노먼 레브레히트 칼럼 | SINCE 2012

영국의 평론가가 보내온 세계 음악계 동향

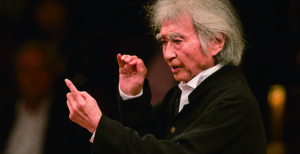

오자와 세이지를 기억하며 1935~2024

헌신적인 마에스트로 세대의 마지막 인물

©Holger Kettner

그는 여러 방면에서 최초이자 최후를 장식한 인물이었다. 그 이전에는 중국이나 일본 출신 지휘자 중 누구도 세계 정상급 오케스트라를 지휘한 적이 없으며, 그 이후로도 그의 영향력에 맞먹는 이 또한 없었다. 캐나다 토론토 심포니와 미국 샌프란시스코 심포니를 거친 오자와 세이지는 보스턴 심포니 오케스트라에서 무려 30년(1973~2002)간 음악감독으로 재임했다. 2002년 보스턴을 떠난 그에게는 빈 국립 오페라 극장이 음악감독직을 안겨주었다. 비록 오자와의 오페라 레퍼토리는 그가 구사하는 독일어 대화만큼이나 한정적이었지만, 그는 빈에게 매우 절실했던 활력을 불어넣어 주었다. 젠체하는 지휘자들로 가득한 시대에 오자와는 단단하고도 꾸밈없는 새로움을 보여주었다.

1945년 이후 일본이 보여준 서구 문화를 향한 위축적인 태도가 그에게는 없었다. 오자와는 오히려 양쪽 모두에 해당하는 자신의 유산을 자랑스럽게 간직했다. 당시 일본군이 세운 만주국에서 치과 의사의 아들로 태어난 그는 유년 시절 중국어를 구사했고, 마오쩌둥 사후에는 중국에 자주 방문하며 가족과 휴가를 보내거나 젊은 음악가를 대상으로 마스터클래스를 열기도 했다. 그는 어머니의 유해 절반을 생가 정원에 묻었으며, 자신을 이중 문화인(bi-cultural)으로 보았다.

거장에게 발탁된 젊은 시절

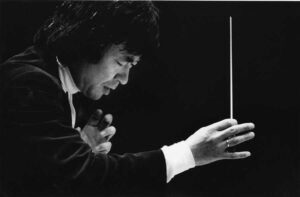

오자와 세이지와 레너드 번스타인(1980)

1941년 일본으로 돌아간 오자와는 스승 사이토 히데오(1902~1974) 밑에서 7년간 수학했으나(추후 오자와는 스승을 기리며 사이토 키넨 오케스트라를 창단한다), 15세에 럭비 시합에서 손가락 두 개가 골절되며 피아니스트의 꿈을 접게 된다.

오자와는 프랑스에서 지휘자 콩쿠르 1위를 한 덕분에 탱글우드에서 여름을 보내게 되는데, 이때 레너드 번스타인이 그를 뉴욕 필하모닉 부지휘자로 지명했고, 헤르베르트 폰 카라얀은 그를 베를린으로 불렀다. 오자와는 한쪽은 억압받는 오스트리아 나치 부역자, 다른 한쪽은 격식 없는 미국 유대인인 두 스승 사이에서 융합을 꾀했다. 카라얀은 정교함, 권위, 인격적 기품을 가르쳤고, 번스타인은 포디엄에서 춤을 추는 법, 음악을 타는 법, 흐름을 따르는 법을 가르쳐 주었다.

샌프란시스코에서 오자와는 밝은색의 장발 헤어스타일에 반전 티셔츠를 입었다. 보스턴에서는 알렉산드르 스크랴빈의 ‘불의 시(프로메테우스)’로 천장을 무지갯빛으로 수놓았다. 공연장에 가득 찬 격식 속에서 그는 베토벤 기념행사를 모르는 체하고, 비틀스의 곡을 부르며 새로운 유형의 지휘자로서 본을 보여주었다. 오자와의 음악적 취향은 절충적이나, 세련됐다. 그는 올리비에 메시앙의 폭발적인 교향곡 ‘투랑갈릴라’를 선보였고, 프랑스 아시시의 성 프란치스코의 평범한 삶을 다룬 오페라 ‘아시시의 성 프란치스코’를 초연했다. 오자와는 버르토크와 루토스와프스키, 풀랑크, 앙리 뒤티외, 스트라빈스키, 다케미쓰 도루를 아꼈다. 보스턴 심포니 재임 초반, 그는 다른 미국 오케스트라들이 부러워할 만한 매력을 뽐냈다.

보스턴 심포니의 전성기를 이끌다

©Boston Symphony Orchestra

오자와는 보스턴 도시에 체류하기를 거절하고 일본 도쿄에서 가족을 부양하며, 필요한 경우에만 태평양을 건넜다. 그의 영어는 거센 억양으로 실용 영어 이상은 절대 아니었지만, 음악가 대부분은 그의 요구를 이해했다. 항의하는 이들은 오래 가지 못했다. 오자와는 일선의 반체제 무리를 대수롭지 않게 넘기며 “스스로 무덤을 파고 있는 건 저들”이라 말했다. 그는 번스타인처럼 격이 없기도 했으며, 카라얀처럼 냉철하기도 했다. 대개 지휘봉 없이 지휘를 했는데, 이는 숭고한 분위기를 만들기 위해서였다.

공연이 끝나면 아사히 맥주 여섯 캔을 단숨에 마셨고, 음주 운전으로 체포된 적이 두 번 있었으나 모두 유야무야 잊혀졌다. 난관에 부닥친 음악가와 관계자들에게 그가 베푼 조용한 선행 또한 묻혔다.

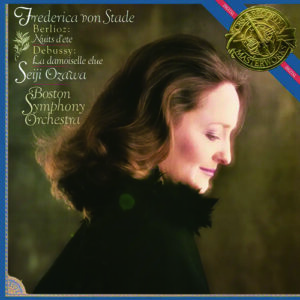

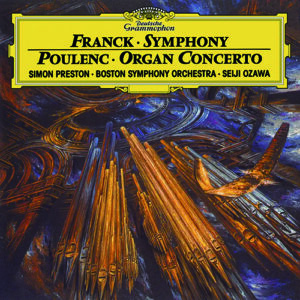

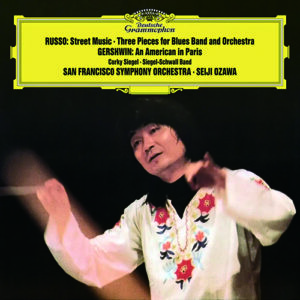

오자와의 오케스트라를 위해 그보다 많은 자금을 마련한 음악감독은 없었다. 그는 소니 그룹의 수장이었던 모리타 아키오, 그리고 음악가이기도 했던 오가 노리오가 할리우드 지분의 절반을 사들이는 동안 자문역을 했다. 그 답례로 오가는 탱글우드의 ‘세이지오자와홀’ 신축 비용인 1,000만 달러의 5분의 1을 기부했고, 보스턴 심포니 지휘권에 대해 100만 달러를 더 얹어 내놓았다. 소니가 전 세계에서 두 번째로 큰 음악 기업으로 발돋움하자 오자와가 산더미같이 음반을 내지 않을까 싶었지만, 실제로 그의 디스코그래피는 수수한 편으로 50여 개가 채 되지 않는다. 음반 중에는 ‘베를리오즈: 여름밤’(1984)➊, ‘프랑크: 교향곡 d단조’(1993)➋가 뛰어나다. 나는 특히 ‘루소: 블루스 밴드와 오케스트라를 위한 세 개의 소품’(1972)➌을 좋아하는데, 코키 시겔(1943~)의 하모니카 솔로는 누구든 꼭 들어봐야 한다.

멀리 떨어져 있었음에도 오자와는 보스턴 심포니에 헌신적이었다. 다른 지휘자들이 세 대륙을 건너다니며 일을 병행할 때도 그는 전통적인 마에스트로-오케스트라의 일부일처를 고수하며 독자적인 소리와 스타일을 닦아 나갔다. 심지어 보스턴에서의 마지막 해, 단원 중 절반이 공공연한 반항을 일으켰을 때도 그는 고집스럽도록 충실함을 유지했다.

삶을 갈무리 지으며

➊Sony G010003507242G

➋DG 4378272

오자와는 그와 같은 부류의 최후를 장식한 인물이기도 했다. 2002년 그가 떠난 이래로 보스턴 심포니는 제임스 러바인(1943~2021), 안드리스 넬손스(1978~)를 거치며 길을 잃었다. 이 두 지휘자는 보스턴 이외에도 다른 직을 동시에 맡고 있었다. 보스턴 심포니는 더는 놀라움이나 열풍을 만들어 내지 못했으며, 쇠락하는 산업의 또 다른 구독 호객 사업으로 전락했다. 클리블랜드 오케스트라, LA 필하모닉, 필라델피아 오케스트라는 계속해서 보스턴 심포니를 앞서 나갔다.

2010년 식도암으로 투병하던 오자와는 일본으로 돌아가 이따금 지휘봉을 들어 언어와 거리를 초월한 옛 우정을 키워 나갔다. 그는 몇 명의 제자를 양성했는데, 프랑스인 콘트랄토 나탈리 스투츠만(1965~)은 그 과정에서 지휘자로 발탁된 예외적인 인물이다. 스투츠만은 현재 조지아의 애틀랜타 심포니에서 음악감독으로, 바이로이트에서 객원지휘자로 활동하고 있다.

➌DG 4865339

오자와의 음악 유산은 그의 직업적 덧없음으로 인해서 제한적이다. 그가 익숙한 작품에 밝혀둔 불을 쬐고 새로운 작품에 부여한 열정을 확인하려면 무조건 공연장에 가야만 했다. 오자와는 자신의 방식을 결코 명료하게 표현하지 않았다. 소설가 무라카미 하루키와의 대담집에서도 그는 속을 내보이지 않는데, 이에 좌절한 하루키는 이렇게 적는다. “아닌 게 아니라 오자와 씨에게는 ‘오자와 어(語)’ 같은 게 있는데, 그것을 일본어 문장으로 바꾸는 게 간단하지 않다.(출처_ 도서 ‘오자와 세이지 씨와 음악을 이야기하다’/권영주 역)” 누군가는 그의 불명료함이 고의적이라 여길 것이다. 오자와는 지난 2월 도쿄에서 88세의 나이로 눈을 감았다.

오자와 세이지에게 음악이란, 단어나 음표 속에 있는 게 아닌 손과 눈의 교감이 만드는 천상의 영역에 있다. 손짓과 눈빛 안에 담겨 들숨과 날숨을 허용하는 존재, 그 본연의 모습으로.

번역 evener

노먼 레브레히트 칼럼의 영어 원문을 함께 제공합니다

본 원고는 본지의 편집 방향과 일치하지 않을 수 있습니다

Seiji Ozawa was the first of his kind and, in many respects, the last. No conductor from China or Japan ever commanded world orchestras before him, and none has since matched his impact. After entry jobs in Toronto and San Francisco, Ozawa was music director in Boston for just under three decades. When he left in 2002, the Vienna State Opera made him music director. Although his opera repertoire was as limited as his German conversation, Ozawa added a much-needed dynamism. In an era of peacock conductors, Ozawa brought an unfeigned and impenetrable exoticism.

Not for him the post-1945 cringe that Japan displayed towards western culture. Ozawa bore his twin heritages with pride. The son of a dentist in occupied Manchuria, he spoke Chinese as a child and visited China often after Chairman Mao’s death, holidaying with his family while giving masterclasses to young musicians. He buried half of his mother’s ashes in the garden of the family home. He considered himself bi-cultural.

Repatriated to Japan in 1941, Seiji worked seven years as a household servant for his music teacher, Hideo Saito (in time, he would create the Saito Kinen orchestra in his master’s memory). At 15 he broke two fingers in a rugby scrum, ending hopes of a piano career.

A conducting competition victory in France earned him a summer in Tanglewood, where Leonard Bernstein hired him as assistant with the New York Philharmonic. Herbert von Karajan called him to Berlin. Ozawa syncretized both of his mentors, the repressed Austrian Nazi and the unbuttoned American Jew. Karajan preached precision, authority, personal elegance. Bernstein taught him how to dance on the podium, to sway with the music, go with the flow.

In San Francisco, Ozawa wore flower-power shirts and shiny, long hair. He blew into Boston with Scriabin’s Poem of Fire, rainbow colours splayed across the ceiling. In the stuffiest of concert halls, he exemplified a new breed of conductor, one who ignored Beethoven anniversaries but sang Beatles songs. Ozawa’s musical tastes were eclectic, but tasteful. He performed an eruptive Messiaen Turangalila and premiered the composer’s opera on the uneventful life of Francis of Assisi. Ozawa liked Bartok and Lutosławski, Poulenc and Dutilleux, Stravinsky and Takemitsu. For the first half of his term, the Boston Symphony had a wow factor that other US orchestras could only envy. Ozawa refused to live in Boston, raising his family in Tokyo and commuting when required. His English was never more than functional, spoken in a comic-book accent. Most musicians grasped what he wanted; any who protested did not last long. ‘Those women are making their own graves,’ said Ozawa, shrugging off a pair of front-desk dissidents. He could be pally as Bernstein, callous as Karajan. He conducted mostly without a baton, the better to generate an ethereal ambience.

After a concert he could sink six Asahi beers. There were two arrests for driving under the influence, both hushed up. Also unreported were quiet acts of generosity to musicians and administrators who had fallen on hard times.

No music director raised more money for his orchestra. Ozawa acted as a sounding board to the heads of the Sony Corporation, Akio Morita and Norio Ohga, as they bought up half of Hollywood. In return, Ohga donated one-fifth of the $10 million cost of a new Ozawa Hall in Tanglewood and paid another million dollars for the privilege of conducting the Boston Symphony. Once Sony became the world’s second largest music company, it might have been expected that Ozawa would make stacks of records. Actually, his discography is modest, fewer than fifty releases. A 1984 Berlioz Nuits d’été and a 1993 Franck D minor symphony stand out. My own favourite is a 1972 William Russo piece for blues band and orchestra, with a harmonica solo by Corky Siegel that must be heard to be believed.

For all his remoteness, Ozawa was devoted to Boston. Where others held jobs on three continents, he upheld a traditional maestro-orchestra monogamy, burnishing an identifiable sound and style. Even in his last Boston years, when half the orchestra were in open rebellion, Ozawa stayed stubbornly loyal.

In this, too, he was the last of his kind. Boston, after his departure in 2002, lost its way with James Levine and Andris Nelsons, both of whom had parallel jobs elsewhere. The BSO no longer surprises or makes waves; it is just another subscription business in a failing industry. The orchestras of Cleveland, LA and Philadelphia outshine it week after week.

Stricken with esophageal cancer in 2010, Ozawa retreated to Japan, conducting sporadically and nurturing old friendships that transcended language and distance. He nurtured few protégés, with the exception of the French contralto Nathalie Stutzmann whom he spotted as a conductor in the making; she is now music director in Atlanta, Georgia, and a summer fixture at Bayreuth.

Ozawa’s legacy is limited by the ephemerality of his vocation. You had to be there to feel the fire he lit in familiar works and the passion he invested in the new. Ozawa never articulated his method. In a series of non-conversations with the novelist Haruki Murakami, he gave nothing away. ‘The maestro does speak his own special brand of Ozawa-ese, which is not always easy to convert to standard written Japanese,’ wrote the frustrated Murakami. One must assume his obfuscation was intentional. Ozawa died last month (Feb) in Tokyo, aged 88. Music, for Seiji Ozawa, lay not in words, nor even in notes, but in some supernal realm of hand and eye communication, a gesture and a look that allowed the music to in- and exhale, to be itself, to be.

글 노먼 레브레히트

영국의 음악·문화 평론가이자 소설가. ‘텔레그래프’지, ‘스탠더즈’지 등 여러 매체에 기고해왔으며, 지금 이 순간에도 자신의 블로그(www.slippedisc.com)를 통해 음악계 뉴스를 발 빠르게 전한다