노먼레브레히트 칼럼 | | SINCE 2012

영국의 평론가가 보내온 세계 음악계 동향

나는 왜 베토벤의 ‘전원’ 교향곡을 증오하는가

작품 속 숨겨 놓은 작곡가 내면의 의미

호러스 베르네 ‘나폴레옹 프리틀란트 전투’

나는 걸음마를 떼기 전부터 음악을 사랑했다. 자매들이 노래하면 그게 무슨 곡이든 화음을 맞췄으며, 행운이자 저주이기도 한 절대음감으로 잘못된 음에 울부짖기도 했다. 그러다가 베토벤의 교향곡 6번 ‘전원’을 처음 들었던 순간, 음악을 증오하게 됐다.

두 살 때 어머니가 돌아가신 뒤로, 아버지는 내가 아홉 살 때 히틀러 정권의 난민이자 망명으로 정신이 불안정했던 새어머니와 재혼하셨다. 새어머니는 로열페스티벌홀 오케스트라 공연에 나를 데려갔다. 그는 사람들로 북적이는 모든 유명 공연을 좋아했고, 그중 가장 좋아하는 것은 집에서도 이동식 축음기로 틀어 두던 ‘전원’ 교향곡이었다. 그리하여 나는 ‘전원에 도착하자 마음에서 일어나는 가득한 생기’로 북적이는 현악기 도입을 비난하는 어른으로 성장했다. 마치 곧 끔찍한 시간이 다가온다고 예고하는 듯했기 때문이다.

새어머니가 지하철 메트로폴리탄선의 종점, 인적이 드문 곳에 나를 데려가 하루 종일 이어지는 산책을 하는 것도 내가 증오하던 또 다른 방식의 삶의 침범이었다. 영국의 시인 존 베처먼(1906~1984)은 루즐립과 아머샴 지역 근처의 ‘잃어버린 엘리시움’이라며 이를 격찬할지도 모르겠으나, 내게 이 역들은 등 뒤로 맨 배낭과 더불어 불행에 젖은 불길한 전조였다. 나는 신에게 날 붙잡은 이를 향해 벼락이라도 내려 죽음으로 인도하기를 빌거나, 농부가 무단침입이란 죄로 새어머니를 향해 방아쇠를 당겨주길 기도했다. 내 발목이 부러지길 바라며 등산화 끈을 묶지 않은 채 두기도 했고, 학교에서는 지리학에 낙제해 램블러 협회에서 만드는 비닐 지도도 읽을 줄 모른다는 의심까지 받아 봤다.

음악을 즐기기 위한 노력

전원적인 그 모든 것에 대한 혐오는 10대 후반까지 지속됐으나, 타국 땅에서 다른 언어를 사용하는 끈기 넘치는 여자친구가 나를 오케스트라 공연과 불모지 산책으로 이끌었다. 교향곡 공연을 전전하니 그제야 나는 음악을 감각적 환희로, 그 어떤 예술로도 가닿을 수 없던 나의 영혼을 향해 가는 입구로 받아들였다. 브람스·엘가·드보르자크·말러 사이를 오가며 사랑과 죽음, 과거와 현재, 순간과 영원을 단숨에 불러일으키는 음악의 표현 능력을 칭송하게 됐다. 음악은 12개짜리 음으로 그 모든 것을 말할 수 있다. 프로이트를 능가하는 쇤베르크의 분석적인 추론을, 자신에게 내제된 소련의 존재에 반항하는 쇼스타코비치의 불타오르는 역설을 들었다.

물론 여전히 경계하지만, 나는 ‘전원’ 교향곡을 슈만의 목가적인 교향곡 3번, 브람스의 교향곡 2번, 세자르 프랑크의 교향곡, 브루크너, 시벨리우스, 랠프 본 윌리엄스로 이어지는 행렬의 일부로, 무엇보다 숨이 막힐 듯 파멸에 잠식된 유년기를 떠올리게 하는 교향곡 1번이 포함된 구스타프 말러의 세계로 향하는 진입점으로 받아들였다. 그 후 말러는 내게 공생 관계로 고착됐다. 하지만 상트페테르부르크에서부터 시러큐스까지 그의 행적을 따르며 자필 서명 악보를 탐독하고 여러 음반을 들은 뒤 내가 만난 것은 감정적 장벽이었다.

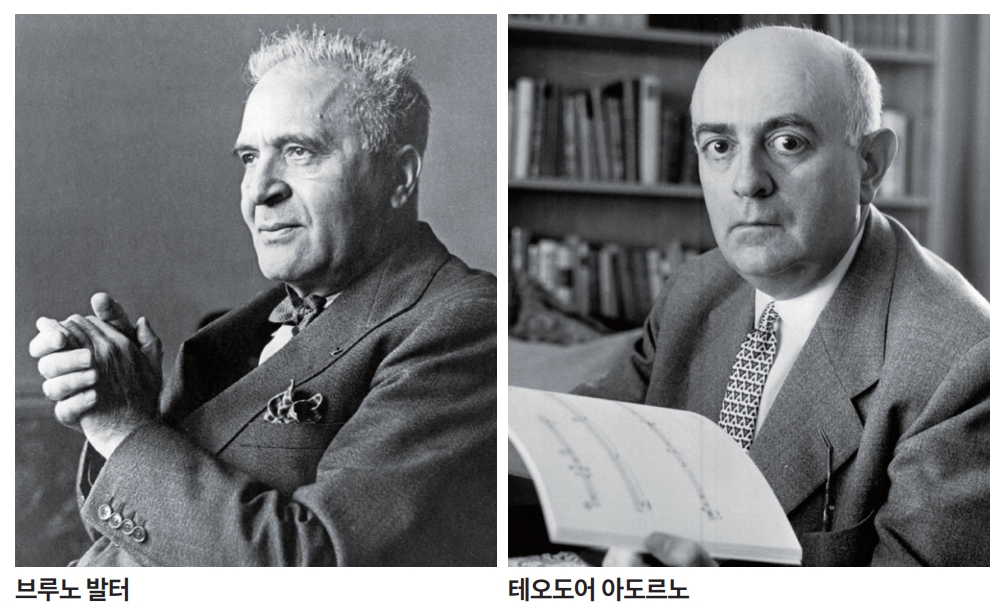

말러가 신뢰한 해석자였던 지휘자 브루노 발터(1876~1962)는 새어머니가 뮌헨에서 성장할 당시 독일에서 엄청난 권위를 지닌 지휘자이자 바이에른 슈타츠오퍼의 음악감독이었다. 날 붙잡은 이가 필립스사 턴테이블이 고장 날 때까지 틀어댔던 것 또한 발터가 지휘한 ‘전원’ 교향곡 LP였다. 새어머니의 눈에는 발터가 신실해 보였겠지만, 내게는 말러의 세계로 더 깊숙이 파고들기 전에 퇴마해야 할 악마였다.

내 사진첩에는 땅딸막한 발터가 부티 나는 차림으로 이웃인 소설가 토마스 만(1875~1955)과 정원에서 점심 식사를 하는 사진, 지휘자 아르투로 토스카니니(1867~1957)와 잔을 맞대는 사진, 뮌헨의 대교주이자 차기 교황의 손등에 입을 맞추는 사진이 있다. 그는 전형적인 고위층 부르주아의 철옹성 같은 매력 그 자체였다.

두 얼굴의 사람들, 두 얼굴의 음악

그러나 나는 이내 그의 감춰진 약점을 알게 됐다. 기록과 구두로 전해진 내용에 따르자면 브루노 발터는 정부를 두었으며 이웃의 십대 소녀를 유린한, 엄밀히 말하자면 성폭행한 성범죄자였다. 나치로 인해 강제로 추방당한 발터는 토마스 만의 집 근처인 미국 퍼시픽 팰리세이즈에서 꿈에 그리던 생활을 시작했다. 전쟁이 끝나자 재빠르게 과거 나치 측에 섰던 빈 필의 오명을 가렸으며, 1947년 8월 제1회 에든버러 페스티벌에서 빈 필의 지휘를 맡았다. 그 공연은 영국 관객에게 베토벤의 ‘전원’ 교향곡과 말러의 ‘대지의 노래’ 연주의 정석이 됐다. 1962년 숨을 거둘 때까지 발터는 지휘자 게오르그 솔티, 주빈 메타를 발탁하며 자문 역을 공고히 했다.

인간 브루노 발터를 파헤친 것은 내게 음악적 자유를 주었다. 이제 나는 할리우드 오케스트라와 녹음한 그의 ‘전원’ 교향곡을 들을 수 있다. 심지어 그가 영화계 거물과 흥행작을 좇는 관객들이 가진 연속된 망상을 잘 이어 붙여 이용했음을 들을 수도 있다. 이는 재능의 축복을 받은 거장만이 불러낼 수 있는, 온기와 색채가 우아하게 표현된 모범적인 음반이다. 또한 음악이, 특히 ‘전원’ 교향곡이 그 자체와 무관한 요구에 어떻게 적응할 수 있는지를 보여주는 좋은 예시이기도 하다.

전 보그 편집자이자 흐려져 가는 미모의 한 미국인 여성이 한때 파리에서 헤르베르트 폰 카라얀(1908~1989)에게 “오직 한 사람, 당신을 위해서 ‘전원’ 교향곡을 연주하겠다”라고 들은 적이 있음을 내게 알려주었다. 그와 비슷한 여러 호색한 일화를 들은 적도 있는데, 언제나 ‘전원’ 교향곡과 관련이 있다. 이 규정되지 않은 교향곡에는 ‘즉석 만남’의 구실로 작용하는 무언가가 분명 존재하는 모양이다.

베토벤이 만들어낸 여러 결과의 완전성을 고려해보았을 때, 전원 교향곡은 그의 곡 중에서 가장 생뚱맞은 존재이다. 이 곡이 쓰이지 않았더라면 베토벤에 대한 우리의 관점도 변하지 않았을 것이다. 전원 교향곡은 교향곡 5번과 피아노 협주곡 4번 사이에 작곡됐고, 1808년 12월의 기나긴 공연에서 초연됐다. 앞뒤로 작곡된 두 작품은 나폴레옹이 빈으로 향하는 길목을 맹공했던 불안한 정세를 담고 있다.

하지만 교향곡 6번은 순수한 현실 도피이자 깊은 겨울의 한복판에 도래한 봄 나절로 베토벤이 전혀 한 적 없던 이야기를 풀어낸다. 아침에 일어나 초원으로 산책을 나간다. 개울가에 앉는다. ‘시골 사람들의 단란함’(3악장)을 구경하고 고개를 들어 폭풍우를 본다. 피난처를 찾는다. 폭풍이 불어 닥친다. ‘기쁘고 감사한 감정’에 빠진다. 진부하다고? 맞는 말이다. 따분하다고? 굉장히 맞는 말이다. 베토벤 작품이라는 생각이 들지 않는다.

조금만 더 조사해본다면 석연치 않은 구석을 찾을 수 있다. 베토벤은 전원 교향곡의 악장 제목을 문자 그대로 받아들여서는 안 된다는 메모를 남겼다. 그가 모호한 구석을 만들어 둔 이 교향곡은 이야기를 음악으로 묘사하는 ‘음화(tone-painting)’보다 더 풍부한 표현력을 지닌다. 영국 국립 도서관 온라인 페이지에서도 확인할 수 있는 악보 스케치에서 그는 이렇게 말하고 있다. “해석은 청자의 몫이다.” 오, 루트비히. 정말 감사한 일이 아닐 수 없다.

전원 뒤에 숨겨진 그림자

여전히 우리에게 시냇물은 졸졸 흐르고 새는 지저귀며 천둥은 무섭게 들린다. 베토벤은 두 가지 모두를 시도하려 애썼다. 그는 적어도 불안정한 당대 정치사회 상황과는 전혀 동떨어진 이 목가적인 전원생활이 불편했고, 일정 부분 거짓이라는 걸 알았다. 베토벤은 변칙을 토로하고 있는데, 그럼 청자인 우리의 해석은 무엇인가?

브루노 발터와 토마스 만의 퍼시픽 팰리세이즈 이웃, 철학자 테오도어 비젠그룬트 아도르노(1903~1969)는 흥미로운 해석을 들이민다. 자신의 미완성 에세이에서 아도르노는 다음과 같이 주장한다. “베토벤의 음악은 위대한 철학이 세상을 이해하는 과정에 대한 인상이다. 그러므로 여기서 인상이란 세상 그 자체가 아닌, 세상에 대한 해석이다.” 그는 베토벤이 ‘전원’ 교향곡에서 그린 모든 것이 현실과는 동떨어져 있으며, 그 음악 자체가 그것을 위한 주석이자 해석이라 말한다.

이를 뒷받침하기 위해 아도르노는 ‘전원’ 교향곡의 피날레를 예로 든다. 모두가 행복한 결말로 달려갈 때 베토벤은 순박한 목동의 노래로 절정의 긴장이자 ‘비밀스러운 부정성’을 만들어 냈다고 설명한다. 유튜브에서 레너드 번스타인의 빈 필 녹음 후반부를 들어보라. 그 무엇도 진실처럼 들리지 않을 것이다.

이는 내게 커다란 울림을 주었다. 베토벤이 ‘텍스트’와 ‘서브텍스트’, 서술적 묘사와 분석을 둘 다 전달한다는 아도르노의 주장을 받아들인다면 ‘전원’ 교향곡을 일요일의 즐거운 소풍, 자멸로 향하는 세계에 대한 우레와 같은 설교 등 우리의 취향대로 탈바꿈할 수 있다. 선율을 사랑할 수도, 개인적인 암시를 혐오할 수도 있다. 좋든 싫든 간에, ‘전원’ 교향곡을 향한 나의 상반된 감정에 대한 치유책을 ‘전원’ 교향곡 속에서 찾을 수 있었다.

베토벤은 작품을 마치며 부정적인 생각에 사로잡혀 괴로워했다. 여행기, 전원생활의 풍자, 낙원과도 같은 시골을 ‘성급한 왜곡’으로 창조한 것은 아닌지 자문하는 그를 그려본다. 베토벤은 이렇게 말한 적도 있다. “자신의 오류를 스스로 인정하는 것보다 더욱 견디기 어려운 것은 없다.” ‘전원’ 교향곡에서 그는 우리를 은밀한 곳으로 안내한다. 베토벤은 시골의 일상을 사랑했고, 그 일상에서 나온 작품으로부터 뒷걸음쳤으며, 결국 우리에게 사랑과 증오 사이의 선택지를 남겨주었다. 그의 말에 따르자면, “해석은 청자의 몫이다.” (노먼 레브레히트는 ‘왜 베토벤인가’를 2월에 출간(Oneworld Publications) 한다)

번역 evener

번스타인/빈 필

베토벤 교향곡 6번 ‘전원’

노먼 레브레히트 칼럼의 영어 원문을 함께 제공합니다.

본 원고는 본지의 편집 방향과 일치하지 않을 수 있습니다.

I loved music before I could walk. It seemed I could harmonize anything my sisters were singing. I had perfect pitch, a mixed blessing since wrong notes made me cry.

I hated music when I first heard Beethoven’s Pastoral Symphony.

I was nine years old. My mother had died when I was two and my father got remarried to a Hitler refugee, half unhinged by exile. My stepmother took me to orchestral concerts at the Royal Festival Hall. She liked all the crowd pleasers, best of all the Pastoral Symphony which she played at home on a portable gramophone. I grew to revile the opening rustle of strings, ‘the awakening of cheerful feelings on arrival in the countryside.’ It told me I was in for a rotten time.

My hated stepmother’s other incursion was to take me on daylong rambles at the semi-inhabited end of the Metropolitan Line. John Betjeman may have extolled a ‘lost Elysium’ around Ruislip and Amersham. For me, these stations portended sodden misery with a rucksack on my back. I prayed to God for lightning that would strike my captor dead or a farmer who would shoot her for trespass. I left my Millets bootlaces untied in the hope of breaking an ankle. I failed Geography at school so that I could not be trusted to decipher a plastic-wrapped Ramblers Association map.

My aversion to all things pastoral endured into my late teens when, in another country and a different language, a patient girlfriend took me to orchestral concerts and desert walks. Symphony after symphony, I embraced music both as sensory pleasure and as a portal to parts of my psyche no other art could reach. I cycled through Brahms, Elgar, Dvorak and Mahler, exalted by the capacity of a musical phrase to evoke, at once, love and death, then and now, here and forever. Music could say it all in a dozen notes. I heard an analytic reasoning in Schoenberg that surpassed Freud and a crackling irony in Shostakovich that defied his Soviet existence.

Still wary of hearing the Pastoral, I accepted it as the matrix of Schumann’s bucolic third, Brahms’s second, the César Franck D minor, Bruckner, Sibelius, Vaughan Williams – above all, as an entry point to the world of Gustav Mahler whose first symphony evokes an oppressive, doom-laden childhood. Mahler became, for me, a symbiotic fixation. I followed his trail from St Petersburg to Syracuse, pored over autograph scores, listened to recordings – and then hit an emotional barrier.

Mahler’s trusted interpreter was Bruno Walter, a conductor of magnificent authority who while my stepmother grew up in Munich, was Generalmusikdirector – God, in a compound German noun. It was Walter’s Pastoral LP that my tormentor wore out on her Philips turntable. Walter, in her eyes, was divine. I would have to exorcise this demon before I could go any deeper into Mahler.

My picture files showed the chubby Walter expensively tailored, at a garden lunch with his neighbour Thomas Mann, clinking glasses with Arturo Toscanini, kissing hands with the archbishop of Munich, the next Pope. He personified the impervious charm of the higher bourgeoisie.

But I soon found feet of clay. Archives and oral memories showed up Bruno Walter as a sex pest who kept a mistress on tap and seduced, technically raped, his neighbour’s pubescent daughter. Forced into exile by the Nazis, Walter resumed his lotus life in a house near Mann’s on Pacific Palisades. The War over, he quickly whitewashed the Vienna Philharmonic of Nazi crimes and conducted them at the inaugural Edinburgh Festival in August 1947 in concerts that were, for British audiences, formative readings of Beethoven’s Pastoral and Mahler’s Song of the Earth. Up to his death in 1962, Walter was consulted as an oracle by rising conductors Georg Solti and Zubin Mehta.

Unpicking the human Walter was musically liberating for me. I could now listen to his Pastoral recording with a Hollywood orchestra and hear him adjusting – pandering, even – to the panoramic delusions of movie moguls and drive-in audiences. It is an exemplary recording, elegantly phrased and executed with a range of warmth and colours that only the most gifted of maestros can summon. It is also an object lesson in how music – particularly the Pastoral Symphony – can be adjusted to unrelated demands.

I remember hearing from a former Vogue editor, an American lady of faded beauty, that Herbert von Karajan told her once in Paris that he was about to perform the Pastoral ‘for one person only, just for you.’ I heard similar concupiscent anecdotes, always to do with the Pastoral. Clearly, there must be something else going on in this ambiguous symphony for it to work as a speed-dating line.

Considered in the totality of Beethoven’s output, the Pastoral is a cuckoo in his list. Had it never been written, our view of him would not change. It was composed alongside the fifth symphony and fourth piano concerto and premiered together in an overlong concert in December 1808. Both of the other works reflect nervous times, Napoleon hammering at the gates of Vienna.

The sixth, however, is sheer escapism, a springtime day evoked in deep midwinter and telling a story, which Beethoven never does. Chap gets up in the morning, goes for a walk in a meadow. Sits down beside a brook. Watches a ‘merry gathering of country folk’ (Beethoven’s third movement title), looks up and sees a storm cloud. Finds shelter. Storm blows over. Chap admits to ‘cheerful and thankful feelings’. Cliché? You said it. Banal? Absolutely. Surely not by Beethoven.

Research a little further and you’ll find signs of his ambiguousness. Beethoven left a note saying that his movement titles in the Pastoral are not to be taken literally. The symphony, he hedges, is ‘more expression than tone-painting.’ He goes on to say (in a sketch now online at the British Library), ‘one leaves it to the listener to work out the situations.’ Well, thanks for that, Ludwig.

Still, we hear the brook babbling away like a brook, the bird trills and the thunder is meant to terrify. Beethoven is trying to have it both ways. He is not comfortable with this idyll of country life that he knows to be, at least in part, untrue and entirely out of context for the brittle social and political situation of his times. He confesses to the anomaly. So what are we, as listeners, to make of it?

The philosopher Theodor Wiesengrund Adorno, a Pacific Palisades pal of Walter and Mann, comes up with an intriguing exegesis. In an unfinished essay Adorno argues that ‘Beethoven’s music is an image of that process which great philosophy understands the world to be. An image, therefore, not of the world but of an interpretation of the world.’ What he is saying is that everything Beethoven does in the Pastoral is at one remove from reality, a text that is also a commentary on itself.

By way of proof, Adorno demonstrates that in the finale of the Pastoral, when all is heading for a happy ending, Beethoven out of the supposed naivety of a shepherd’s song generates climactic tension, a ‘secret negativity’. Just listen to the closing pages in, for instance, Leonard Bernstein’s Vienna Philharmonic recording on Youtube. Nothing rings quite true.

This, for me, cuts to the chase. If we accept Adorno’s proposition that Beethoven delivers both text and subtext, narrative and analysis, we can make of the symphony whatever we like – either a jolly Sunday jaunt or a thunderous sermon against a world bent on self-destruction. We can both love the melodies and loath the personal connotations. Love it or hate it, within the Pastoral I can find a therapeutic resolution of my conflicted feelings towards it.

Beethoven, finishing the work, is beset by negativity. I picture him wondering if he hasn’t turned out a piece of travel journalism, a parody of country life, a rushed distortion of rural paradise. ‘Nothing,’ he once said, ‘is more intolerable than having to admit to yourself your own errors.’ In the Pastoral he lets us into that furtive admission. He adores country life and recoils from what he has made of it. In the end he leaves us to choose between love and hate. In his words: ‘one leaves it to the listener to work it out.’

Why Beethoven, by Norman Lebrecht, is published by Oneworld on February 2, price £20.

글 노먼 레브레히트

영국의 음악·문화 평론가이자 소설가. ‘텔레그래프’지, ‘스탠더즈’지 등 여러 매체에 기고해왔으며, 지금 이 순간에도 자신의 블로그(www.slippedisc.com)를 통해 음악계 뉴스를 발 빠르게 전한다