노먼레브레히트 | SINCE 2012

영국의 평론가가 보내온 세계 음악계 동향

불투명한 런던 공연장의 미래

이대로 가면 런던의 오케스트라들이 사라지고 만다

퀸엘리자베스홀과 퍼셀룸을 운영 중인 사우스뱅크 센터 ©Pete Woodhead

슬프게도, 영국 런던이 더는 음악의 중심이 아니라는 것은 널리 알려진 사실이다. 연간 1~2회씩 런던을 거쳐 순방하던 세계적인 오케스트라들은 더 이상 런던에 체류하지 않는다. 정상급 아티스트들 역시 프랑스의 파리, 독일의 베를린에 주요 공연을 잡는다. 새로운 음악은 씨가 말랐고, 팬데믹 이전부터 세계 초연작은 없었다. 런던은 음악계 지도에서 밀려나고, 추락하고, 곤두박질치는 중이다.

이러한 쇠락에는 브렉시트, 코로나19, 러시아-우크라이나 전쟁, 경제 위기와 더불어 수도에서 자금을 약탈하여 지방에 흩뿌리는 정부의 행보가 있다. 그러나 유치원 수준을 겨우 넘는 적절치 못한 소수 스타트업 단체에게는 우호적이면서 런던의 악단에겐 부당한 처사를 일삼는 정부 외에도 다양한 이유와 변명이 따라붙는다.

이 모든 항목이 침체 원인에 기여한 것은 맞으나, 이 항목들을 쌓는 것만으로는 런던의 음악을 사상 최하로 격하시킨 국가적인 목표 상실과 근본적인 무능을 설명할 수 없다. 경제는 이와 아무런 상관이 없다. 런던은 1930년대 대공황 시기에 두 개의 교향악단을 창단했고, 아르투로 토스카니니로부터 이 오케스트라들이 최고의 반열에 들었다는 놀라운 지지를 받으며 그 음악적 위상을 공고히 했다. 그리고 오늘날, 최고의 마에스트로들은 런던을 기피하고 런던의 교향악단 중 한 곳은 해체를 코앞에 두고 있다.

로열페스티벌홀

경영이 부재하다 싶을 정도의 상황

어쩌다 상황이 이렇게 악화했는지 궁금하다고? 물리적인 환경에서부터 설명을 시작해 보겠다. 런던의 주요 대공연장은 1951년 이래로 템스강변의 로열페스티벌홀이었다. 이곳엔 두 개의 소공연장인 퀸엘리자베스홀과 퍼셀룸이 증축됐으며, 사우스뱅크 센터에서 운영 중이다. 음향 시설이 최고라고는 할 수 없지만, 로열페스티벌홀의 음향에는 의회나 웨스트민스터 사원에 들어설 때 받는 일종의 고양감, 그 특유의 영예로운 기운이 있었다.

지금은 아니다. 그곳에 어떻게 입장하든지 패스트푸드 냄새와 술집에서 나오는 레코드음악의 시끄러운 소리가 당신을 먼저 둘러싼다. 그 후엔 마약, 술, 타락에 찌든 사우스뱅크 센터의 인파로부터 벗어날 수 없다. 가혹한 표현이라고? 절대 그렇지 않다. 공연이 끝난 뒤 관객은 주변의 소음으로부터 오염되지 않은 청각적 경험을 운반해 갈 권리가 있다. 사우스뱅크 센터에는 더 이상 그러한 권리가 존재하지 않으며, 이 공간은 클래식 음악에 대한 무관심을 크게 숨기려 하지도 않는다. 사우스뱅크 센터 회장 미산 해리먼(1977~)은 자신을 ‘사진가·크리에이티브 디렉터·문화 해설자·영국 보그 커버를 장식한 최초의 흑인’이라 설명한다. 이 설명이 현재 사우스뱅크 센터가 추구하는 문화적 가치의 정점이다.

사석에서 해리먼은 클래식 음악을 ‘엘리트주의적’이며 ‘멋지지 않다’고 설명한다. 사우스뱅크 센터는 상주 오케스트라인 런던 필하모닉, 필하모니아를 마치 원치 않는 세입자처럼 대한다. 다음 시즌부터 두 단체의 연간 공연은 35회에서 25회로 감축됐고, 기업 콘퍼런스나 영화 시사회로 더 많은 수익을 내기 위해 최후의 순간까지 버티고 있는 매니저들로 인해 정확한 공연 날짜도 정해지지 않았다. 이들 오케스트라는 절망 속에 빠져 있다. 그 누구도 상관하지 않지만.

런던의 또 다른 대공연장인 바비칸 센터의 음향은 꽉 막혀 있어 새로운 공연장을 지어달라는 수석지휘자 사이먼 래틀의 요구를 시티 오브 런던 법인이 동의할 정도였으나, 비용 확인 후 이 결정은 철회되었다. 래틀은 열악한 조건을 견디기 어려웠는지, 계약 도중 뮌헨으로 달아났다. 재능과 야심이 넘치는 대부분의 영국인 지휘자는 이제 섬 밖에서 미래를 찾고 있다. 로열 앨버트홀의 경우 한여름에는 BBC 프롬스를, 다른 계절에는 로열 필하모닉 오케스트라를 무대에 올린다. 오케스트라를 잠시 폐지하겠다고 위협했던 BBC의 예산 삭감으로, 작년과 올해의 BBC 프롬스는 상당히 절제됐다. 앨버트홀은 중년의 록 스타와 관객이 돌아와 그들의 영광스러웠던 과거를 휘황찬란한 의상으로 되새길 때에야 진가를 발휘한다. 클래식 음악 공연의 관객은 그에 비해 초라해 보인다.

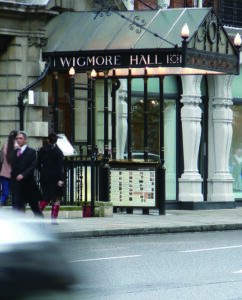

위그모어홀

스스로 해결을 찾아 나서야 하지 않나?

런던에서 침체하지 않은 뛰어난 클래식 음악 명소로는 옥스퍼드 스트리트 뒤쪽 위그모어홀과 유로스타 터미널 뒤쪽의 킹스 플레이스만 남았다. 두 곳 모두 주로 충실한 중산층 관객으로부터 지원받으며 타협 없이 훌륭한 기준을 유지하고 있다. 위그모어홀은 바리톤 마티아스 괴르네와 소프라노 아스믹 그리고리안의 가곡 사이클, 다닐 트리포노프와 미츠코 우치다의 피아노 리사이틀, 에벤 콰르텟과 카살스 콰르텟을 무대에 올리니, 가히 세계 최고라 볼 수 있다. 킹스 플레이스는 주요 작곡가에 집중한 공연을 주말 내내 선보인다. 이 두 곳은 영광스러웠던 나날의 유산이다.

일부는 클래식 음악의 쇠락이 붕괴하는 의료 서비스, 파업에 시달리는 열차, 무너져 내리는 교육 환경, 국가에 대한 일반적인 불만 등 폭넓은 사회 문제의 핵심이라 주장한다. 낙관론자들은 내년 총선과 정권 교체로 문제를 바로잡을 수 있다고 상상하지만, 그럴 리 없다. 관현악이 정치적 우선순위에 오를 일은 결코 존재하지 않는다. 음악계가 마주한 재난의 소용돌이를 뒤집으려면 자기 손으로 고삐를 쥐어야 한다.

영국의 예술 공공자금은 1945년 경제학자 존 메이너드 케인스(1883~ 1946)가 소량의 보조금으로 국가적인 창의력 재건을 위해 고안했다. 영국 예술위원회가 맨 처음 런던 심포니에 승인한 보조금은 2,000파운드였다. 현재 런던심포니는 200만 파운드를 받지만, 여전히 부족함을 호소한다. 의존성 문화에 기대며 지낸 지 거의 80여 년이 흐른 지금, 음악계는 다른 곡조를 찾아야만 한다.

런던은 전 세계 사업이 몰려드는 곳이다. 그 런던의 문화적 시설이 무너져 내리고 있다. 사우스뱅크 센터는 근무 시간을 주 4일 제도로 줄였다. 만약 사우스뱅크 센터가 파산한다면(파산할 만하다) 런던의 예술 존립은 어려워질 것이고, 관련 사업은 파리와 베를린에 돌아갈 것이다. 도시 중심에 관현악이 사라진 런던은 해가 진 루마니아의 부쿠레슈티, 핀란드의 헬싱키보다도 볼 것이 없어진다. 심판의 순간이 머지않았다. 일부 시민들이 여름휴가 이후 조처를 준비 중이라고 들었다. 계속 귀를 열어 두도록 하자. 번역 evener

노먼 레브레히트 칼럼의 영어 원문을 함께 제공합니다

본 원고는 본지의 편집 방향과 일치하지 않을 수 있습니다

It is a sad truth, widely acknowledged, that London is no longer a music capital. World orchestras that passed through once or twice a year no longer stop over. Headline artists save their signature concerts for Paris and Berlin. New music has dried up. There hasn’t been a premiere of world consequence since before Covid. London is falling, falling, falling off the music map.

Various reasons and excuses are attached to this decline, among them Brexit, Covid, the Ukraine war, economic woes and a government that is plundering funds from the capital and spreading it around the regions, going out of its way to penalize London orchestras while smiling upon pointless little minority start-ups that are barely above kindergarten level.

These are all contributory causes but the cumulation of factors does not begin to describe the loss of national purpose and fundamental incompetence that has relegated music in London to an all-time low. The economy has nothing to do with it. London achieved its musical status in the 1930s, during the Great Depression, adding two new symphony orchestras and drawing a surprised endorsement from Arturo Toscanini that they ranked among the best. Today, star maestros shun London and one of its symphony orchestra came within a matter of days of being abolished.

You want to know how bad it has got? Let me start with the physical surroundings. London’s main symphonic venue since 1951 has been the Royal Festival Hall beside the river Thames, augmented by two smaller halls, the QEH and Purcell Room, and run by a South Bank Board. Acoustics were never first-rate but the Festival Hall had an aura of embedded glory, the kind of uplift one gets on entering Parliament or Westminster Abbey.

No longer. Approaching from any direction you are beset by a stink of fast food, a racket of canned music from pubs and bars and a throng of people who hang out on the South Bank for drugs, drink and degradation. Am I too harsh? Not much. After a concert you have a right to carry away the aural experience unpolluted by ambient noise. That right no longer exists on the South Bank, nor does the site make much secret of its disinterest in classical music. Its chairman, Misan Harriman, is by his own description a ‘photographer, creative director and cultural commentator, and is the first Black person in the history of British Vogue to shoot the cover of its September issue.’ Such are the present summits of South Bank cultural values.

Harriman, in private conversations, has described classical music as ‘elitist’ and ‘not cool’. The South Bank treats its resident orchestras – the London Philharmonic and Philharmonia – like unwanted tenants. Both have been cut from 35 concerts a year to 25 next season and neither has been given fixed dates, with managers holding out until the last minute in the hope of obtaining more lucrative bookings for business conferences and film premieres. The orchestras are in despair. No-one cares.

London’s other symphonic venue, the Barbican, has an acoustic so constipated that the City of London Corporation agreed to Simon Rattle’s demand to build a new hall, only to retract when they saw the cost. Rattle, unwilling to endure inferior conditions, fled to Munich in mid-contract. Most British conductors of talent and ambition now seek their futures abroad.

The Royal Albert Hall stages the BBC Proms in midsummer and the Royal Philharmonic Orchestra at other times. The Proms, last year and this, are seriously low-key as a result of BBC cuts, which briefly threatened to abolish an orchestra. The Albert Hall comes into its own with middle-aged rock stars when the public dresses up in sparkly outfits to relive a glamourous past, Audiences at classical concerts look shabby by comparison.

The only classical attractions in London that are free of gloom are the chamber music venues at the Wigmore Hall, behind Oxford Street, and Kings Place, behind the Eurostar terminal. Both maintain a standard of uncompromising excellence, funded largely by a loyal middle-class audience. The Wigmore puts on Lieder cycles by Mathias Goerne and Asmik Grigoryan, piano recitals by Daniil Trifonov and Mitsuko Uchida, string quartets by the Ebène and the Casals: the world’s best. Kings Place does weekend-long immersions in major composers. These are the relics of our glory days.

Some claim that classical decline is part and parcel of a wider malaise: a collapsing health service, strikebound trains, a sinking education system and general national dissatisfaction. Optimists imagine that a general election and a change of Government will put things to rights next year. It won’t. Orchestral music will never be a political priority. If music is ever to reverse its spiral of disaster, it will need to take governance into its own hands.

The public funding of British arts was invented in 1945 by the economist John Maynard Keynes with a view to regenerating national creativity with small subsidies. The first Arts Council grant to the London Symphony Orchestra was £2,000; today the LSO receives £2 million and still pleads poverty. After almost eighty years of dependency culture, music must come up with a different tune.

London is where the world comes to do business. Its cultural amenities are collapsing. The South Bank has cut its working week to four days. If it goes bust, as it deserves to, arts will be hard to locate and the business classes will divert to Paris and Berlin. Without orchestral music at its core, London will have less to offer after dark than Bucharest and Helsinki. A moment of reckoning is near. I hear that some citizens are preparing to take action after the summer break. Watch this space.

글 노먼 레브레히트

영국의 음악·문화 평론가이자 소설가. ‘텔레그래프’지, ‘스탠더즈’지 등 여러 매체에 기고해왔으며, 지금 이 순간에도 자신의 블로그(www.slippedisc.com)를 통해 음악계 뉴스를 발 빠르게 전한다