를 왁자지껄 웃게 할 수 있다고 주장했으니, 사진에서 보이는 그의 엄숙함은 진짜가 아니었다.

매독스는 라흐마니노프가 대서양을 가로지르며 운송해 온 여러 스포츠카에서 얻은 즐거움에 관해 설명한다. 제2차 세계대전은 그를 미국에 가두었고, ‘진노의 날’의 파편은 필라델피아 오케스트라를 위해 작곡한 ‘교향적 무곡’에 스며들었다. 흑색종 진단을 받고 전쟁 소식에 우울해하던 그는 일흔 번째 생일을 며칠 앞두고 1943년 3월 28일 눈을 감았다.

매독스의 새로운 전기는 라흐마니노프를 러시아나 미국에 속한 인물이 아니라 인류 전체에 속했으며 전 세계의 사랑을 받은 인물로 다시 그리고 있다. 블라디미르 푸틴 정권이 그의 유해를 송환하고 세나르의 저택을 매입하려 했으나, 다행히도 두 시도 모두 저지되었다. 라흐마니노프가 시대의 정치적 고통이나 민족 주체성에 대한 의문을 뛰어넘는 인물이라는 점은 분명하다. 말하자면 그는 위대한 작곡가이자 다정하고 연민 어린 사람이었다.

번역 evener

노먼 레브레히트 칼럼의 영어 원문을 함께 제공합니다

본 원고는 본지의 편집 방향과 일치하지 않을 수 있습니다

The 150th anniversary year of Sergei Rachmaninoff was a musical disappointment. Its highlight was the athletic feat of playing all four piano concertos and the Paganini Rhapsody in a single concert. Three pianists attempted this in America, Russia and Switzerland – Yuja Wang, Denis Matsuev and Mikhail Pletnev. They emerged with sore muscles and not much credit. What, after all, was the point? And what did it tell us about Rachmaninoff that we did not already know?

Rachmaninov has been famous for so long and two of his concertos so popular that everything about him seems familiar to the eye and ear. Tall, morose in most photographs and with huge hands, the composer rebuilt his life after the Russian Revolution, taking to the road in America and Europe and losing his creative spark along the way. In the remaining third of his life he produced just six scores. Together with his homeland, he suffered a crippling loss of imagination.

That is the Rachmaninov we think we know. ‘Goodbye Russia,’ a new biography by the British music critic Fiona Maddocks, challenges those assumptions. Far from being defeated by exile, Rachmaninov showed extraordinary resilience to recover financial security in less than a year. Rather than being downcast, he enjoyed domestic happiness, drove fast cars and maintained an insatiable curiosity in every aspect of human experience. He would have been an ideal dinner guest.

The Sergei Rachmaninoff who left Russia on December 23, 1917, was 44 years old, wealthy from three or four bestsellers. He had put all his rubles into the family estate, which was confiscated by the Communists who also nationalized his copyrights. He arrived penniless in Copenhagen, where his wife Natalya blackened her hands on wood-burning cookers while Rachmaninoff limbered his fingers up to play piano for a living. After a warm-up tour of Scandinavia, he received an offer of 25 recitals in America and borrowed money to pay for the fare. The family arrived in New York, checking in at the Hotel Netherland. Among his first visitors was the caustic Sergei Prokofiev, a generation his junior and bitterly resentful of Rachmaninoff’s fame. The press were told Rachmaninoff had turned down a Boston Symphony invitation to become music director, no longer interested in conducting. Instead, he revised his juvenile first piano concerto in the hope of expanding his composer portfolio. Prokofiev, at the premiere, described Rachmaninoff ‘trying to hide behind his wife’ to avoid a stage call.

He went back to the piano. By the end of his first season in America, Rachmaninoff could afford a secretary and book a summer retreat on San Francisco Bay. Invitations poured in for him to perform his second and third piano concertos, most persistently from Philadelphia where two music directors, Leopold Stokowski and Eugene Ormandy, secured first refusal on any future works.

His fourth concerto in 1926 turned out to be overlong and unoriginal. The second movement’s big tune resembled the nursery rhyme ‘Three Blind Mice’. Rachmaninoff made amends in 1934 with Rhapsody on a Theme of Paganini, exploiting a melody that Liszt and Brahms had furnished with variations. Neither, however, matched the tear-jerking tenderness of Rachmaninoff’s 18th variation, a meditation distantly related to the funereal Russian Dies Irae. Its success was instantaneous. ‘This one’s for my agent,’ quipped the composer.

Russia was never far from his mind. He wrote often to cousins left behind, sending cash and care packages. He gave the composer Nikolai Medtner 50,000 German marks, and sent 500 French francs to a desperate librettist. Kindest of all, he supported the exiled Alexander Glazunov, who had wrecked his first symphony in 1897 by conducting while drunk, plunging the young composer into three years of depression. Although America was his refuge, he maintained an annual presence in Europe, performing in prime concert halls and visiting Paris, where his older daughter Irina lived with her husband Prince Pyotr Volkonsky. In 1925, just before the birth of their child, Volkonsky died suddenly, aged 28. Maddocks reveals that the prince committed suicide at an asylum while in the grip of religious mania.

To support his daughters, Rachmaninoff set up a Paris publishing company to produce Russian books and music. In summer he gathered the family in a villa he built in Switzerland on the shores of Lake Lucerne. He named the house Senar, entwining the first syllable of his Christian name with his wife’s.

He liked to have young musicians stay at Senar. The pianist Vladimir Horowitz and violinist Nathan Milstein were regular guests. Milstein told me: ‘In those days a composer knew about everything – science, nature, philosophy. We would talk for hours. He liked me better than Horowitz – maybe because I wasn’t a pianist.’ Milstein claimed he could make Rachmaninoff laugh, uproariously. The photographic solemnity was a false front.

Maddocks recounts Rachmaninoff’s delight in a string of designer motor-cars that he shipped back and forth across the Atlantic. The second world war confined him to America. Fragments of the Dies Irae pervade his Symphonic Dances for Philadelphia. Diagnosed with melanoma and depressed by war news, he died on March 28, 1943, days short of his seventieth birthday.

The new biography reframes Rachmaninoff as a man of the world, belonging not to Russia or America, but to humanity as a whole. Vladimir Putin’s regime has tried to repatriate his remains and buy up his villa at Senar. Both bids have been mercifully resisted. Rachmaninoff, it has become clear, was bigger than the political torments of his time, bigger too than questions of national identity. Tout court, he was a great composer and a man of kindness and compassion.

글 노먼 레브레히트

영국의 음악·문화 평론가이자 소설가. ‘텔레그래프’지, ‘스탠더즈’지 등 여러 매체에 기고해왔으며, 지금 이 순간에도 자신의 블로그(www.slippedisc.com)를 통해 음악계 뉴스를 발 빠르게 전한다.