노먼 레브레히트 칼럼 \ SINCE 2012

영국의 평론가가 보내온 세계 음악계 동향

전쟁의 악몽 속 음악

예술의 순기능을 실천하는 이들

라하브 샤니와 이스라엘 필하모닉 ©Luis Luque

이스라엘-하마스 전쟁으로 잠 못 이루던 밤, 나는 펼쳐진 두려움 속에서 즉흥적으로 연주를 했던 음악가들에 관해 생각했다. 하마스 학살 후 일주일이 지난 뒤, 이스라엘 필하모닉 오케스트라 단원들은 소규모 앙상블로 여러 병원을 돌아다니며 부상자, 의료진, 방문객을 위해 복도에서 연주를 했다. 이들을 보고 놀란 사람은 아무도 없었다.

역사를 거슬러 올라가 보면, 1948년 아랍-이스라엘 전쟁으로 인한 트라우마의 시기에도 음악가들이 나타나 위안을 주리라는 기대가 있었다. 작은 오케스트라와 함께 사막에서 피아노 연주를 하는 레너드 번스타인의 흑백 사진이 이를 증명한다. 1967년 제3차 중동 전쟁 당시, 다니엘 바렌보임은 도의적 원조를 전했으며 번스타인은 예루살렘 올리브 산에서 말러의 ‘부활’을 지휘했다. 1973년 제4차 중동 전쟁 때 레너드 코언은 탱크 사단과 함께 야영을 하기도 했다.

위로를 위해 폐허로 가는 세계의 연주자

브로니스와프 후베르만

아르투로 토스카니니

이번 전쟁에서 미사일 세례가 무력화되어 도시의 공연 재개가 허용되자마자 이스라엘필은 의상을 갖춰 돌아왔고, 관객은 공연장으로 밀려들었으며, 연대를 결심한 마에스트로들이 비행해 왔다. 체코 필하모닉의 세묜 비치코프(1952~)는 이스라엘 국가(國歌) ‘희망(Hatikvah)’을 지휘하며 눈물을 흘렸고, 취리히 오페라 총감독 자난드레아 노세다(1964~)는 관계자들이 놀라움과 경외감을 내뿜을 만큼 공중에서 멈춘 듯한 음표로 세상에서 가장 느린 ‘희망’을 지휘했다. 이고르 레비트(1987~)는 공항에서 바로 병원으로 이동해 훼손된 피아노를 연주했으며, 막심 벤게로프(1974~)는 자신의 스트라디바리우스 바이올린을 꺼내 들었다.

한 대학교 현악 4중주단은 이스라엘 텔아비브 미술관에서 현대음악을 연주했다. 이들의 단장은 가자 지구 터널에서 인질로 잡혔던 조카로 인해 비통함에 젖어 있었다. 음악가들은 자신이 경험한 유례없는 강렬함에 대해 내게 알려왔다. 어느 라디오 진행자는 다급하게 전화해 베토벤의 후기 작품들이 위안의 곡으로 어떤지에 관한 논의를 요구하기도 했다. 국가가 존재하기 전부터 그렇듯, 이 위기 속에서 음악은 필수적으로 느껴졌다.

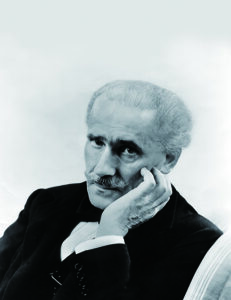

텔아비브에서 첫 번째 오케스트라 공연은 1936년 12월 26일 열렸다. 히틀러의 명령으로 인해 독일 관현악단에서 쫓겨난 유대인 연주자들로 구성된 공연이었다. 이내 오스트리아, 체코, 폴란드에서 온 난민이 합류했다. 이 오케스트라는 폴란드 바이올리니스트 브로니스와프 후베르만(1882~1947)이 고안한 것으로, 그는 아르투로 토스카니니가 팔레스타인을 방문하도록 이끄는 데에 성공한 사람이었다. 이때는 영국 정부가 아랍 폭동 사태가 가장 격렬하다고 일컬은 시기였으니, 양쪽 모두에게 위험이 도사리고 있었다.

토스카니니는 파시즘 피해자들을 지지하는 데에 열성적이었으나, 리허설에서 악단을 무정하게 다뤘던 완벽주의자이기도 했다. 그런 그가 터전과 재산, 활기마저 잃은 엉망진창의 난민 무리에 어떻게 반응했을지는 정확히 알 수 없으나, 밝혀진 바로는 매우 감정 이입한 나머지 다음 해에 자신의 안전을 보장할 수 없다는 영국 정부의 경고에도 불구하고 다시 텔아비브로 돌아갔다고 한다. 내가 가장 좋아하는 초창기 목격담은 텔아비브에서 예루살렘으로 향하는 길목에서 쏟아진 폭우에 발목을 잡힌 토스카니니와 후베르만에 관한 것이다. 키부츠(이스라엘 생활 공동체)의 천막이 모여있는 곳에 도달한 이들은 양철 지붕 구조의 공용 식당에서 비를 피했다. 토스카니니가 막사에서 커피를 마시고 있다는 말이 돌자 푸른 작업복 차림의 키부츠 일원들은 그를 둘러싸고 독일어로 브람스 교향곡 1번과 베를리오즈의 ‘환상 교향곡’의 메트로놈 표시에 대해 물었다. 토스카니니는 후에 웃으며 이렇게 회상했다. “굉장한 국가였습니다, 소작농들마저 음악을 알더군요.”

위기 속 연대로 뜻을 전하는 이스라엘 연주자

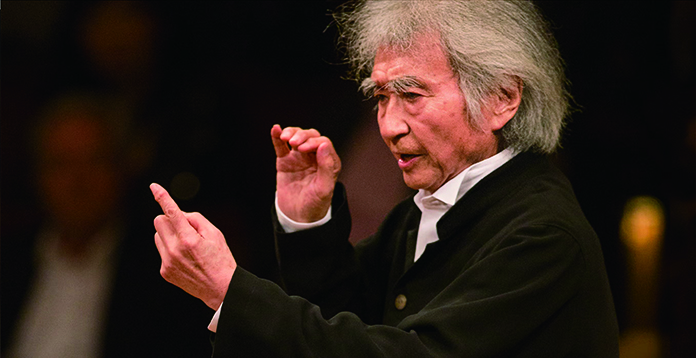

이스라엘필은 키부츠를 바탕으로 일류 국제 앙상블로 발전했다. 모든 연주자가 동등한 권리를 지녔으며, 악단의 상황을 확인하고픈 단원이 있으면 ‘사무국장’으로 알려진 매니저는 그들을 위해 장부를 펼쳐 주어야만 했다. 1977년 인도 출신의 주빈 메타가 음악감독직을 맡기 전까지 악단은 여러 지휘자를 순회했다. 주빈 메타는 수십 년간 단원들에게 활기를 불어넣었으며, 2020년 이스라엘 출신의 제자 라하브 샤니(1989~)에게 그 자리를 넘겨주었다.

이민 행렬은 악단의 소리와 사고방식을 바꾸어 놓았다. 늘 호전적이었던 이스라엘필은 1980년대 즈음에 러시아인들이 줄지어 현악 파트를 점령하면서 특히 다루기 힘들었으나, 이들은 이제 예루살렘과 텔아비브 음악원에서 수학한 토박이 연주자 세대에 자리를 내줬다. 이들 중 상당수가 새 음악감독인 라하브 샤니의 동급생이다. 분위기는 더 돈독해졌고 날카로움은 덜해졌으며, 오랜 시간 자리를 지켰던 사무국장 아비 쇼사니가 최근 은퇴를 하며 이러한 흐름이 더욱 공고해졌다. 연주는 한결 날래지고 자신감은 당연한 명분을 얻었다. 다만 변명의 여지없이 계속된 한 가지 결점이 있다. 바로 이스라엘필이 아직 아랍인 음악가에게 자리를 내준 적이 없다는 사실이다.

3대에 걸쳐 부모가 자식에게 좌석을 대물림하던 관객층은 미국의 클래식 음악 관객과 몹시 비슷한 차원으로 줄어들었다. 하지만 전쟁이 일어나면 대중은 실황 음악이 필요하다고 떠올리게 된다. 이는 비단 국영 오케스트라에게만 해당되지 않는다. 예루살렘 심포니는 지난 2월 예루살렘에서 말러 교향곡 7번을 연주했으며, 이스라엘 베르셰바 신포니에타는 가자 지구 최전방에서 베토벤을 연주하고 있다.

이 모든 일은 회피 행위도 현실 도피도 아니다. 이스라엘 오페라단은 2012년 제작된 도니체티의 ‘람메르무어의 루치아’를 최근 재공연했는데, 이 극은 피에 젖은 흰 가운 차림의 루치아가 신랑을 살인하는 광란의 장면에서 절정에 이른다. 이스라엘 사람이라면 가자 지구에서 음악 축제 중 젊은 여성들이 하마스 강간범들에게 잡혀가 피로 물들었던 사건과의 연관성을 금세 눈치챘을 것이다.

루치아를 보고 놀란 탄식은 있으되 항의는 없었다. 이스라엘 출신 소프라노 힐라 파흐미 루스친은 굉장한 박수갈채를 받았고, 키부츠 학교 졸업생인 오메르 벤 세디아 감독(Revival Director)은 이스라엘 방위군의 여성 관측 부대에 이 작품을 헌정했다. 부대는 이전에 하마스의 공격 계획을 상부에 경고했으나 무시당했고, 결국 윗선의 오만으로 인해 민간인의 피가 흩뿌려졌다. 도니체티 오페라의 모든 면이 사적이고 친밀한 느낌을 주어 많은 관객이 눈물을 흘렸다.

전쟁의 결과는 확실치 않지만 한 가지 확실한 점은 있다. 나는 이스라엘의 음악가와 음악 애호가 양쪽으로부터 서로를 향한 유대감이 부활했으며, 음악은 사치품이 아닌 실존을 위한 필수품으로 인식된다는 말을 들었다. 이스라엘과 가자 지구의 악몽 같은 시간을 견딜 필요가 없는 전 세계의 나머지 인류는, 삶이 위태로운 시기에 음악이 우리에게 무엇을 해줄 수 있는지에 관해 생각해 봐야만 한다.

번역 evener

노먼 레브레히트 칼럼의 영어 원문을 함께 제공합니다

본 원고는 본지의 편집 방향과 일치하지 않을 수 있습니다

In sleepless nights of the Gaza war I think about the musicians, improvising in the unfolding awfulness. A week or so after the Hamas massacres, members of the Israel Philharmonic toured hospitals in small ensembles, playing in corridors for casualties, medical staff and visitors. No-one was surprised to see them. There are expectations, going back to 1948 that in times of trauma, musicians turn up to provide relief. Grainy photographs exist of Leonard Bernstein playing piano in the desert with a small orchestra. In 1967 Daniel Barenboim brought moral support and Bernstein conducted Mahler’s Resurrection on the Mount of Olives. In 1973, Leonard Cohen camped out with a tank division.

This war, as soon as neutralized missile barrages permitted the resumption of city concerts, the Israel Phil was back in tie and tails and the audience surged to its halls. Maestros flew in, determined to show solidarity. Semyon Bychkov of the Czech Philharmonic conducted Hatikvah, the national anthem, with tears streaking his cheeks. Gianandrea Noseda of Zurich Opera led the slowest Hatikvah anyone can remember, notes frozen in mid-air as participants exhaled in shock and awe. Igor Levit went straight from the airport to a hospital to play a banged-up piano. Maxim Vengerov brought his Stradivarius.

A university string quartet played contemporary music at the Tel Aviv Museum, its leader grieving for her niece, held hostage in a Gaza tunnel. Musicians messaged me about the unparallelled intensity of their experience. A radio host called, urgently requiring a discussion of late Beethoven as light relief. Music has felt essential in this crisis, as it has done since the pre-dawn of nationhood.

The first orchestral concert was given in Tel Aviv on December26, 1936, its players consisting of Jews sacked from German orchestras by Hitler’s decrees. They were soon joined by Austrian, Czech and Polish refugees. The orchestra was the brainchild of the Polish violinist Bronislaw Huberman, who succeeded in charming Arturo Toscanini to visit Palestine in the thick of what British officials called ‘the Arab riots’. It was a calculated risk on both sides.

Toscanini, eager to support victims of fascism, was a perfectionist who brutalized musicians in rehearsal. How he would respond to a ragged band of fugitives, dispossessed and depressed, was unknown. The empathy, it turned out, was spontaneous, so much so that Toscanini returned the following year despite British warnings that his safety could not be guaranteed.

My favourite eye-witness story of these beginnings concerns Toscanini and Huberman, caught by a torrential downpour on the road from Tel Aviv to Jerusalem. Turning off into a tented kibbutz, they took shelter in the only tin-roofed structure, the communal dining hall. Word flashed round that Toscanini was drinking coffee in the hut and kibbutzniks in blue overalls came besieging him with questions in German about metronome markings in Brahms’s first symphony and Berlioz’s Fantastique. “Extraordinary country,’ beamed Toscanini. ‘Even the peasants know music.”

The philharmonic evolved into a high-class international ensemble, run on kibbutz lines. Every player had equal rights and the manager, known as the ‘secretary’ had to open the books on demand to any member who wanted to see what was going on. Conductors were peripatetic until, in 1977, the title of music director was granted to an Indian, Zubin Mehta, who had galvanized the musicians for a decade. Mehta finally yielded the title in 2020 to an Israeli-born protégé, Lahav Shani.

Waves of immigration changed the orchestra’s sound and attitude. Always combative, the IPO became recalcitrant in the 1980s when a wave of Russians overwhelmed the string sections. That wave has now given way to a generation of indigenous players, conservatory-trained in Jerusalem and Tel Aviv, many of them classmates of the new music director. The atmosphere is friendlier now, less paranoid, a shift exemplified by the recent retirement of the long-serving secretary-general Avi Shoshani. The playing is fleeter, the self-confidence more justified. One perpetual flaw, however, cannot be excused: the Israel Philharmonic has yet to admit its first Arab musician.

The subscription audience, which used to bequeath seats from parent to child down three generations, has thinned out in much the same dimensions as classical attendances in the US. But all it takes is a war and the public is reminded of its need for live music. And not just from the national flag-carrier. The Jerusalem Symphony has a Mahler Seventh this month and the Beer Sheva Sinfonietta, on the Gaza frontline, is playing Beethoven.

None of this is displacement activity, or escapist. The Israel Opera has revived a 2012 production of Donizetti’s Lucia di Lammermoor, culminating in a mad scene where Lucia appears in a blood-soaked white gown, having murdered her bridegroom. Israelis were quick to spot affinities with the blood-soaked young women dragged by Hamas rapists from a dance festival to captivity in Gaza.

There were gasps at Lucia, but no protests. The Israel-born soprano Hila Fahmi Ruschin received loud ovations and the director, Omer Ben-Seadia, a kibbutz school graduate, dedicated the work to an IDF women’s observation unit that warned of the Hamas attack plans and were ignored, paying with their blood for the dismissiveness of top brass. Everything about Donizetti’s opera felt personal and close; many spectators left in tears.

War outcomes are uncertain, with one exception. I hear from both musicians and music lovers in Israel of a renewal of the bond between performers and public, of a recognition that music is not a luxury but an existential need. Without having to endure the nightmares of Israel and Gaza, the rest of the world needs to be reminded of what music can do for us when life itself is on the line.

글 노먼 레브레히트

영국의 음악·문화 평론가이자 소설가. ‘텔레그래프’지, ‘스탠더즈’지 등 여러 매체에 기고해왔으며, 지금 이 순간에도 자신의 블로그(www.slippedisc.com)를 통해 음악계 뉴스를 발 빠르게 전한다