“노먼 레브레히트 칼럼 침묵의 비밀”

침묵의 비밀

클래식 음악계의 불협화음에 맞서는 침묵이라는 무기

우리 시대 지휘자에게 붙은 최악의 칭호는 1980년대 후반 런던의 두 오케스트라가 로열 페스티벌 홀의 단독 계약권을 놓고 치받으며 탄생했다. 두 오케스트라 모두 좋은 모양새는 아니었다. 당시 필하모니아 오케스트라의 지휘자는 연주자들이 이해하기 어려운 생각을 지닌 이탈리아인 정신분석가 주세페 시노폴리(1946~2001)였고, 영감이 넘쳤던 지휘자 클라우스 텐슈테트(1926~1998)를 암으로 잃은 런던 필하모닉의 연주자들은 후임으로 내정된 프란츠 벨저 뫼스트(1960~)라는 이름의 서른 살이 채 안 된 안경잡이 오스트리아인에 불안해했다. 두 악단의 음악가들은 예상대로 프란츠에게 ‘솔직히 평균보다도 못한(Frankly Worse than Most)’이라는 별명을 붙였다. 이는 프란츠뿐만 아니라 마에스트로 전체에 대한 모욕이기도 했다. 꼬리표에 따르면 모든 지휘자는 형편없었고, 그게 무엇을 의미하든 별로 상관없었다.

우리 시대 지휘자에게 붙은 최악의 칭호는 1980년대 후반 런던의 두 오케스트라가 로열 페스티벌 홀의 단독 계약권을 놓고 치받으며 탄생했다. 두 오케스트라 모두 좋은 모양새는 아니었다. 당시 필하모니아 오케스트라의 지휘자는 연주자들이 이해하기 어려운 생각을 지닌 이탈리아인 정신분석가 주세페 시노폴리(1946~2001)였고, 영감이 넘쳤던 지휘자 클라우스 텐슈테트(1926~1998)를 암으로 잃은 런던 필하모닉의 연주자들은 후임으로 내정된 프란츠 벨저 뫼스트(1960~)라는 이름의 서른 살이 채 안 된 안경잡이 오스트리아인에 불안해했다. 두 악단의 음악가들은 예상대로 프란츠에게 ‘솔직히 평균보다도 못한(Frankly Worse than Most)’이라는 별명을 붙였다. 이는 프란츠뿐만 아니라 마에스트로 전체에 대한 모욕이기도 했다. 꼬리표에 따르면 모든 지휘자는 형편없었고, 그게 무엇을 의미하든 별로 상관없었다.

런던 음악계에서 퇴출된 지휘자

그 별명이 등장했던 공연 리뷰는 프란츠의 사직을 권했다. 한편, 그가 떠나면 계약권을 잃을까 두려웠던 런던 필 단원들은 그에게 남아달라고 청했다. 7년 뒤 그가 영원히 런던을 떠나자 한 신랄한 비평가는 이렇게 썼다. “갑자기 등장했던 프란츠가 아무런 성과도 없이 떠난다.”

마찬가지로 런던에서 쫓겨난 시노폴리는 베를린에서 ‘아이다’를 지휘하던 도중 55세의 나이로 세상을 떠났다. 두 오케스트라는 계약권을 나누기로 합의했고 그 이후로도 분쟁은 이어졌다. 이 이야기를 끝까지 다 듣고 나면 클래식 음악계가 어찌나 불쾌할 수 있는지, 그 시큼한 뒷맛만 남는다.

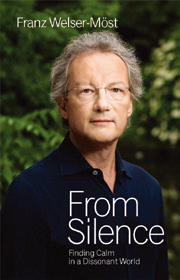

올해로 60세가 된 프란츠 벨저 뫼스트는 회고록 ‘침묵으로부터: 불협화음 속 평온을 찾아서(From Silence: Finding Calm in a Dissonant World)’에서 자신의 고난을 회상한다. 그는 “비열한 행위는 점점 심해지고 오케스트라의 지지는 약화되는 동안, 일부 이해 관계자들에 의해 방패막이로 이용된” 기분이 어떠한지 기술했다. 프란츠가 배운 것은 무엇이었을까? 주변의 소음을 차단하고 “침묵을 믿는 법을 발견”하라고 그는 조언한다.

그 해결책은 프란츠에게 효과가 있었다. 세기가 바뀐 이래로 그는 미국에서 가장 뛰어난 클리블랜드 오케스트라의 음악감독 자리를 맡고 있다. 전 세계에서 가장 경쟁이 치열한 업계에서 그는 명쾌한 음을 유지하며 R. 슈트라우스의 비할 데 없는 화려함과 버르토크의 보기 힘든 섬세함을 정교하게 다듬어 냈다. 클리블랜드에서의 지난 20년으로 그는 자신의 능력을 입증했다. 그의 회고록의 요점은 인생의 갈등을 넘어서 그 자신이 죽기 직전 찾아낸 고요에 집중하는 것이다.

생사의 기로에서 침묵을 발견하다

1978년 11월 19일 슈베르트 서거 150주년 기념일, 공연장으로 향하던 프란츠가 탄 자동차 운전기사가 알프스산맥의 한 도로에서 의식을 잃는다. 그의 옆 좌석에 앉았던 여성은 사망했다. 병원에서 깨어난 당시 18살의 프란츠는 부러진 손가락과 척추로 인해 바이올리니스트로서의 삶이 끝났음을 깨닫는다. 그는 그 사고가 있기 바로 직전, “믿기 어려운 침묵”이 그를 감싸 안았다고 확신한다.

그는 이렇게 기술하고 있다. “저는 완전한 침묵 속에 있었습니다. 앞으로 몇 초 뒤에 일어날 일에 영향을 미치기는커녕 움직일 수조차 없었죠. 이 침묵은 마치 세상의 알려진 모든 규칙을 무시하는 것처럼 보였습니다. 그날 이후로 저는 계속해서 침묵의 현상에 대해 생각했습니다. 음의 부재라는 조건에서의 침묵에 대해서 말이죠.”

음악에서 ‘침묵’의 개념은 미국 작곡가 존 케이지에 의해 설명된 바 있다. 그는 침묵을, 예기치 않은 일이 항상 예상되어야 하는 확률이나 우연한 사건과 연관시켰다. 프란츠 인생의 확률 변수는 안드레아스 폰 베닝젠이라 불렸던 리히텐슈타인 남작이었는데, 어린 시절 빌헬름 푸르트뱅글러(1886~1954)의 무릎 위에서 자란 남작은 그에 필적하는 천재를 찾는 데 일생을 바친 사람이었다. 오스트리아의 도시 벨스(Wels)에서 자신의 이상을 찾아낸 남작은 프란츠 뫼스트의 성을 ‘벨저-뫼스트’로 바꾸고 그를 양자이자 후계자로 입양한다. 의사와 정치인이었던 프란츠의 부모는 아무런 반대도 하지 않았다.

이상하게 들릴 만큼 남작은 확실히 제정신이 아니었다. 프란츠가 남작에게서 벗어났을 무렵, 그의 성은 이미 굳어져 있었고 그는 EMI 레코드의 떠오르는 스타로 부상하고 있었다. 나는 도쿄 외곽의 한 공연장에서 클라우스 텐슈테트를 대신하여 지휘하는 그를 처음 보았는데, 그는 공연 중간 휴식 시간에 속을 게워내고 다시 나와 내 평생 가장 짜릿했던 베토벤 교향곡 5번을 선보였다. 그날 이후로 나는 자기 영감에 관해서는 절대로 그의 능력을 의심하지 않는다.

위대한 지휘력의 바탕은 침묵!

런던에서의 실패로 인해 그는 15년 동안 취리히 오페라에서 젊은 요나스 카우프만을 비롯하여 시계 제작자들 같은 스위스 오케스트라, 수많은 재능 넘치는 앙상블과 일하며 회복의 시간을 보냈다. 어느 여름날 밤, 나는 그가 ‘장미의 기사’ 전주곡을 2배속으로 연주하는 걸 들었다. 이유를 묻자 프란츠는 씩 웃으며 말했다. “할 수 있기 때문이죠. 긴 시즌을 이어왔으니 느슨해질 필요가 있었습니다.”

클리블랜드에서 프란츠는 도시의 유일한 음악평론가의 적개심과 마주하는가 하면 자신의 해고 소송에도 나서 진술했다. 은퇴한 원로 연주자들이 반대를 표명했지만, 그의 재임은 대체로 무난히 이뤄졌고, 엄청난 박탈감에 휩싸인 공업 도시에서의 음악의 질도 탁월했다. 빈 슈타츠오퍼의 음악감독으로 보낸 짧은 기간 외에도 런던을 떠난 이후 그의 전진에는 흔들림이 없었다. 그의 회고록은 “사랑하는 나의 아내, 겔리에게”라는 헌사로 시작한다. 그는 “사색의 침묵 속에 은둔할 수 있는 가능성”을 소중히 여기며 목가적인 호수 근처에 살고 있다. 60세가 된 그에겐 이루고 싶은 또 다른 꿈이 있을지도 모르지만, 침묵을 포용한 그의 야망은 누그러졌다.

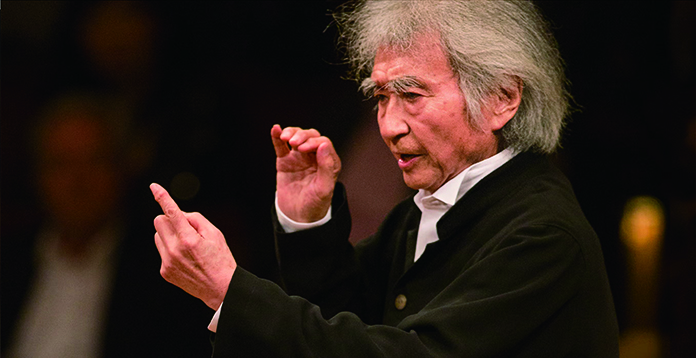

그에 대해 읽으면 읽을수록 나는 지휘자의 첫 번째 임무란, 신이 ‘그곳에 소리가 있게 하라’고 말하기 전에 존재한 소음이 없는 세상을 상상하는 것이라고 더욱더 확신하게 된다. 프란츠 벨저 뫼스트는 지휘대에서 음을 떼기 전, 일종의 명상 연습을 하는 것처럼 보인다. 역대 거장 카를로스 클라이버는 지휘를 시작함과 동시에 1분여간 숨을 내쉬지 않았고, 푸르트뱅글러는 지휘를 아예 하지 않은 것으로 유명하다. 위대한 지휘에 있어 침묵은 아마도 진정한 비밀일 것이다. 번역 김진

The Secret of Silence

노먼 레브레히트 칼럼의 영어 원문을 함께 제공합니다

The ugliest epithet ever attached to a conductor in my time was coined in the late 1980s when two London orchestras were fighting it out for the right to sole residency at the Royal Festival Hall. Neither organization was in good shape. The Philharmonia Orchestra was conducted by Giuseppe Sinopoli, an Italian psychoanalyst whose ideas floated above the players’ heads. The London Philharmonic was losing the inspirational Klaus Tennstedt to cancer and players were unsure about his successor, a bespectacled Austrian, not yet 30, who went by the assumed name of Franz Welser-Möst.

Two backbench musicians duly dubbed him Frankly Worse than Most, an insult aimed not just at the man but the entire maestro breed. All conductors, the tag implied, were rubbish. This one was just WTM.

When the nickname appeared in a concert review, its subject offered his resignation. The players begged him to stay, fearing his exit might cost them the residency. Seven years later, when he left London for good, one barbed critic wrote ‘he came from nowhere, he’s going nowhere.’ Sinopoli, also run out of town, died aged 55, in the middle of conducting Aida in Berlin. The two orchestras agreed to split the residency and have resented it ever since. All that endures of the episode is a sour aftertaste of how unpleasant classical music can be.

Franz Welser-Möst, now 60, revisits his ordeal in a new memoir entitled From Silence: Finding Calm in a Dissonant World. He describes how it felt to be ‘used as a buffer by several interested parties; the low blows became more and more powerful while support from the orchestra became ever weaker.’ What did he learn? Shut out the ambient noise, he advises, and ‘discover that we can trust in silence’.

The remedy has served him well. Since the turn of the century, Welser-Möst has been music director of the Cleveland Orchestra, the most accomplished in America. In the world’s most competitive market, he has maintained a translucent sound and refined it to a richness unmatched in R. Strauss and a delicacy rare in Bartok. Two decades in Cleveland have vindicated his abilities. The point of his memoir is to look beyond the conflicts of his life to a stillness he discovered a moment before he almost died.

On November 19, 1978, the 150th anniversary of Franz Schubert’s death, he was in a car on the way to a concert when the driver lost control on an Alpine road. The woman in the seat beside him was killed. Franz, 18, woke up in hospital with broken fingers and a damaged spine, ending his hopes of being a violinist. In the instant before the accident – he is convinced it was before – ‘an unbelievable silence’ embraced him.

‘I was completely at its mercy,’ he writes, ‘unable to move, let alone to influence what would happen in the seconds ahead. This silence seemed to me to ignore all the known rules of the world… Since that day I have thought repeatedly about the phenomenon of silence… silence as a condition of the absence of sound.’

The idea of silence as music was articulated by the American composer John Cage who associated silence with chance or aleatory events in which the unforeseen must always be expected. The random variable in Franz’s life was a Liechtenstein baron called Andreas von Bennigsen who, dandled as a boy on Wilhelm Furtwängler’s knee, spent his time searching for a comparable genius. Declaring he had found his grail in the town of Wels, he double-barrelled Franz Möst’s surname and adopted him as his son and heir. His parents, a doctor and an MP, seem to have raised no objections.

If that sounds weird, the baron proved positively wacko. By the time Franz detached himself, the surname had stuck and his star was rising on EMI Records. The first time I saw him conduct, deputising for Tennstedt on tour at a suburban Tokyo hall, he spent the concert interval throwing up and came out to give the most electrifying Beethoven’s 5th symphony I have ever heard in the flesh. From that night on, I have never doubted his capacity for self-inspiration.

In the aftermath of his London debacle, he spent a convalescent 15 years at Zurich Opera, working with an orchestra of watchmakers and an ensemble of many talents, among them the young Jonas Kaufmann. One summer’s night I heard him take the prelude to Der Rosenkavalier at twice the normal speed. Why? I asked. ‘Because we can,’ grinned Franz. ‘It has been a long season and we needed to let loose.’

In Cleveland, he faced hostility from the city’s only music critic and testified in his dismissal lawsuit. Retiring senior players raised ripples of dissent but his tenure has been on the whole benign and the musical quality – in a rustbelt city of staggering deprivation, sublime. Apart from a brief spell as music director of the Vienna Opera, his progress since London has been unruffled. The memoir is dedicated ‘to my dear wife, Geli’. He lives beside an idyllic lake, cherishing ‘the possibility of retreat into the silence of contemplation.’ At 60 he may have one more career Alp to climb, but the ambition gene is tempered by his embrace of silence.

The more I read him, the more convinced I am that the first duty of a conductor is to imagine a world without noise, the primal chaos that existed before God said, let there be sound. On the podium, Franz Welser-Möst appears to practice some form of meditation before he gives a beat. Carlos Kleiber, the all-time maestros’ maestro, used to flutter around for a minute or more before exhaling. Furtwängler was famed for giving no beat at all. Silence may well be the true secret of great conducting.

글 노먼 레브레히트 영국의 음악·문화 평론가이자 소설가. ‘텔레그래프’지, ‘스탠더즈’지 등 여러 매체에 기고해왔으며, 지금 이 순간에도 자신의 블로그(www.slippedisc.com)를 통해 음악계 뉴스를 발 빠르게 전한다