노먼 레브레히트 칼럼 | SINCE 2012

영국의 평론가가 보내온 세계 음악계 동향

2024년을 빛낸 음악

영국 평론가가 추천한 화제의 음반들

➊시벨리우스 바이올린 협주곡 외 Decca 4854748

지난해는 대형 레이블에겐 예년과 비슷했지만, 소형 레이블에겐 불안 가득한 한 해였다. 독립 레이블 네 곳의 인수가 있었는데, 하이페리온이 유니버설 뮤직에, BIS가 애플에, 챈도스가 낙소스에, 디바인 아트가 로즈브룩에 넘어갔다. 수십 년 만에 보는 대규모 정리로 인해 각 레이블이 본연의 완강한 개성을 앞으로 10년은 유지할 수 있을지 사람들의 궁금증을 자아냈다.

2024년의 음반을 고르며 시대를 정의하고 미래의 기준도 통과할 작품을 찾아보았다. 재닌 얀센의 시벨리우스 협주곡과 프로코피예프 협주곡 1번이 담긴 음반(Decca)➊은 전설에 비할만한 녹음이라고 할 수 있다. 윤디의 모차르트 피아노 작품(Warner Classics)➋은 독특하여 다신 반복되지 않을 해석이었다. 반면, 클라우스 메켈레의 쇼스타코비치 교향곡 데뷔 음반(Decca)➌은 건강에 해가 될 정도로 상당히 조리가 덜 되었다.

주목할 만한 소형 레이블의 음반으로는 바이올리니스트 기돈 크레머가 평생의 음악을 선보인 ‘운명의 노래’(ECM)➍가 있다. 76세의 크레머는 폴란드계 러시아 작곡가 미에치스와프 바인베르크(1919~1996)와 발트해 작곡가를 섞어, 소련의 사상 통제 역사를 얼어붙은 바다 위로 살랑이던 독립의 소리에 이어냈다. 지난해 2월, 나는 이 음반 리뷰에 이렇게 적었다. “동료 대부분이 지휘로 돌아선 지 오래인 나이에 바이올린을 연주하는 크레머의 헌신은 그가 악기를 얼마나 밀접하게 자신의 목소리로 여기는지를 보여준다. 수십 년간 그의 음색은 모스크바식 정밀주의에서 모든 것을 포용하는 둥근 따뜻함으로 부드러워졌다. 이 꾸밈없고 희망적인 음반은 인류애와 이상주의로 가득 차 있다. 신보를 완벽하다고 추천해 본 적이 없지만, 이 음반은 추천한다.”

찬사가 필요한 비올라

➎ 요크 보엔: 비올라 협주곡 외 SWR music SWR19158CD

나를 고쳐 앉게 하고 때론 마음까지 돌리게 한 소형 레이블 음반은 더 있다. SWR 뮤직의 비올라 협주곡 한 쌍이 담긴 이 음반➎이 그렇다. 비올라는 공연장 레퍼토리로는 부당한 취급을 받는데, 바이올린 협주곡의 경우 자주 연주되는 곡이 50곡, 첼로와 오케스트라의 경우 대여섯 곡이라면, 비올라는 아르놀트부터 버르토크, 슈니트케, 존 윌리엄스에 이르는 일부 훌륭한 작곡가의 비올라 협주곡이 분명 존재하는데도 불구하고 공연되는 작품이 하나도 없다.

그런 의미에서 이 음반은 귀를 열어준다. 랄프 본 윌리엄스보다 살짝 후배 세대인 요크 보엔(1884~1961)은 영국 음악 르네상스 시기인 19세기 후반부터 20세기 초반 역사에 그다지 조명되지 않았다. 비올라 연주 비르투오소인 라이어널 테르티스(1876~1975)를 위해 작곡한 그의 비올라 협주곡은 1908년 명쾌한 초연을 마치고 이어진 미국 공연에서도 호평받았으나, 그 뒤로 80여 년간 침묵 속에 잠들었다. 베를린필 비올라 수석 디양 메이의 이번 연주는 선율과 감상적인 유혹으로 가득 찬 초콜릿 상자 같다. 응접실에서의 느릿한 춤사위 같은 순간이 할리우드 카우보이 영화라고 착각할 만한 순간과 어우러지는 작품이다. 음악은 지나치게 진지한 경우가 없어 청자에게 사뿐히 다가오며, 디양 메이는 롤러스케이트를 탄 하이페츠처럼 연주한다.

마찬가지로 테르티스를 위해 1929년 작곡된 윌리엄 월턴(1902~1983)의 비올라 협주곡은 작곡가의 초기 작품으로, 테르티스는 “지나치게 현대적”이라고 평했고, 파울 힌데미트가 초연했다. 영국 전원의 소중한 시간을 내포하여 시대적 불안은 찾아볼 수 없지만, 하이페츠를 위한 바이올린 협주곡이나 피아티고르스키를 위한 첼로 협주곡을 작곡하고 남은 자투리라고 볼 수는 없다. 피날레의 거대한 바순 선율만을 위해서라도 한번 들어볼 만하다. 전 베를린필 비올리스트 브렛 딘이 훌륭한 도이치 방송교향악단을 넘치는 영향력으로 지휘했다. 비올라는 더 많은 찬사를 받아 마땅하다.

냉소를 품은, 진보적인 녹음

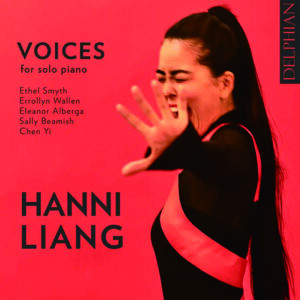

➏ ‘피아노 독주를 위한 목소리’ Delphian DCD34326

다음으로는 에설 스마이스(1858~1944)의 피아노 소나타 2번이 담긴 음반(Delphian)➏을 소개한다. 토머스 비첨과 다른 찬미자들에 따르면 영국 중산층 군인 가정에서 자란 부치 레즈비언(여성 동성애에서 상대를 리드하는 쪽)인 스마이스는 서프러제트(참정권 운동)로 복역 당시 홀로웨이 교도소에서 동료 제소자들을 칫솔로 지휘한 적도 있다. 버지니아 울프는 에설에게 사랑받는 것을 두고 “거대한 게에게 잡힌 느낌”이라고 말한 바 있는데, 이러한 에설의 가공할 만한 신체는 자신의 음악에 존재하는 가치를 가로막았다.

글라인드본이 최근 다시 올린 에설의 오페라 ‘난파선 약탈자들’은 부흥하고 있다. 독일의 일부 오페라 하우스도 이 바통을 이어받았다. 이외에도 또 뭐가 있을까?

이 피아노 소나타 2번 c단조를 들어보라. 1877년 오페레타 가수를 향한 번뜩이는 열정 속에서 작곡된 이 곡은 슈만과 브람스의 중간에 위치하나, 예측에 반항하고 삐죽한 개성을 표현하여 강력한 존재감을 내뿜는다. 당시 에설은 독일 라이프치히에서 공부하는 19세 학생이었다. 그 무엇보다 ‘소나타’라 할 수 있는 이 작품에서 흘러나오는 장래성은 감탄을 자아낸다.

그로부터 1년 뒤 작곡된 ‘(매우 암울한 자연) 주제에 의한 변주곡’ D장조는 에설이 자신의 정체성을 필요 이상으로 심각하게 받아들이지 않았다는 것을 말해준다. 치기와 솜씨가 넘치는 이 20분짜리 모음곡은 에설 본인이 알던 그리그, 차이콥스키 등의 무리에 단호하게 면박을 준다. 음울하다기보다는 퉁명스럽고, 저녁 식사 자리의 배 나온 셔츠 자락을 비웃는 듯하다.

여기서 독일 뮌헨 아카데미의 강사이자 피아니스트인 한니 리앙의 신념이 빛난다. 스마이스의 작품 사이를 오가며 그는 네 곡의 현대작품 연주하는데, 그중 샐리 비미쉬(1956~)의 ‘밤의 춤’이 놀라울 정도로 인상적이다. 에롤린 월렌(1956~), 첸 이(1953~), 엘리너 알베르가(1949~)가 쓴 다른 곡들은 좀 더 독특하며, 단 하나의 지루한 구절도 허락하지 않았다. 참고로 델피안은 영국 에든버러의 인디 레이블로, 이는 워너 클래식스, 소니 클래식스와 같은 다른 ‘노땅’ 레이블들은 전혀 시도하지 못했을 녹음이다.

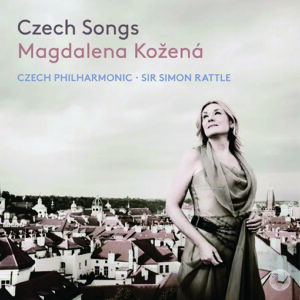

고향의 노래

마지막으로 메조소프라노 막달레나 코제나(1973~)가 고향인 체코 노래를 부른 음반(Pentatone)➐이 있다. 내가 코제나를 처음 접한 것은 1990년대에 발매된 바흐 아리아 음반인데, 녹음 당시 그의 나이는 22세였다. 그 목소리는 밝으면서도 동시에 어두워 마치 존 르 카레(1931~)의 소설에 등장한 에마 커크비(1949~) 같았다. 커크비와 그 동료들이 바로크 음악 대부분을 맡고 있다는 점을 고려했을 때 체코 브르노 출신의 무명 가수는 갈 곳을 찾기 어려웠을 것이다. 코제나는 빈 폴크스오퍼에서 인턴으로 한 해를 보냈는데, 이는 관습적인 커리어와는 거리가 아주 멀었다. 현재 50세가 된 코제나는 실황 연주보다는 리코딩 아티스트로 더 잘 알려져 있다. 지휘자 사이먼 래틀과 결혼한 그는 베를린에 거주하며 레퍼토리를 신중히 선택한다.

마지막으로 메조소프라노 막달레나 코제나(1973~)가 고향인 체코 노래를 부른 음반(Pentatone)➐이 있다. 내가 코제나를 처음 접한 것은 1990년대에 발매된 바흐 아리아 음반인데, 녹음 당시 그의 나이는 22세였다. 그 목소리는 밝으면서도 동시에 어두워 마치 존 르 카레(1931~)의 소설에 등장한 에마 커크비(1949~) 같았다. 커크비와 그 동료들이 바로크 음악 대부분을 맡고 있다는 점을 고려했을 때 체코 브르노 출신의 무명 가수는 갈 곳을 찾기 어려웠을 것이다. 코제나는 빈 폴크스오퍼에서 인턴으로 한 해를 보냈는데, 이는 관습적인 커리어와는 거리가 아주 멀었다. 현재 50세가 된 코제나는 실황 연주보다는 리코딩 아티스트로 더 잘 알려져 있다. 지휘자 사이먼 래틀과 결혼한 그는 베를린에 거주하며 레퍼토리를 신중히 선택한다.

코제나의 최신 음반을 들으면 당최 예측할 수 없는 성숙한 음성에 감탄하게 된다. 무거움 속 가벼움, 형형색색 속 어두움으로 음색은 깊어지고 원숙해져, 진지함이 더해진 브리기테 파스밴더(1939~)를 연상케 한다. 음반의 구성을 따라가다 보면 코제나가 야나체크 오페라의 예누파나 카티아가 된 순간을 만나며, 또 다른 지점에서는 거의 쇤베르크나 베르크의 영역에 가닿는다.

코제나가 선택한 곡들은 모두의 예상을 뛰어넘는데, 그중에는 현대에 가장 적게 연주된 위대한 작곡가 보후슬라프 마르티누의 일본 민요 모음곡, 드보르자크의 초기작, 홀로코스트로 살해당한 두 명의 유대인 작곡가 한스 크라사(1899~1944)와 기드온 클라인(1919~1944)의 일부 곡도 있다.

마르티누의 곡은 드뷔시와 라벨이 꾸며낸 가짜 오리엔탈리즘과는 전혀 다르다. 흡사 초밥 안주 없는 체코 플젠 맥주만큼이나 체코답다. 마르티누는 상점 창문 너머로 보았을, 국경을 건너온 타국 문화 위에 소용돌이를 그려 넣는다. 그가 그리는 일본은 순수한 상상이자 환상이고, 코제나는 이를 전적으로 포용한다.

드보르자크의 작품은 브람스의 ‘보헤미안 랩소디’에서 사용했을 법한 목가적인 반복이 이어진다. 한스 크라사의 작품은 단호하게 현대적이기에, 경계를 아는 알반 베르크의 ‘룰루’처럼 느껴진다. 기드온 클라인의 자장가에는 ‘잘자라 내 아가’라는 제목이 히브리어로 붙어 있다.

코제나는 마르티누의 일본, 드보르자크의 모라비아를 거쳐, 경이롭게 보정된 체코 테레친 출신 두 작곡가의 비극적인 역사를 유람한다. 경이와 긴장은 매 순간 자라나고, 래틀이 지휘하는 체코 필하모닉은 나무랄 데 없는 펜타톤의 음색을 직관적으로 유지한다. 지난 한 해 동안 내가 들었던 모든 리사이틀 음반 중 가장 생동하는 음반이다.

번역 evener

노먼 레브레히트 칼럼의 영어 원문을 함께 제공합니다.

본 원고는 본지의 편집 방향과 일치하지 않을 수 있습니다.

2024 has been a flat year for major labels and an unsettled one for minors. Four independent outfits sold out – Hyperion to Universal, Bis to Apple, Chandos to Klaus Heymann, Divine Art to Rosebrook – the biggest shakeout in decades, leaving us wondering how much of their stubborn individuality might survive in the decade ahead.

In choosing the album of the year, I look for projects that define the era and will pass the test of time. Janine Jansens’ recording of the Sibelius and first Prokofiev concertos on Decca, for example, is one that bears comparison with the legends. Yundi Li’s Mozart piano music on Warner is another – a unique and unrepeatable set of interpretations. Klaus Mäkelä’s debut recording of Shostakovich symphonies is so undercooked it might endanger health.

One compelling small-label release is the violinist Gidon Kremer performing the music of his lifetime on an ECM album called Songs of Fate. Kremer, 76, mixes Baltic composers with the Polish-Soviet Mieczyslaw Weinberg, bridging memories of Soviet thought-control and rustlings of independence beside a frozen sea. Reviewing it in February 2024, I wrote: Kremer’s commitment to playing the violin at an age when most colleagues have long turned to conducting shows how closely he regards the instrument as his personal voice. Down the decades, his tone has mellowed from Moscow-tooled precisionism to a round, all-embracing warmth.

This austere and uplifting record is imbued with humanity and idealism. I don’t think I ever recommend a new record as essential. This one is.

But there was more on small labels that made me sit up, and sometimes change my mind. For instance, a pair of viola concertos on SWR Music. The viola gets treated unfairly in concerthall repertoire. There are fifty violin concertos that get regularly played and half a dozen for cello and orchestra. Yet, despite the existence of viola concertos by some very good composers – from Arnold to Bartok, Schnittke to John Williams – not one gets a public airing.

The SWR release is an ear-opener. York Bowen, slightly younger than Ralph Vaughan Williams, took a back-seat in the English musical renaissance. His viola concerto, written for the virtuosic Lionel Tertis, had a cheerful premiere in 1908, followed by a well-received US hearing, and then eight decades of silence. The current performance by Diyang Mei, principal viola of the Berlin Philharmonic, is a chocolate box of melodic and mushy temptations. Moments of drawing-room smooch mingle with what might easily be mistaken for a Hollywood cowboy film. This is music that does not take itself or its listeners over-seriously and Dijang Mei plays it like Heifetz on roller-skates.

Walton’s viola concerto, also written for Tertis, is a fairly early work, dated 1929. Tertis found it ‘too modern’ and Paul Hindemith played the premiere. It has cherishable moments of English pastorality and none of the nervousness of its period; but it’s not a patch on the violin concerto that Walton would write for Heifetz, or the cello concerto for Piatigorsky. Still, it’s well worth a spin, if only for the big bassoon tune in the finale. Brett Dean, himself an ex-Berlin Phil violist, conducts the excellent Deutsche Philharmonie with infectious proselytism. The viola needs all the shout-outs it can get.

And then we have Ethel Smyth’s second piano sonata on Delphian. Smyth was a middle-class butch lesbian from a military family who went to jail for the Suffragette cause and was seen conducting fellow-inmates at Holloway Prison with a toothbrush. That, in sum, is the impression given by Thomas Beecham and other admirers. Virginia Woolf said being loved by Ethel was ‘like being caught by a giant crab’. Her daunting physicality occluded whatever merit there was in her music.

Glyndebourne’s recent revival of her opera The Wreckers has been restorative and several German opera houses have taken it up. So what else is there to discover?

Try the second piano sonata in C minor. Composed in 1877 in a flush of passion for an operetta singer, the sonata inhabits a patch midway between Schumann and Brahms but with a strong enough presence to defy prediction and express a spiky individuality. Smyth was 19 at the time, a student in Leipzig. The promise is there for all to hear. This is quite some sonata.

A set of variations in D major on ‘An Original Theme (of an Exceeding Dismal Nature)’, written a year later, tells us that Smyth took herself no more seriously than necessary. It’s a 20-minute suite of cocky facility that puts the likes of Grieg and Tchaikovsky (whom she knew) firmly in their place. Not dismal at all: more snarky and mocking of the stuffed shirts around the dinner table.

The conviction here is blazed by pianist Hanni Liang, an academy teacher in Munich. Between and around the Smyth works she performs four modernities, of which Sally Beamish’s Night Dances is brilliantly evocative. The other pieces, more quirky, are by Erollyn Wallen, Chen Yi and Eleanor Alberga. Not a dull phrase among them. The Delphian label, by the way, is an Edinburgh indy with a knack for the unexpected. You’d never hear a recital like this on Warner, Sony or the other classical codgers.

Finally, on Pentatone, there was Magdalena Kozena singing songs of her native lands. The first I heard of Kozena was a mid-1990s album of Bach arias, recorded when she was 22. The voice was at once light and dark – think Emma Kirkby in a John Le Carre novel. Given that Kirkby and Co had covered most of the Baroque, it was hard to see where an unknown from Brno would go. Kozena put in an intern year at the Vienna Volksoper and that was as far as she went on the conventional career path. Now 50, Kozena is known more as a recording artist than a live performer. Married to the conductor Sir Simon Rattle, she lives in Berlin and chooses her repertoire with care.

On her latest release, one has to marvel at the unpredictable way a voice matures. From light in weight and dark in colour, the tone has deepened and rounded – think Brigitte Fassbaender with added gravitas. There are moments in this programme where she could be Jenufa or Katya in Janacek’s operas. At other points she is almost in the range of Schoenberg or Berg.

The songs she chooses are unexpected – a set of Japanese songs by Bohuslav Martinu, possibly the least performed great composer of modern times – some juvenilia by Antonin Dvorak and fragments by Hans Krasa and Gidon Klein, two Jewish composers who were murdered in the Nazi Holocaust.

The Martinu songs are nothing like the faux-orientalisms confected by Debussy and Ravel. They are as Czech as Pilsen beer, without a side-order of sushi. Martinu is drawing curlicues on an imported culture that he may have seen through a shop window. His Japan is purely imagined, a fantasy that Kozena embraces to its fullness.

Dvorak’s songs are bucolic jingles of the sort Brahms might have used in his Bohemian Rhapsody. Krasa’s approach is determinedly modern, borderline Lulu. Klein’s lullaby also has a Hebrew title, meaning ‘sleep my son’.

The excursion Kozena takes from Martinu’s Nippon through Dvorak’s Moravia to the tragic histories of two Terezin composers admirably calibrated. Surprise and tension grow throughout the hour. The Czech Philharmonic, Rattle conducting, offer intuitive sustenance in immaculate Pentatone sound. This is the most vivid recital disc I have heard all year.

글 노먼 레브레히트 영국의 음악·문화 평론가이자 소설가. ‘텔레그래프’지, ‘스탠더즈’지 등 여러 매체에 기고해왔으며, 지금 이 순간에도 자신의 블로그(www.slippedisc.com)를 통해 음악계 뉴스를 발 빠르게 전한다