노먼 레브레히트 | SINCE 2012

영국의 평론가가 보내온 세계 음악계 동향

이 가을, 피아니스트 4인 4색

남다른 레퍼토리로, 자신만의 세계관을 드러내는 이들과 대표 음반

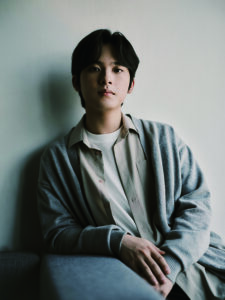

임윤찬

차이콥스키 ‘사계’

일류 아티스트가 삼류 음악을 연주하면 하찮은 방종 행위로 남거나 혹은 놀랍고 새로운 발견이 되기 마련이다. 이 앨범은 어느 쪽에 해당하는지 확인하기 위해 세 번을 들었다.

일류 아티스트가 삼류 음악을 연주하면 하찮은 방종 행위로 남거나 혹은 놀랍고 새로운 발견이 되기 마련이다. 이 앨범은 어느 쪽에 해당하는지 확인하기 위해 세 번을 들었다.

차이콥스키는 상트페테르부르크 음악 잡지의 연재물에서 한 해 열두 달에 해당하는 열두 곡의 피아노 소품을 썼다. 편집자는 작곡가의 관여 없이 각 소품에 시를 한 편씩 덧붙였다. 여기까지가 확인된 사실이다. 임윤찬의 경우, 해설에서 이 모음곡이 한 사람의 저물어가는 마지막 한 해를 어떻게 묘사하는지에 대한 우화를 풀어낸다.

당시 한창 ‘백조의 호수’를 작곡하던 차이콥스키는 이후 20여 년을 더 살았으며 죽음에 대한 긴박함이라고는 찾아볼 수 없었기에, 이 한국인 피아니스트의 충실치 못한 서술은 불편하다.

음악적 해석에 대해서는? 2022년 밴 클라이번 콩쿠르 우승자인 임윤찬(2004~)은 수십 년 만에 등장한 매력 넘치는 천상의 피아니스트다. 지금까지 라흐마니노프와 쇼팽 앨범에서 그는 틀린 적이 없었다.

‘사계’ 중 ‘1월’에서 그는 키치함의 끝에 다가서는데, 사실 임윤찬보다는 차이콥스키의 잘못이다. ‘3월’에서는 녹아내리는 눈 위의 깃털처럼 무중력의 경이로움을 연주하며, ‘6월’은 희망과 암울함, 그 사이 어딘가에 있다. ‘8월’은 난잡하게 뛰어오르는데, 이성으로부터의 도피 같기도 하다. 솟구치는 천재성으로 가득한 ‘10월’은 라흐마니노프가 앙코르로 즐겨 올리던 곡이기도 했다. 마지막 두 곡은 결단이 엿보이나, 설득력 있지는 않다.

임윤찬의 연주는 때로 눈부시지만 그의 언어적 상상과는 상충한다. 세 번째로 듣고 나서야 비로소 그 어떤 의제와도 관련 없이 그의 연주가 진심으로 만족스러웠다. 실망시키지 않을 앨범이다.

스티븐 오스본

슈베르트 소나타 D959 & ‘악흥의 순간’ D780

슈베르트 피아노 작품에 있어 알프레드 브렌델만큼 위엄을 떨쳤던 사람이 또 있을까. 그 덕에 다른 피아니스트들은 손가락에서 브렌델을 떨칠 수 없다며 불평하기도 한다. 브렌델이 슈베르트 후기 작품을 녹음하고도 20년도 더 흘렀으며, 필립스(Philips) 레이블에서 전례 없는 앨범을 낸지도 반세기가 지났지만, 여전히 그의 그림자는 길게 드리워져 있고, 우리 시대의 슈베르트 피아니스트로 확실하게 거듭난 도전자는 아무도 없었다.

스티븐 오스본(1971~)은 단연코 이 분야를 이끌고 있다. 베토벤 음반의 대표 주자인 이 스코틀랜드인은 후기 슈베르트 소나타 도입부에서 브렌델이 지켰던 감정적 중립을 무시하고 확신에 찬 명료하고 설득력 있는 해석을 내세운다. 첫 악장의 에너지는 자기 연민을 향해 과감하게 변화하는 두 번째 악장의 부드러움과 대조를 이룬다. 이내 절제된 비애로 후퇴했다가 후반부에 장난스러움이 다시 돌아온다. 오스본은 학계 다수의 추측과는 달리 이 작품이 죽음을 앞둔 사색이 아니라는 점을 확실하게 알려준다. 도리어 베토벤의 영역에 진출한 듯 보이는 그의 슈베르트는 단호하지는 않아도 여전한 야망으로 후기 소나타를 가득 채운다.

‘악흥의 순간’에서 그는 다소 일관성을 잃는다. 브렌델의 주특기였던 ‘빈’적인 신랄함도 훨씬 덜 나타나는데, 이는 오스본이 뚜렷하게 내면을 향하며, 자기 자신에게 집중하는 듯 깊은 명상에 빠진 채로 마지막 6번째 곡까지 이어진다. 하나의 음악 작품에서 자신만의 해답을 구하는 예술가적 감각은 누구에게나 있으며, 언제라도 유익한 청각적 경험이 된다. 오스본은 과거의 진부함을 넘어서며, 듣는 이로 하여금 생각을 해보도록 만든다.

율리아나 아브제예바

쇼스타코비치 24개의 전주곡과 푸가

1950년 바흐의 서거 200주년을 기념하며, 소련은 바흐의 이름을 딴 독일 라이프치히의 콩쿠르에 일류 작곡가를 심사위원으로 보냈다. 2년간 스탈린주의자들의 공격을 견뎌온 쇼스타코비치는 진퇴양난에 빠졌다. ‘형식주의’를 들며 그를 맹비난하고 자유를 위협하던 체제가 이젠 점령국에 문화 사절로 보낸 것이다. 그는 적의를 품은 아첨꾼으로 비칠 게 뻔했다.

1950년 바흐의 서거 200주년을 기념하며, 소련은 바흐의 이름을 딴 독일 라이프치히의 콩쿠르에 일류 작곡가를 심사위원으로 보냈다. 2년간 스탈린주의자들의 공격을 견뎌온 쇼스타코비치는 진퇴양난에 빠졌다. ‘형식주의’를 들며 그를 맹비난하고 자유를 위협하던 체제가 이젠 점령국에 문화 사절로 보낸 것이다. 그는 적의를 품은 아첨꾼으로 비칠 게 뻔했다.

무슨 말을 해야 할지, 어찌할 바를 모르던 쇼스타코비치는 러시아인 피아니스트 타티아나 니콜라예바에게 집중했는데, 그녀는 후에 실력과 관계없이 바흐 콩쿠르에서 우승했다. 니콜라예바의 바흐 연주의 어느 지점은 쇼스타코비치에게 흥미와 영감을 주었다. 이에 그는 바흐를 위시한 ‘24개의 전주곡과 푸가’를 작곡하여 니콜라예바에게 헌정했고, 그녀는 1952년 12월 레닌그라드에서 이를 연주했다. 소련 평론가들은 ‘사회주의적 내용’이 빠졌다며 비난했고, 서구 평론가들은 아예 이 곡을 못 본 체했다.

40여 년이 흐른 뒤, 니콜라예바는 영국 런던에서 전곡을 연주했고, 이를 햄스테드의 한 예배당에서 녹음하여 새로 설립된 하이페리온(Hyperion) 음반사를 통해 발매했다. 다부진 체격의 그녀가 웃음기 없이 강도 높은 집중력을 발휘한 연주에 객석은 숨이 막혔다. 그 이후에 이어진 모든 공연은 니콜라예바의 연주를 기준으로 평가되었고, 모조리 불합격이었다.

그런데 이제 상당한 수준을 감히 선보이는 한 피아니스트 덕분에 포스트-니콜라예바 시대에 진입했다는 사실을 전하게 되어 마음이 놓인다. 2010년 폴란드 바르샤바 쇼팽 콩쿠르 우승자 율리아나 아브제예바(1985~)는 이 기념비적인 작품을 손쉽게 연주해 낸다. 그녀의 접근법은 고매하거나 원칙적이라기보다는 허물이 없다. 아브제예바는 음악 속에서 수수께끼를 찾아내고 이를 청자가 풀도록 내버려둔다. 어떤 곡은 1분이 채 안 되며, 긴 곡은 7분을 넘기지만, 한 곡이 끝나면 그녀는 새로 고침 버튼을 누르고 새로운 수수께끼와 함께 우리 앞에 등장한다. 세 번째 전주곡은 레퀴엠의 기색을 드러내고, 여덟 번째 푸가는 울적한 f#단조로 생일 축하 노래를 비튼다. 한번 들어보라.

나는 충실하기도, 완벽하기도 거부하는 아브제예바의 접근법을 좋아한다. 니콜라예바의 권위는 항상 존경할 것이나, 행복을 위해서라면 이 앨범을 선택하겠다. 여러분도 마찬가지일 것이다.

PERFORMANCE INFORMATION

율리아나 아브제예바 피아노 독주회

9월 21일 오후 5시 예술의전당 콘서트홀

쇼스타코비치 24개의 전주곡과 푸가, 쇼팽 24개의 전주곡

미로슬라브 바인하우어

알로이스 하바 피아노곡 전집

아르놀트 쇤베르크가 무조음악에 질려 음렬주의로 넘어갈 무렵, 체코의 어느 무명 작곡가는 미분음에 미래가 있다고 결정했다. 1차 대전 당시 오스트리아군 소속이었던 알로이스 하바(1893~1973)는 사분음(반음을 다시 반으로 쪼갠 음)으로 조율한 두 대의 피아노를 위한 푸가 세 곡으로 자신의 운을 시험해 보았다. 누구도 차이를 인식할 수 없었고, 지구는 여전히 돌았다.

아르놀트 쇤베르크가 무조음악에 질려 음렬주의로 넘어갈 무렵, 체코의 어느 무명 작곡가는 미분음에 미래가 있다고 결정했다. 1차 대전 당시 오스트리아군 소속이었던 알로이스 하바(1893~1973)는 사분음(반음을 다시 반으로 쪼갠 음)으로 조율한 두 대의 피아노를 위한 푸가 세 곡으로 자신의 운을 시험해 보았다. 누구도 차이를 인식할 수 없었고, 지구는 여전히 돌았다.

이후 공산당에 가입한 하바는 한스 아이슬러와 어울리며 매사에 호기심이 넘쳤던 페루초 부소니와 육분음 작곡을 시도했다. 그는 현악 4중주 몇 곡을 쓰고, 미분음악을 위한 피아노를 새로 설계하고, 등장인물 그 누구도 정확하게 부를 수 없는 사분음 오페라 ‘어머니(Matka)’를 1931년 초연했다. 나치로부터 금지당한 그는 전후 공산당 정권의 그 누구도 자신의 실험을 지지하지 않는다는 사실에 실망했고, 거의 잊혀진 채 1973년 눈을 감았다.

이러한 점에서 미로슬라브 바인하우어(1993~)가 그의 피아노곡 앨범을 냈다는 사실은 어떤 계시이자 예측불허의 농담 같다. 두 장의 CD 중 첫 장은 완성보다는 가능성으로 가득한 피아노 소나타 두 곡을 포함하여 작곡가의 20대 시절인 1914~1919년에 쓰인 곡으로 채워졌다. 놀랄만한 곡은 없다.

재밌는 부분은 1920년대의 곡들이다. 하바의 이지적인 외모 뒤에는 장난기가 숨어있었다. 1920년 작곡된 ‘피아노를 위한 여섯 개의 작품’ 중 네 번째 곡은 동요 ‘1-2-3-4-5, 물고기를 잡아요(1-2-3-4-5, Once I Caught a Fish Alive)’의 곡조다. 1921년 작곡된 왈츠 두 곡은 말하자면 라벨보다 암울하다. ‘피아노를 위한 네 개의 현대적 무곡’은 블루스와 탱고를 조금씩 섞었는데, 쿠르트 바일이 아스토르 피아졸라를 만난 격이다. 이 곡들은 연주하기엔 끔찍이 어렵지만 귀에는 꽤 쉽게 박힌다. 오프톤(조율이 틀어진 톤)의 무곡에 한번 발을 내딛으면, 그 황당함에 폭소가 터지며 차원이 다른 음향의 세계로 이동하게 된다. 이 피아노들이 재조율된 적은 없다고 확신한다. 바인하우어는 실로 대단한 피아니스트다. 꼭 들어보자.

번역 evener

Yunchan Lim: Tchaikovsky, The Seasons

When a major artist performs third-rate music, it’s either going to be a trifling act of self-indulgence or a stunning revelation. It took me three listenings to work out which this was.

Tchaikovsky wrote 12 piano pieces for each month of the year for publication in serial issues of a St Petersburg magazine. The editor appended a poem to each piece without the composer’s involvement. That much is verified fact. Now Yunchan Lim, in a sleeve-note, comes up with a fable relating how the suite describes the last year of a man’s life, a gradual letting-go. Tchaikovsky, who was in the thick of composing Swan Lake at the time, had almost two decades still to live and no pressing thoughts of mortality. I am uncomfortable with the Korean pianist’s false narrative.

And what of the musical interpretation? Yunchan Lim, winner of the 2022 Van Cliburn competition, is the most fascinating, ethereal pianist to emerge in more than a decade. So far, he has not put a finger wrong in recordings of Rachmaninov and Chopin.

In the January segment of The Seasons he veers close to the edge of kitsch, but that’s Tchaikovsky’s fault more than his. In March he offers playing of weightless wonder, a feather on melting snow. June is somewhere between hope and gloom. August is a helter-skelter scamper, a flight from something, possibly reason. October is a soaring cloud of genius, Rachmaninoff’s favourite encore. The last two months deliver a resolution, no entirely convincing.

Yunchan’s playing, dazzling at times, is at odds with his verbal imagination. On third hearing, his performance is deeply satisfying, unconnected to any agenda. You won’t be disappointed.

Schubert: Piano sonata D959, Moments Musicaux

So commanding was Alfred Brendel in Schubert’s piano music that other pianists complain they can’t get him out of their fingers. It’s two decades or more since Brendel last recorded late Schubert, and half century since he made those epochal recordings in Philips, yet his shadow stretches long and no clear contender has since emerged as the Schubert pianist of our time.

Steven Osborne can credibly claim to lead the field. A Scot with a strong record in Beethoven, he disdains Brendel’s emotional neutrality at the opening of Schubert’s penultimate sonata and imposes a convincing interpretation of assertive clarity. The virility of the opening movement is counterpointed by a tenderness in the second that veers daringly towards self-pity before pulling back to moderate pathos. Playfulness returns in the later sections. Osborne leaves us in no doubt that, contrary to much academic speculation, these are not deathbed musings. On the contrary, Schubert seems to be pushing into Beethoven territory, leaving the last sonatas irresolute and still teeming with ambition.

In the Moments Musicaux Osborn is marginally less coherent. The Viennese mordancy that Brendel trademark is much less evident, at least until the sixth Moment when Osborne turns perceptibly inward and plays with deep contemplation, as if to himself. One has a sense of an artist looking for personal answers in a piece of music, always a rewarding auditory experience. Osborne goes beyond past cliches and makes the listener think.

Dmitri Shostakovich: 24 Preludes and Fugues (Pentatone)

For the bicentenary of Johann Sebastian Bach’s death, the Soviets sent their top composer to Leipzig to judge a competition in Bach’s name. Having endured Stalinist attacks for two years, Dmitri Shostakovich was caught between a rock and a hard place. A system that denounced him for ‘formalism’ and threatened his freedom was now sending him as a cultural ambassador to a country under occupation where he would be viewed with hostility masked in sycophancy.

Not knowing what to say, where to turn, he focussed on Tatiana Nikolaeva, a Russian pianist in the Bach competition who was declared the winner, regardless of merit. Something in the way Nikolaeva played Bach appealed to Shostakovich and gave him an idea. He composed 24 Preludes and Fugues – in Bach’s footsteps – and gave them to Nikolaeva to perform in Leningrad in December 1952. Soviet critics complained of a lack of ‘socialist content’. Western critics ignored the set.

Almost forty years later, Nikolaeva performed the set in London and recorded it for the new Hyperion label in a Hampstead chapel. Thick-set and unsmiling, Nikolaeva performed with a depth of concentration that left her listeners breathless. Every subsequent performance has been judged against hers and found wanting.

So it is a relief to report that we have entered a post-Nikolaeva era where a pianist dares to offer a quality of difference. Yulianna Adveeva, Russian winner of the 2010 Chopin competition in Warsaw, brings a light touch to the monumental work. Her approach is conversational rather than worshipful or pedagogic. She finds riddles in the music, leaving them for the listener to resolve. No sooner is one episode over – some are less than a minute, the longest over seven – than she hits the refresh button and confronts us with a fresh conundrum. The third prelude reveals a hint of Requiem, the eighth fugue a twist of Happy Birthday in F# minor with a sombre mood. Go figure.

I like Andreeva’s approach, her refusal to take dictation or be definitive. I will always respect Nikolaeva’s authority, but if I want to wear a happier face, I’ll go for this set. And so should you.

Alois Haba: Complete piano music (Supraphon)

Around the time Arnold Schoenberg got fed up with atonality and moved to serialism, a Czech composer of no renown decided that the future lay in microtones. A soldier in the Austrian army in the first world war, Haba tried his luck with three fugues for two pianos, tuned a quarter-tone apart. Hardly anyone could hear the difference and the world continued to revolve on its axis.

Haba joined the Communist party, palled up with Hanns Eisler and was encouraged to attempt composing in one-sixth of a tone by the ever-curious Ferrucio Busoni. Haba composed a few string quartets, redesigned pianos to play in fractured tones and put on a 1931 quarter-tone opera, Matka, that no-one could sing with any degree of accuracy. Banned by the Nazis he was dismayed to find that the post-war Communist regime had no sympathy for his experiments; he died in 1973, almost entirely forgotten.

Which makes the release of his piano music by Miroslav Beinhauer something of a revelation and, unexpectedly, really good fun. The first of two CDs is filled with music written in his twenties, between 1914 and 1919, including two piano sonatas of more promise than fulfilment. Nothing here to frighten the horses.

It’s the 1920s where the fun begins. Behind Haba’s cerebral exterior lurks mischief. The fourth of six pieces for piano, dated 1920, is a setting of the nursery rhyme ‘1-2-3-4-5, once I caught a fish alive’. Two waltzes of 1921 are, if possible, bleaker than Ravel’s. Dances for piano add a splash of blues and tango. Think Kurt Weill meets Astor Piazzolla. These pieces, brutally difficult to play, enter the ear with surprising ease. Tap your foot to off-tone dances and you’ll be whisked into an altogether other sound world (with a bit of a grin about the absurdity of it all). None of these pianos has been retuned, we are assured. Miroslav Beinhauer is quite some pianist. Really needs to be heard.

글 노먼 레브레히트 영국의 음악·문화 평론가이자 소설가. ‘텔레그래프’지, ‘스탠더즈’지 등 여러 매체에 기고해왔으며, 지금 이 순간에도 자신의 블로그(www.slippedisc.com)를 통해 음악계 뉴스를 발 빠르게 전한다