노먼레브레히트 칼럼 | SINCE 2012

영국의 평론가가 보내온 세계 음악계 동향

초가을을

위한 뜻깊은

음반들

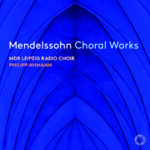

마지막 역작부터 첫 소개의 설렘까지

상당히 침체한 올여름의 공연계에서 나의 이목을 놀라게 했던 몇 레이블의 비범하고도 매력적인 음반을 소개한다.

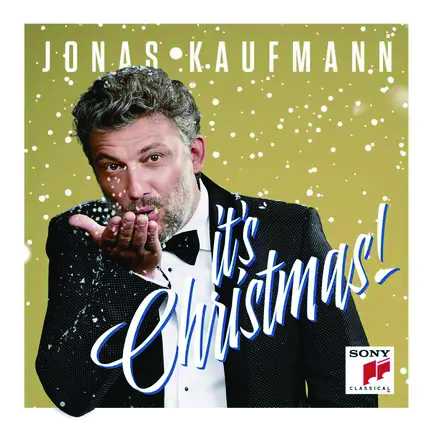

무한의 항해

Alpha ALPHA1000

바버라 해니건(소프라노)/ 베르트랑 샤메유(피아노)/ 에머슨 콰르텟

손수건을 준비할 시간이다. 47년간 현악 4중주단의 최전방에 있었던 에머슨 콰르텟이 이번 여름에 은퇴할 예정이며, 본인들의 남은 생을 새로운 콰르텟 육성에 바치기로 했다. 두 명의 바이올리니스트 유진 드러커(1952~)와 필립 세처(1951~)는 창단 멤버로, 미국 건국 200주년인 1967년부터 함께했다. 비올리스트 로런스 더튼(1954~)은 1977년부터 자리를 지켰고, 첼리스트만 변화가 있었다. 수년간 에머슨 콰르텟이 보여준 놀라운 일관성과 성공적인 연주는 부에나 비스타 소셜 클럽부터 롤링 스톤스까지, 오직 소수의 단체만 가질 수 있는 전유물이었다.

손수건을 준비할 시간이다. 47년간 현악 4중주단의 최전방에 있었던 에머슨 콰르텟이 이번 여름에 은퇴할 예정이며, 본인들의 남은 생을 새로운 콰르텟 육성에 바치기로 했다. 두 명의 바이올리니스트 유진 드러커(1952~)와 필립 세처(1951~)는 창단 멤버로, 미국 건국 200주년인 1967년부터 함께했다. 비올리스트 로런스 더튼(1954~)은 1977년부터 자리를 지켰고, 첼리스트만 변화가 있었다. 수년간 에머슨 콰르텟이 보여준 놀라운 일관성과 성공적인 연주는 부에나 비스타 소셜 클럽부터 롤링 스톤스까지, 오직 소수의 단체만 가질 수 있는 전유물이었다.

창단 역시 대단히 뜻깊다. 이들은 미국의 줄리아드 음악원에서 결성하여 미국 시인 랠프 월도 에머슨(1803~1882)의 이름을 따왔는데, 이미 상당한 정확성과 더불어 불가능을 손쉽게 가능으로 바꾸는 유망함을 지니고 시작했다. 에머슨 콰르텟은 유행, 정치, 평등에 대한 압박에서 벗어나 광활하고도 영원한 전통의 물결 속에 정착했고, 이들이 남긴 음반은 바흐에서 브리튼, 하이든에서 존 하비슨(1938~)에 이른다. 구심점을 새롭게 정의한 이들과 같은 존재를 우리는 이후 음반사에서 찾을 수는 없을 것이다.

이 마지막 음반(‘Infinite Voyage’)은 참여 연주자들로 인해 편성을 확장한 점에서만 에머슨의 전형을 비껴가고 있다. 모험심 가득한 소프라노 바버라 해니건(1971~)이 합류하여 파울 힌데미트의 잘 알려지지 않은 작품 ‘멜랑콜리(Mélancolie)’, 에르네스트 쇼송의 달콤한 ‘영원한 노래(Chanson perpétuelle)’를 함께 한다. 전자는 무조성의 절벽 위에서 버티고 서있는가 하면, 후자는 너그러운 타락을 선보인다. 두 작품 모두 앞으로 즐겨 듣게 될 것 같다. 음반의 중심은 알반 베르크의 현악 4중주 Op.3으로, 아르놀트 쇤베르크의 제자였던 그가 조성이라는 쾌락 욕구를 거부하기 위해 최선을 다했으나 실패한 작품이다. 덕분에 베르크의 작품들은 하나같이 사랑스럽기 그지없다.

해니건은 쇤베르크의 문제작인 현악 4중주 2번에서 다시 등장한다. 여기서 작곡가는 소프라노에게 어떤 조성도 없는 상태로 악보 몇 페이지를 거닐게 한다. 모든 20세기 음악학자는 이 작품을 훤히 꿰고 있지만, 상당수의 감상자는 여전히 작곡가의 동기에 의문을 품고 있다. 개인적으로 이 녹음이 지금껏 들었던 어떤 연주보다 명확하게 이 작품을 해석했다고 본다. 이 작품은 알려지지 않은 무조성의 세계를 소개하는 쇤베르크의 신념이 모범적으로 담겼는데, 오직 열린 마음과 칼날 같은 테크닉, 무한한 유연성을 지닌 음악가만이 이를 구현할 수 있다는 걸 에머슨 콰르텟이 보여준다. 우리는 이 현악 4중주단을 몹시 그리워할 게 분명하다.

바체비치 : 피아노 협주곡 외

Ondine ODE1427-2

페테르 야블론스키·엘리자베트 브라우스(피아노)/니컬러스 콜론(지휘)/핀란드 방송교향악단

20세기를 통틀어 그라지나 바체비치(1909~1969)만큼 규정하기 어려운 작곡가가 또 있을까? 바체비치는 보통 폴란드 작곡가로 명명되나 그의 아버지는 1918년 리투아니아가 독립하자 가문을 떠난 리투아니아인이었다. 바체비치의 오빠 비타우타스 바체비추스(1905~1970)는 뉴욕에서 작곡가로 활동했으며, 바체비치 본인은 폴란드 국립 방송교향악단의 악장으로서 높은 연봉을 받으며 폴란드 바르샤바와 우치를 오갔다. 상황에 따라, 또한 결혼과 자녀로 인해 폴란드인이 되었으나, 그의 소리는 시마노프스키, 루토스와프스키, 안제이 파누프니크, 펜데레츠키로 이어지는 폴란드 작곡가의 계보에는 왠지 맞지 않는다. 바체비치는 주변인이었으나 이는 여성이라는 이유 때문이 아니었다. 그가 스스로 거리를 둔 것이다.

20세기를 통틀어 그라지나 바체비치(1909~1969)만큼 규정하기 어려운 작곡가가 또 있을까? 바체비치는 보통 폴란드 작곡가로 명명되나 그의 아버지는 1918년 리투아니아가 독립하자 가문을 떠난 리투아니아인이었다. 바체비치의 오빠 비타우타스 바체비추스(1905~1970)는 뉴욕에서 작곡가로 활동했으며, 바체비치 본인은 폴란드 국립 방송교향악단의 악장으로서 높은 연봉을 받으며 폴란드 바르샤바와 우치를 오갔다. 상황에 따라, 또한 결혼과 자녀로 인해 폴란드인이 되었으나, 그의 소리는 시마노프스키, 루토스와프스키, 안제이 파누프니크, 펜데레츠키로 이어지는 폴란드 작곡가의 계보에는 왠지 맞지 않는다. 바체비치는 주변인이었으나 이는 여성이라는 이유 때문이 아니었다. 그가 스스로 거리를 둔 것이다.

나치의 폴란드 점령으로 공연 가능성이 전혀 없던 시기에도 바체비치는 작곡을 이어 나갔다. 1943년 작곡된 터무니없이 명랑한 서곡은 1945년 9월에 초연되었다. 도대체 그 마음속에는 무엇이 존재했던 걸까? 희망일까, 조롱일까? 눈을 가린 채 이 작품을 들으면 아서 블리스(1891~ 1975)나 프랑스 6인조의 현란함이 가득한 곡으로 오해할 수도 있다. 진정한 바체비치가 잘 떠오르지 않는다.

스탈린의 사회주의 리얼리즘 하에 작곡한 1949년의 첫 번째 피아노 협주곡은 버르토크와 스트라빈스키 사이 그 어디에도 뿌리내리지 못한 채 부유한다. 바체비치는 자신의 의도를 고의로 모호하게 유지했다. 조금 더 나아진 환경에서 작곡한 1966년의 두 대의 피아노를 위한 협주곡은 당대 모더니즘과의 유사성을 드러냈다가 결국엔 배신하는 작품으로, 작곡가가 클러스터와 음렬주의로 향한다고 생각한 순간 다시 조성음악적 형식과 화성으로 돌아간다.

바체비치에게는 광대한 에너지가 있으나, 나는 이를 정확하게 포착하고 해석한 음반을 만나지 못했다. 피아니스트 페테르 야블론스키(1971~)는 이번 음반에서 빛을 발하며, 니컬러스 콜론(1983~)은 핀란드 방송교향악단을 극적인 역동성으로 지휘한다. 바체비치를 계속해서 좋아하고 싶지만, 폴란드에서 역사상 최악의 시기를 살아낸 작곡가가 후세에게 본인의 경험 전부를 내어 주지 않았다는 점을 이해하기 어렵다. 그게 어떻게 가능하겠는가?

멘델스존 코랄 작품

Pentatone PTC5187064

필리프 아만/라이프치히 방송 합창단

헨젤: 가곡

First Hand FHR148

제니퍼 파커·스테퍼니 웨이크 에드워즈(메조소프라노)/ 팀 파커 랭스턴(테너)/잼스 콜먼·제네비브 엘리스·이완 길퍼드(피아노)

남매 관계인 두 명의 작곡가를 비교할 기회는 자주 오지 않는다. 사실 멘델스존 남매를 제외한 사례로는 모차르트와 그의 불운한 누이 ‘난네를’(1751~1829, 마리아 안나 모차르트의 애칭)이 거의 전부라고 할 수 있다. 멘델스존 가에서 먼저 두각을 드러낸 것은 누나인 파니 멘델스존(1805~1847)이었으나, 어린 동생 펠릭스에게서 모차르트와 비슷한 영재의 모습이 보이자, 그들의 아버지는 파니를 침묵시켰다. 뜻이 꺾인 파니는 결혼을 하고 가문에 성심을 다하다가 30대에 다시 작곡을 시작하며 펠릭스를 놀라게 했다. 이 두 음반에 수록된 곡들은 음조와 목적이 상이하다. 필리프 아만(1974~)의 지휘 아래 라이프치히 방송 합창단이 부른 펠릭스의 찬송가는 신성한 숭배를 위한 공개적인 낭송이다. 격식 있고, 쉽게 따라 부를 수 있는 이 곡들은 독실한 인간이 창조주를 외칠 때 느끼는 자기 검열에 시달린다. 펠릭스는 신앙심이 깊은 부르주아들에게 감동을 주기 위해 애썼으며 어느 정도는 성공했다. 그러나 이 모음집 그 어디에서도 펠릭스의 강렬한 불꽃이 느껴지지는 않는다.

남매 관계인 두 명의 작곡가를 비교할 기회는 자주 오지 않는다. 사실 멘델스존 남매를 제외한 사례로는 모차르트와 그의 불운한 누이 ‘난네를’(1751~1829, 마리아 안나 모차르트의 애칭)이 거의 전부라고 할 수 있다. 멘델스존 가에서 먼저 두각을 드러낸 것은 누나인 파니 멘델스존(1805~1847)이었으나, 어린 동생 펠릭스에게서 모차르트와 비슷한 영재의 모습이 보이자, 그들의 아버지는 파니를 침묵시켰다. 뜻이 꺾인 파니는 결혼을 하고 가문에 성심을 다하다가 30대에 다시 작곡을 시작하며 펠릭스를 놀라게 했다. 이 두 음반에 수록된 곡들은 음조와 목적이 상이하다. 필리프 아만(1974~)의 지휘 아래 라이프치히 방송 합창단이 부른 펠릭스의 찬송가는 신성한 숭배를 위한 공개적인 낭송이다. 격식 있고, 쉽게 따라 부를 수 있는 이 곡들은 독실한 인간이 창조주를 외칠 때 느끼는 자기 검열에 시달린다. 펠릭스는 신앙심이 깊은 부르주아들에게 감동을 주기 위해 애썼으며 어느 정도는 성공했다. 그러나 이 모음집 그 어디에서도 펠릭스의 강렬한 불꽃이 느껴지지는 않는다.

파니는 작곡가 본인을 위해, 또는 응접실 접견을 위해 작곡했다. 대부분의 작품이 최근에서야 조명을 받았고, 그중 절반은 이 음반을 통해 처음 공개됐다. 의무나 감상에 얽매이지 않는 파니의 곡들은 고색창연한 섬세함을 지니고 있으며, 때로는 자기 성찰적이고 언제나 굳건하게 솔직하다. 무려 다섯 곡의 제목이기도 한 ‘갈망(Sehnsucht)’은 사랑 또는 억눌렸던 직업적 희망을 명백하게 표현하고 있다.

세 명의 영국인 성악가 팀 파커 랭스턴, 스테파니 웨이크 에드워즈, 제니퍼 파커가 올해 초 독일 라이프치히 멘델스존 하우스에서 피리어드 피아노(편집자 주_18~19세기 악기 제작 방식을 따라 구현한 시대 피아노) 음색으로 녹음했다. 노래는 경이롭고, 분위기는 몹시 훌륭하다. 내 유일한 불만은 음반 제목의 작곡가 이름이 ‘멘델스존’이나 ‘멘델스존-헨젤’이 아니라 그의 결혼 후 성인 ‘헨젤’로 적힌 것이다. 동생보다 훨씬 강렬한 성품을 지닌 파니는 자신의 작품이 발표되는 만족감을 막 즐기기 시작한 무렵인 42세의 나이에 뇌졸중으로 생을 마감한다. 슬픔을 가눌 길이 없었던 펠릭스는 해가 바뀌기도 전에 누이를 뒤따르고 만다. 두 사람의 특별한 관계에 대해서는 나의 저서 ‘천재와 불안(Genius and Anxiety)’에서 확인할 수 있다. 번역 evener

노먼 레브레히트 칼럼의 영어 원문을 함께 제공합니다 본 원고는 본지의 편집 방향과 일치하지 않을 수 있습니다

Infinite Voyage: Emerson Quartet (Alpha Classics) Prepare to shed a tear. After 47 years at the string quartet frontlines, the Emersons are breaking up this summer to spend the rest of their lives on their other passion – nurturing new quartets. Their two violinists – Eugene Drucker and Philip Setzer – have been there since the quartet’s formation in America’s bicentennial year; the violist Lawrence Dutton joined in 1977. Only the cello seat has seen changes. Few groups, from the Buena Vista Social Club to the Rolling Stones, have ever maintained such consistency at such high performance over so many years.

The foundation year is, to a degree, significant. This was an American group, forged at Juilliard to high precision and with a can-do outlook that made the impossible seem easy. Named for an American poet, the Emersons avoided pressures of fashion, politics and equity, settling on a swathe of tradition that was at once vast and eternal. Their recorded legacy runs from Bach to Britten, Haydn to Harbison. They redefined the centre ground. We will not see their like again on record.

This finale album is untypical of Emerson only in being augmented by an outsider. The adventurous soprano Barbara Hannigan joins them for an obscure Mélancolie by Paul Hindemith and an added-sugar Chanson by Ernst Chausson, one dangling over a cliff of atonality, the other indulgently decadent. Both are likely to form part of my regular listening.

The heart of the album is Alban Berg’s string quartet, opus 3, in which Arnold Schoenberg’s pupil does his best to deny the pleasure principle, and fails. Berg cannot compose other than lovely.

Hannigan returns for Schoenberg’s car-crash work, the second string quartet in which the composer frees the soprano soloist to roam several pages without a tonal key. Every 20th century music historian knows this work inside out, and many are still perplexed by the composer’s motivation. I don’t think I have ever heard the second quartet more positively presented, exemplifying Schoenberg’s conviction in a world of unexplored tones, requiring only musicians of open minds, laser technique and infinite flexibility to bring it to light. We are so going to miss this group.

Grażyna Bacewicz: Piano concertos (Ondine)

Is there a more elusive composer in the whole of the 20th century than Grażyna Bacewicz (1909-1969)? Bacewicz is usually designated a Polish composer but her Lithuanian father left the family after his state won independence in 1918. Her brother, Vytautas Bacevičius, was a composer in New York. Grazyna, landing a well-paid job as concertmaster of the national radio orchestra, shuttled between Warsaw and Łódź. She is Polish, then, by circumstance; also, by marriage and child. But her sound does not fit somehow in the Polish tapestry of Szymanowski, Lutosławski, Panufnik and Penderecki. She is an outsider, and not by reasons of gender. Bacewicz holds herself apart.

Under the horrors Nazi occupation, she carried on composing when there was no chance of getting performed. A ridiculously playful 1943 orchestra was premiered in September 1945. What on earth was in her mind – hope or mockery? Blindfold, you might mistake this piece for a frippery by Arthur Bliss or one of Les Six. The real Grazyna Bacewicz will not stand up.

A first piano concerto of 1949, written under Stalinist rules of ‘socialist realism’, flickers between fragments of Bartok and Stravinsky, taking root in neither. Bacewicz keeps her intentions wilfully obscure. A concerto for 2 pianos in the slightly easier climate of 1966 betrays some affinity with contemporary modernism, but just as you think she’s waving tone clusters and a serial row, she retreats right back into tonal form and harmonies.

There are immense energies in Bacewicz, but I’m not sure that any interpreter on record has yet nailed her character. Peter Jablonski is the dazzling pianist on this release. Nicholas Collon conducts with Finnish radio orchestra with too many dynamic extremes. I keep wanting to like Bacewicz more, but I find it hard to understand that a composer who lived in Poland through its worst era withholds the entirety of her experience from posterity. How is that possible?

Felix and Fanny Mendelssohn: Choral and vocal works (Pentatone/First Hand Records)

It’s not often one gets a chance to compare two composers who are brother and sister. In fact, apart from the Mendelssohns, there is hardly another instance except Mozart and his inauspicious sister, Nannerl. In the Mendelssohn family, Fanny was the first to show talent, only to be silenced by her father once young Felix displayed a boyish genius that many likened to Mozart’s. Fanny went off, got married, acted as family conscience and shocked Felix by taking up composing again in her thirties.

The works on these two albums are disparate in tone and intent. Felix’s psalms, sung by the Leipzig radio choir under Philipp Ahmann, are public declamations for divine worship. Formal and easily singable, they suffer from the self-restraint a devout person feels when addressing the Creator. Mendelssohn is out to impress the worshipful bourgeoisie and succeeds, more or less. Nowhere, however, in this compilation does one feel the spark of Felix on fire.

Fanny’s songs are written for herself and the drawing room. Most have only recently come to light. Half of the songs here are premiere recordings. Without needing impose or impress, Fanny’s songs have a delicate patina, at times introspective, always insistently communicative. Five are titled ‘Sehnsucht’, or ‘longing’, clearly an expression of repressed hopes, romantic or vocational.

Three English singers – Tim Parker-Langston, Stephanie Wake-Edwards and Jennifer Parker – recorded them early this year in the Mendelssohn House in Leipzig on what sounds like a period piano. The singing is admirable, the ambience exceptional. My only gripe is that the composer is titled on the cover by her married name ‘Fanny Hensel’, rather than a Mendelssohn, or Mendelssohn-Hensel. Fanny, a much stronger character than her brother, was just beginning to enjoy the satisfaction of seeing her first works in print when she died of a stroke, aged 42. Felix, inconsolable, followed her within a year (I write more of their unusual relationship in my book, Genius and Anxiety).

글 노먼 레브레히트