노먼 레브레히트 칼럼 | SINCE2012

영국의 평론가가 보내온 세계 음악계 동향

만민이여,

그대 모두 형제이니!

200번째 생일을 맞이한 베토벤 교향곡 9번을 다시 보다

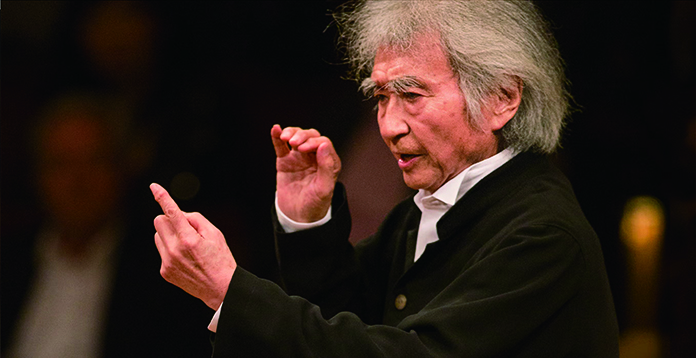

베토벤의 교향곡 9번 초연 며칠 전, 오스트리아 빈에서 개와 산책을 하던 이들은 뭔가 심상치 않은 점을 발견했다. 개들이 공연 포스터에 코를 대고 킁킁대자 사람들은 ‘피날레에 독창과 합창이 등장하는’ ‘장대한’ 새 교향곡에 대해 알게 됐다. 이는 교향곡이 오케스트라만의 것이라 정의하던 관습을 정면으로 배반하는 일이었다. 작곡가의 청각 장애가 이미 세간에 알려졌기에 ‘루트비히 판 베토벤이 지휘에 직접 참여한다’는 소식 역시 불안을 없애 주지는 못했다. 음악계의 ‘호의로’ 오케스트라와 합창은 대규모로 편성됐다. 교향곡은 지금까지와는 차원이 다르게 길 예정이었다.

그러나 가장 놀라운 점은 바로 공연 날짜였다. 날짜는 그 주 금요일인 1824년 5월 7일이었다.

금요일이라니. 아무도 가지 않을 것이라며 사람들은 경악했다. 집권 계층은 주말마다 시골 별장으로 향하는데, 당대 문화적 영향력을 행사했던 백작과 귀족 없이 신작을 발표해 봤자 아무 소용이 없을 것이었다. 베토벤은 저녁 시간의 공연장을 빌릴 수 있는 게 그날뿐이고, 이 교향곡이 지배 계층이 아닌 평범한 사람들에게 전해지길 원한다며 불퉁하게 설명했다. 그는 티켓 가격을 인하하고 그 자신이 검은색 프록코트가 없어 녹색 재킷을 입음으로써 드레스 코드 규칙도 깼다. 이 공연의 모든 면면에서 공고히 수립된 규율을 전복하겠다는 베토벤의 의도가 보였다.

두 세기 전, 초연의 그날

관객은 기쁜 마음으로 참석했으며, 중간에 2악장은 한 번 더 연주해 달라 요구했다. 공연이 궁금해 도시에 머물렀던 귀족 중 한 백작은 숨이 넘어갈 지경임에도 들것에 실려 나타났다. 좌석이 없는 학생들은 측면 난간에 매달렸다. 긴장이 50분 내내 계속 고조되다 피날레가 시작되고 6분 후, 베이스가 이렇게 외친다. “벗이여, 이런 음 말고 더 즐거운, 더 기쁜 걸 노래하세!” 가수가 숨을 고를 수 있게 오케스트라가 한 마디를 주고 나자, 그는 소리친다. “환희를(Freude)!”

이제 합창이 시작되고 “모든 인간은 형제가 된다”라는 구절로 변혁을 꾀한다. 신이 부여한 황제의 권리를 부정하므로 합창단이 체포될 수도 있었던 구호였다. 베토벤은 독일 시인 프리드리히 실러의 희망찬 1785년작 ‘환희의 송가’가 지닌 힘을 군중에게 부여했고, 이 힘은 이제 빈, 나아가 모든 지역의 기반을 뒤흔드는 정치적 힘이 됐다. 실러의 시는 희망적이고 이상적인데, 베토벤은 이를 실현 가능하고 필연적으로 재탄생시켰다. 관객은 동조의 함성을 내질렀고, 당대 공연장에서는 금지되었던 소음 너머로 경찰국장의 정숙하라는 외침이 들렸다. 독창자가 베토벤의 소매를 당겨 뒤돌게 해서 발을 구르며 환호하는 객석을 보여주자 그는 이렇게 말했다. “승리를 얻었으니, 나는 이제 진심을 말할 수 있다.”

쏟아져 온 찬사, 전 세계 문화를 바꾸다

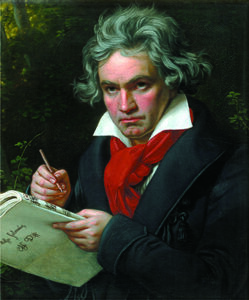

베토벤

그 순간부터 두 세기가 흐를 동안 교향곡 9번은 “지상의 환희에 대한 장엄 미사”라 표현한 카를 마르크스부터, 최근 클래식 FM에서 “현재의 영국 노동당을 잘 대변해 주는 작품”이라고 말한 노동당 대표 키어 스타머(1962~)에 이르기까지, 좌익의 모든 곳에서 사회 개혁가의 구호로 자리매김했다. 스타머는 다음과 같이 말한다. “교향곡 9번은 운명적이며 극도로 긍정적인데, 이는 노동당과 상당히 궤를 같이 합니다. 사람들을 한데 모으는 것인데, 베토벤은 이 작품으로 모든 이를 하나로 모았습니다. 더 나은 곳으로 전진하고자 하는 바로 그 마음으로 말이죠.”

이 교향곡은 사회의 다양한 가능성을 전달해 왔다. 구소련의 이오시프 스탈린은 모든 마을에서 이 곡을 재생하라 명령했으며, 독일의 아돌프 히틀러는 본인이 아끼는 지휘자 빌헬름 푸르트벵글러와 베를린필을 거대한 나치 하켄크로이츠 표식이 걸린 군수공장으로 보내 이를 연주하도록 했다. 일본에서는 매년 크리스마스 시즌 최대 만여 명의 아마추어 가수가 함께 교향곡 9번을 합창하는 기록적인 ‘다이쿠(第九)’ 공연이 열린다. 이란의 최고지도자 아야톨라는 2005년 교향곡 9번을 사회 통념에서 벗어나며 서구적이라는 이유로 금지했으며, 중국의 문화대혁명기의 공산당 지도자 4인방도 베토벤 전곡을 금지했었다.

로디지아(현 짐바브웨)의 백인 정권을 대표하던 이언 스미스는 ‘환희의 송가’를 국가(國歌)로 채택했다. 1985년 유럽 연합(EU) 역시 이를 공식 찬가로 지정했는데, ‘모든 인간은 형제가 된다’는 실러의 포용성에 대한 꿈이 EU 및 그 시민에게만 한하여 적용됐기 때문이다. 그 이외의 인류는 가시철조망 뒤에서 송환을 기다리며 대기하는 모습이지만 말이다. 독일 베를린 장벽이 무너질 때 레너드 번스타인은 그 승리를 기념하는 공연을 지휘하며 가사 ‘환희(Freude)’를 ‘자유(Freiheit)’로 바꿨다. 영국 작가 앤서니 버제스는 소설 ‘시계태엽 오렌지’에서 청소년 폭력배의 처방약으로 교향곡 9번을 사용한다. 이는 스탠리 큐브릭 감독의 1971년 동명의 영화에서 라파엘 쿠벨리크(1914~1996)의 사운드트랙으로 그 영향력이 증대되었다. 미국 페미니스트 음악학자인 수잔 맥클러리(1946~)는 베토벤의 이 중대한 명작에서 “강간범이 내뿜는 질식할 듯한 살의에서 풀려날 수 없는 감각”을 들었다. 그의 논문은 시인 아드리안 리치(1929~2012)가 ‘베토벤 교향곡 9번의 성적 함의와 이해’를 집필케 하였고, 여기서 시인은 “자아의 터널에서 나와 환희에 차 소리치는” 프로이트적인 구절을 적고 있으나 그 의미는 알 수가 없다. 보편성에 있어 가히 최고라 할 수 있는 베토벤은 어떤 해석에도 열려 있어, 음반은 가장 빠른 연주인 39분부터 가장 느린 연주인 105분까지 존재한다. 그러나 둘 다 터무니없기는 마찬가지이다. 그 중간이 맞는 것 같다.

아직도 우리가 ‘환희’하는 이유

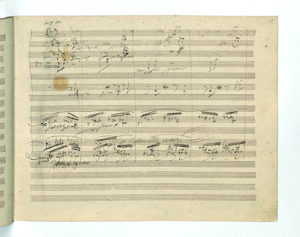

베토벤 교향곡 9번 초고

그렇다면 우리가 알고 있는 베토벤의 의도는 무엇일까? 당시 오스트리아인 남성 평균 수명이 35세 미만임을 고려할 때 53세였던 그는 훨씬 장수했고, 빚더미에 앉아 런던 필하모닉으로부터 표준 이하 값으로 작품을 위촉받아 1823년 한 해를 교향곡 작곡을 위해 바쳤다. 8월이 끝나갈 무렵 악보에 적힌 곡은 총 15분밖에 되지 않았고, 느린 악장을 채우는 데는 두 달이 더 걸렸다. 통증과 고통에 시달렸던 베토벤은 독일 바덴에서 온천욕 치료 후 빈으로 돌아와 수기로 “알아냈다! 알아냈다!”라는 메모를 적었다.

1824년 2월, 교향곡 9번이 완성되었으나 베토벤은 의심을 품은 채 합창이 없는 새로운 피날레를 쓰는 것에 관해 이야기하며 “실수를 했다”라고 말했다. 베를린에서 초연한 뒤, 그는 런던에서의 계약에도 불구하고 이 작품을 프로이센 국왕에게 헌정한다. 빈에서의 초연권은 지역 상류층의 파벌로 인해 결정됐는데, 이는 평등주의에 대한 베토벤의 헌신이 아주 절대적이지는 않았다는 점을 보여준다.

물론 그의 망설임이 ‘환희의 송가’가 지닌 본능적인 초월성을 지우지는 못한다. 스트라빈스키는 “절망적으로 지루하다”고 하고, 이언 매큐언은 “유치원에서 들을 수 있는 선율”이라 폄하했으나, 중세 돌림노래 ‘여름이 오다(Sumer Is Icumin In)’부터 오늘날 테일러 스위프트에 이르기까지 끈질기게 귓가에 맴돌고 숭고한 희망을 노래하는 곡조는 인류 역사상 몇 되지 않는다. 2박의 진행으로 전 세계가 다 함께 ‘환희의 송가’를 노래할 수 있다.

그 환희가 지금까지 지속되고 있다는 증거로 코로나19로 봉쇄가 시작된 2020년 3월의 첫날을 떠올려 보았다. 사람들이 함께 연주하는 것은 물론이고 다시 만날 수 있을지를 걱정하던 시기였다. 로테르담 필하모닉 오케스트라 단원들은 안전을 위해 격리된 방 안에서 영상 통화 플랫폼 ‘줌(Zoom)’으로 베토벤 교향곡 9번을 연주하기 시작했다. 팬들에 의해 편집되어 유튜브에 게시된 이 동영상은 며칠 만에 300만 조회수를 기록하며 온라인에서 가장 빠르게 순위에 오른 클래식 음악 영상이 되었다. 오래된 네덜란드 맥주 회사의 광고를 인용하자면, 베토벤은 다른 작곡가가 가닿을 수 없는 영역에 활력을 불어넣었다.

영국 길드홀 음악 연극 학교 출신인 키어 스타머가 2024년 노동당의 정권 탈환을 영국 땅에 선사한다면, 수백만 명에게 교향곡 9번의 호소를 인용해 “이 입맞춤을 전 세계에” 전한다고 말할 수도 있을 테다. 베토벤은 자신의 아홉 번째 교향곡이 불평등을 없애기를 바랐다. 작품이 세상에 나온 지 3세기에 들어서는 지금, 이 교향곡은 거부할 수 없는 매력을 여전히 간직하고 있다.

번역 evener

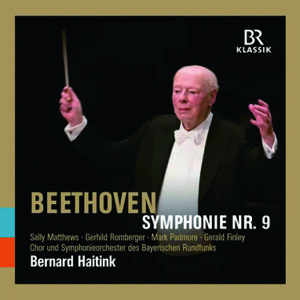

베토벤 교향곡 9번 노먼의 추천 음반은?

베르나르트 하이팅크/ 바이에른 방송교향악단(2019)

BR Klassik 900180

빌헬름 푸르트벵글러/ 베를린 필하모닉(1942)

Archipel Records ARPCD0270

프리처이 페렌츠/ 베를린 방송교향악단(1957)

DG E4636262

라파엘 쿠벨리크/ 바이에른 방송교향악단(1975)

Orfeo C207891B

데이비드 진먼/취리히 톤할레 오케스트라(1999)

Sony 88843077922

로테르담 필하모닉(2020)

노먼 레브레히트 칼럼의 영어 원문을 함께 제공합니다

본 원고는 본지의 편집 방향과 일치하지 않을 수 있습니다

Beethoven’s ninth symphony at 200 years old

A few days before the premiere of Beethoven’s ninth symphony, dog walkers in Vienna realized nothing was ever going to be the same again. As their pooches sniffed a concert placard, the owners learned about a ‘grand’ new symphony with ‘solo and chorus voices entering in the finale’, a massive breach with tradition which defined the symphony for orchestra alone. The announcement that ‘Herr Ludwig van Beethoven will himself participate in the direction’ was hardly reassuring, given the composer’s well-known deafness. The orchestra and chorus were to be supersized ‘as a favour’ by music societies. The symphony would be long, the longest ever heard.

But the most shocking detail was the date. The concert was that same week, May 7, 1824.

A Friday? people cried. No-one will come. The ruling classes go to their country houses at weekends and there’s no point putting on a new work without counts and princes, the cultural influencers of those days. Beethoven gruffly explained that this was the only night he could get the theatre and anyway he wanted this symphony to be heard by real people, not just the elite. He cut ticket prices and broke dress code, wearing a green jacket because he did not own a black frock coat. Everything about this occasion declared his intention to subvert the established order.

The audience was up for it, demanding a repeat of the second movement. Some aristos had stayed in town; one old count was stretchered in from his deathbed. Seatless students clung to the side-rails. The tension cranked up over fifty minutes. Six minutes into the finale, a bass singer declared, ‘Friends, not these notes – let’s try something nicer, more cheerful’. The orchestra gave him one bar to catch his breath before the bass bellowed out ‘Freude!’, for joy.

The chorus rose, invoking revolution with the words ‘alle Menschen werden Brüder’ – all people should be brothers – a slogan that could have got them arrested for denying the God-given rights of emperors. Beethoven had given crowd power to Friedrich Schiller’s wishful Ode to Joy of 1785. It was now a political force, threatening the foundations of the state, of all states. Schiller’s poem had been wishful, utopian; Beethoven made it seem practical, inevitable. The audience roared approval. A police commissioner was heard shouting for order above the musical din. A soloist plucked Beethoven’s sleeve to show the composer his cheering, foot-stamping audience. ‘My triumph is attained,’ he said, ‘from now I can speak from the heart.’

From that moment on, through the next two centuries, Beethoven’s ninth symphony has been a rallying cry for social reformers of every shade of red from Karl Marx, who described it as ‘a solemn mass of earthly joy’, to Keir Starmer who recently told Classic FM that this symphony best summed up the British Labour Party under his leadership: ‘It has got a sense of destiny and is hugely optimistic. This is very sort of Labour. You’re getting everybody, Beethoven’s getting everybody onto the stage for this…. it’s that sense of moving forward to a better place.’

The symphony has served many visions of society. There was Joseph Stalin who ordered it to be played in every Soviet village and Adolf Hitler who sent his favourite orchestra and conductor, the Berlin Philharmonic with Wilhelm Furtwängler, to bang it out in munitions factories beneath a giant swastika. Every year around Christmas the Japanese put on record-breaking ‘Daiku’ concerts of the Ninth with up to ten thousand amateur singers in the chorus. In Iran the Ayatollahs banned the symphony in 2005 as ‘indecent and western’; China’s Gang of Four banned Beethoven altogether.

Ian Smith’s white-rule regime in Rhodesia adopted the Ode for Joy as a national anthem. So did the European Union in 1985, interpreting Schiller’s inclusivity dream that ‘all people should be brothers’ to be applicable only to EU member states and their citizens. The rest of humanity can be held behind barbed wire, pending repatriation. In Berlin, when the Wall came down, Leonard Bernstein conducted a triumphalist concert in which he replaced the noun ‘Freude’ with ‘Freiheit’ – freedom.

The novelist Anthony Burgess used the symphony as a young thug’s drug of choice in A Clockwork Orange, its impact amplified in Rafael Kubelik’s soundtrack performance on Stanley Kubrick’s 1971 film. A feminist musicologist, Susan McClary, heard ‘the throttling murderous rage of a rapist incapable of attaining release’ in Beethoven’s climactic masterpiece. Her thesis prompted the poet Adrienne Rich to write ‘The Ninth Symphony of Beethoven Understood At Last As A Sexual Message’, which contains the Freidian line ‘yelling at Joy from the tunnel of the ego’, whatever that might mean. Beethoven, at his most universalist, was open to every kind of interpretation. The fastest recording is 39 minutes, the slowest 105, both irrational. Midway is about right.

What, then, do we know of Beethoven’s intentions? He was 53 years old, very old indeed by Austrian reckoning where average male life expectancy was below 35. Deep in debt, he accepted a below-par commission from the Philharmonic of London and set aside the year 1823 to compose the symphony. By the end of August, he had only 15 minutes of music on paper. The slow movement took him two months more. Beset by aches and pains he took a spa cure in Baden, returning to Vienna with a notebook in hand crying ‘I have it! I have it!’

The score was signed off in February 1824 but Beethoven, having doubts, talked of writing a new finale without voices. ‘I made a mistake,’ he said. He offered the premiere to Berlin and a dedication, despite his London contract, to the Prussian Emperor. First night rights were won for Vienna by a cabal of local toffs, indicating that Beethoven’s commitment to egalitarianism was not altogether unequivocal.

Not that his hesitations in any way diminish the instinctual transcendence of the Ode to Joy. Igor Stravinsky might scorn the melody as ‘hopelessly banal’ and Ian McEwan as ‘a nursery tune’, but few jingles in human history from ‘Sumer is icumin in’ to the latest Taylor Swift have the same ear-worm durability or spiritual uplift. Two beats in, the whole world sings along to the Ode to Joy.

For testimony of its lasting relevance I think of the first days of Covid lockdown in March 2020 when people wondered if they would ever meet again, let alone make music together. Members of the Rotterdam Philharmonic Orchestra, in solitary bedrooms, began to play Beethoven’s Ode on Zoom to save their sanity. Edited by geeks and posted on Youtube, the resultant video topped three million views in a matter of days, the fastest moving piece of classical music ever seen on the internet. Beethoven, to quote an old ad for Dutch beer, refreshes the parts other composers cannot reach.

So if the ex-Guildhall music scholar Keir Starmer brings the Labour Party back to power in 2024, he may well quote the symphony’s appeal to many millions, ‘this kiss to all the world’. Beethoven wanted his ninth symphony to erase inequality. Entering its third century, the symphony has lost none of its irresistible appeal.

글 노먼 레브레히트 영국의 음악·문화 평론가이자 소설가. ‘텔레그래프’지, ‘스탠더즈’지 등 여러 매체에 기고해왔으며, 지금 이 순간에도 자신의 블로그(www.slippedisc.com)를 통해 음악계 뉴스를 발 빠르게 전한다