노먼레브레히트 칼럼 | SINCE 2012

영국의 평론가가 보내온 세계 음악계 동향

베토벤, 그는 대체 어떤 인물인가?

친우조차 알 수 없던 그의 진실한 내면을 찾아

오스트리아 빈 중심부의 베토벤 동상

평생 세계적인 명성을 펼치면서 동시에 전혀 알 수 없는 인물로 남을 수 있을까?

1827년 3월 26일 루트비히 판 베토벤이 눈을 감았을 때 ‘그’라는 사람에 대해 말할 수 있는 이는 없었다. 베토벤에게는 일생을 함께한 한 줌의 친구들과 그보다 많은 음악계 지인이 있었으나, 그들 중 말솜씨가 유창하거나 대화 주도권을 지닌 이도 베토벤에 대해 묘사할 말을 찾지 못했다. ‘오, 위대한 사람이었죠. 정말 안타깝습니다!’ 정도가 일반적인 대답이었다.

당대 유명 시인 프란츠 그릴파르처(1791~1872)가 베토벤을 기리는 묘비 추도문을 맡게 되었는데, 이는 상투적인 시적 표현에 잔뜩 기대어 작성됐다. 그래도 그는 1805년부터 베토벤을 알았던 덕에, 베토벤이 사람들을 피했던 이유에 관해 한 시구로 적어냈다. “그는 자신이 사랑하는 자연 안에서 세상에 저항할 무기를 찾지 못했다. 그래서 세상으로부터 도망쳤다. 그는 동료들에게 자신의 모든 것을 건넸지만, 아무런 보답을 받지 못한 채 물러났다.” 그릴파르처의 표현은 지나치기도 하고, 모두 맞는 사실이라고 할 수도 없지만, 세간의 대화가 자신을 방해할 수 없도록 베토벤 스스로 세상과 거리를두어, 세상이 그를 ‘알 수 없는 인물’로 만들었다는 부분은 분명 옳다.

그를 찾아 창작의 시작점으로

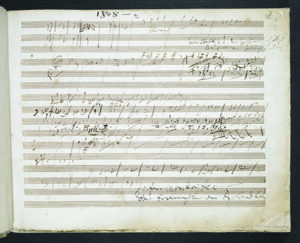

인물 기록 속 ‘알 수 없음’이라는 부분은, 책임감 있는 전기 작가라면 받아들여야만 하는 가정이다. 사건과 일화 속에서 인물을 끌어내려는 이들의 시도는 결국 실패로 끝난다. 베토벤은 자신을 추적하는 이들을 위해 덫을 놓았다. 그는 보이는 것과는 다른 사람이었으니 말이다. 나는 3년간의 연구를 엄격하게 그의 음악, 그중에서도 자필 악보만으로 진행하기로 결심했다. 요즘 시대에는 이를 손쉽게 온라인 디지털 자료로 열람할 수 있고, 그 위에 는 영감의 메모와 수정, 그의 다른 생각까지 충분한 단서가 존재한다. 예를들어, 베토벤은 왜 교향곡 6번 ‘전원’의 악장마다 부제를 적어놨을까? 그는 단조롭게 완결되는 이야기이든, 끝내 답을 얻지 못하고 종지하는 교향곡이든 만족하지 못했는데 말이다. 그가 보여주는 자신의 작곡 과정을 통해, 우리는 작품 속 진정한 베토벤의 모습을 아주 가까이에서 확인할 수 있다. 물론 여기서도 성급한 판단을 경계해야 한다. 자신의 마지막 현악 4중주인 16번에 “그래야만 할까? 그래야만 한다”(Muss es Sein? Es muss Sein!)고 메모를 휘갈길 당시, 그는 실존주의적 중재에 빠져 있었을까? 아니면 작법에 대한 자문이었을까? 베토벤에 관해서 라면 종종 그렇듯, 가능성은 양쪽 모두를 가리킨다.

루돌프 대공

‘호(好)’보다 ‘불호(不好)’

악보 연구 외에도 나는 반(反)직관적 요소를 작업에 추가했다. 베토벤이 했던 일을 살펴보는 대신, 그가 하지 않았던 일을 목록으로 작성한 것이다. 가령, 그는 한 번도 교회에 간 적이 없다. 신성 로마 제국의 수도에서 베토벤은 국교를 따르는 사회적 의식을 피했다. 예술가라는 지위로 그저 단순하게 빠져나갈 수 있었다. 그러면서도 그는 사적인 신앙에 관해 입장을 내비치기도 했다. 제시간에 작업을 완료하기로 유명한 그가 용서할 수 없을 정도로 늦게, 심지어 3년이나 늦게 결과물을 전달했던 일화에서 알 수 있다. 친구 루돌프 대공의 독일 올뮈츠 대주교 서품을 위해 작곡한 ‘장엄미사’가 바로 그 작업이다. 뇌전증에 걸렸고 동성애자라는 소문이 있었던 루돌프는 베토벤의 절친한 친우였고, 그는 친우를 신에게 빼앗기는 것을 싫어했다.

베토벤이 결코 독주곡을 쓰지 않은 현악기가 하나 있다. 그는 바이올린 소나타와 첼로 소나타를 작곡했지만, 비올라만은 절대 손대지 않았다. 비올라는 베토벤이 14세의 나이로 본에서 처음 급여를 받으며 연주한 악기였고, 이로 인해 선제후의 관심을 받았으며, 돈을 모아 빈으로 가서 하이든에게 수학하는 기회를 얻었는데도 말이다. 고향을 떠난 그가 기교 넘치는 비올라 독주곡 몇 번만 해치우면 좀 더 편하게 살 수 있었을지 모른다. 하지만 베토벤은 편한 길로 가지 않는 사람이다. 비올라를 버림으로써 그는 잔인했던 유년기와 결별하고 빈에서 새로운 자아를 만들기로 결심한다. 그가 하지 않았던 일에 한 가지를 더하자면, 그는 본으로 돌아가지 않았다.

물론 그는 다른 어느 곳으로도 향하지 않았다. 의사의 지시에 따라 휴가 객들과 시간을 허비하다 대단히 비참해진 여름철 온천 여행을 제외한다면 말이다. 56년간의 긴 생애 동안 베토벤은 한 번도 바다를 본 적이 없다. 문명의 정점인 파리나 로마에 다녀온 적도 없다. 그는 금전적인 수익을 내며 대도시를 유랑하고 바다를 건넜던 하이든, 모차르트와는 다른행보를 보였다. 베토벤은 외곬의 삶, 그 자체를 살며 한순간도 낭비하는일이 없었다.

베토벤 교향곡 6번 ‘전원’ 자필 악보

사랑도 사치였다

그가 전혀 하지 않았던 일 중 또 하나는 성적 관계를 맺는 것이었다. 베토벤은 10대, 20대 후반, 40대 초, 사교계에 막 데뷔한 젊고 어여쁜 여성들과 강박적인 사랑에 계속 빠지나, 그들은 그의 사랑을 가벼이 여겼고 더 발전하지 않았다. 그들은 부유한 백작이나 왕자의 마음을 사로잡기 위해 사교계에 데뷔한 자들이었기에, 베토벤보다 사회적 지위가 두 계단은 높았다. 베토벤은 이룰 수가 없기에 이들을 선택한 것이다. 그는 창조적인 상상력의 원천인 낭만적인 사랑을 경험해야만 했지만, 신체적인 접촉으로부터 뒷걸음질 쳤으며 몸단장과 같이 스스로를 꾸미는 일도 전혀 하지 않았다. 사랑이 끝나면, 그가 느끼는 고통은 잠깐이었다. ‘불멸의 연인’에게 보내는 유명한 편지도 발송되지 않았다는 점에서 상당한 의미를 내포한다. 이 편지는 베토벤 사후 그의 서랍 안에서 미개봉인 상태로 발견됐다.

그 어떤 연인과도 잠자리를 갖지 않았다면, 혹시 매춘은 했을까? 첼리스트였던 니콜라우스 츠메스칼 백작이 매음굴에서 술자리를 하자며 유혹했을 때도 베토벤은 그런 ‘질척한 장소’에는 흥미가 없다는 말로 일축했다. 정신과 의사라면 이 대답에서 인지하겠지만, 현재로서 말할 수 있는 사실은 그가 성행위를 피했다는 것이다. 베토벤 사후 부검에서도 성병의 흔적은 찾을 수 없었다.

그가 이 모든 것을 삼갔던 복잡한 이유는 여러 가지겠지만, 행동 방식은 존경스러울 정도로 명백하다. 베토벤은 자신이 추구하는 목표와 관련 없거나 유해한 활동은 그것이 비올라든, 휴가든, 봉납물이든, 잠자리든 모두 차단해버렸다. 그의 성품에서 가장 위대한 강점은 원칙의 힘이자 거절하는능력에 있었다.

‘왜 베토벤인가’

‘왜 베토벤인가’

노먼 레브레히트 저(2023)

Oneworld Publications

번역 evener

노먼 레브레히트 칼럼의 영어 원문을 함께 제공합니다

본 원고는 본지의 편집 방향과 일치하지 않을 수 있습니다

Is it possible to be world famous all your life and yet remain completely unknown?

When Ludwig van Beethoven died on March 26, 1827, nobody knew what to say about him. He had a small handful of lifelong friends and a wider circle of musical acquaintances but not even the most fluent or self-advertising among his circle could find words to describe him. ‘Oh, the great man, the pity of it!’ is the general tenor of comment.

It fell to the national poet Franz Grillparzer to compose the graveside eulogy and he fell back mostly on poetic clich?. But in one stanza Grillparzer, who knew Beethoven from 1805 on, touched on the very reason that he eluded everyone: ‘He fled the world because he did not find, in the whole compass of his loving nature, a weapon with which to resist it. He withdrew from his fellow men after he had given them everything and had received nothing in return.’ This is harsh and not completely true, but Grillparzer is right in stating that Beethoven made himself deliberately unknowable, holding himself apart from the world so that its chatter did not distract him.

Unknowability is the assumption that every responsible biographer must accept. Those who try to draw character from incidents and anecdotes end up undone. Beethoven lays traps for pursuers; he is not what he seems. In my three-year quest I decided to proceed strictly through the music ? the hand on the page which, in these times, is often digitally visible online. Here, there are plenty of clues ? inspirations, erasures, second guesses. Why, for instance, does he strike out the movement titles in the Pastoral Symphony? He is unhappy about something ? either the over-simplistic storyline, or something in the symphony itself which he ends almost without resolution. When he shows us his reworkings, we come very close to seeing the real Beethoven at work.

Here too, however, we must beware of rapid diagnosis. When he scrawls ‘Must it be? It must be’ in his valedictory string quartet, is he engaged in existential mediation, or technical self-questioning? often with Beethoven, the signpost points both ways.

Aside from studying the music, I added a counterintuitive wrench to my toolkit. Instead of looking at what Beethoven did, I made a categorical list of the things that Beethoven did not do.

He never, for instance, went to church. In the capital of the Holy Roman Empire he abstained from the social rituals of the state religion. As an artist, Beethoven can get away with it ? just. But he is also making a statement about the privacy of faith. We see it once more when, meticulous in delivering commissions on time, he brings forth one work unforgivably late ? three years late, in fact. It is the Missa Solemnis, written for the ascendance of his friend Archduke Rudolf to the archbishop’s seat at Olm?tz. Epileptic and rumoured to be gay, Rudolf was Beethoven’s close confidant. He hated losing him to God.

There is one stringed instrument for which Beethoven never writes a solo. He turns out sonatas for violin and cello, but not a whisper for viola. Yet viola was the instrument that Beethoven, aged 14, played in order to obtain his first paid position in Bonn. It brought him to the ruler’s attention and helped raise funds to send him to Vienna to study with Haydn. Away from home, it would have been easy to knock off a couple of viola solos that would showcase his virtuosity. But this is Beethoven: he does not do easy. By abjuring the viola he is telling up of his determination to slam the door on his brutalized childhood and remake himself in Vienna. Add to the list of things he never did ? he never returned to Bonn.

Nor did he go pretty much anywhere else ? except, on doctor’s orders, to summer spas, where he dallied with holiday makers and made himself thoroughly miserable. In a long life of 56 years, he never saw the sea. Never visited Paris or Rome, summits of civilization. Haydn and Mozart profitably toured great capitals and crossed the sea. Not Beethoven. His was a life of single-minded dedication, not a moment to be wasted.

There is one other thing he never did, and that is have sexual relations. In his teens, late 20s and again as he turned 40, he fell in love repeatedly and obsessively with pretty young debutantes who toyed with his affections but made sure it went no further. They were two social classes above him, out to catch a rich count or a prince. Beethoven chose them for their unattainability. He needed to experience romantic love as a resource for his creative imagination but he recoiled from physical contact and did nothing (like washing) to make himself desirable. When love ends, his pain is brief. The famous letter to an ‘immortal beloved’ is most significant in that it was never sent. They found it unopened in a drawer when he died.

If he never bedded any of his beloveds, might he have paid for sex? A cello-playing official Nikolaus von Zmeskall tried to tempt him on a brothel crawl but the only response from Beethoven was that he had no interest in such ‘swampy places’, a phrase psychiatrists will recognise. So far as it is possible to tell, he avoids sexual intimacy. His autopsy is clear of venereal disease.

His reasons for all of these abstentions are numerous and complex but the pattern of conduct is admirably clear. When Beethoven decided an activity was extraneous or deleterious to his core purpose, he shut it down ? be it a viola, a vacation, a votive offering or a roll in the hay. The greatest strength of his character was its force of principle, his ability to say, No.

글 노먼 레브레히트

영국의 음악·문화 평론가이자 소설가. ‘텔레그래프’지, ‘스탠더즈’지 등 여러 매체에 기고해왔으며, 지금 이 순간에도 자신의 블로그(www.slippedisc.com)를 통해 음악계 뉴스를 발 빠르게 전한다