패배의 한숨으로 얼룩진 분열된 도시, 황혼이 내리다

그렇게 또 하루가 가고, 키프로스 섬은 재결합과는 거리가 멀어졌다. 섬의 북부는 39년 전 터키군에 의해 점령되었다. 20만 명의 그리스인들을 쫓겨났고, 세계의 이목을 피해 어떻게든 불법점거는 영속화됐다. 한편 그리스령 키프로스는 올해 두 번째 재앙, 즉 시민들의 노후 저축자금을 바닥내고 경기침체를 유발한 유럽 은행의 습격을 맞았다. 내가 여기 키프로스에서 참석하고 있는 파로스 체임버 페스티벌은 연주자들의 무료 연주, 러시아 은행의 비용 지불이 있어 가능했다. 최전선의 황량한 거리 위, 옛 구두 공장이 은밀히 공연장으로 개조되었다. 객석은 경기장 형식의 반원 형태로 연주자 위를 둘러싼다. 어딘가에서 가져온 의자들이 추가로 배치돼 공연장에 가득 찼으며, 표를 얻지 못한 백여 명의 사람들은 공연장 문 앞에서 돌아가야 했다. 키프로서의 니코시아에서는 독특한 혈통으로 회자되는 피아니스트의 데뷔가 있었다. 대단한 저녁이었다.

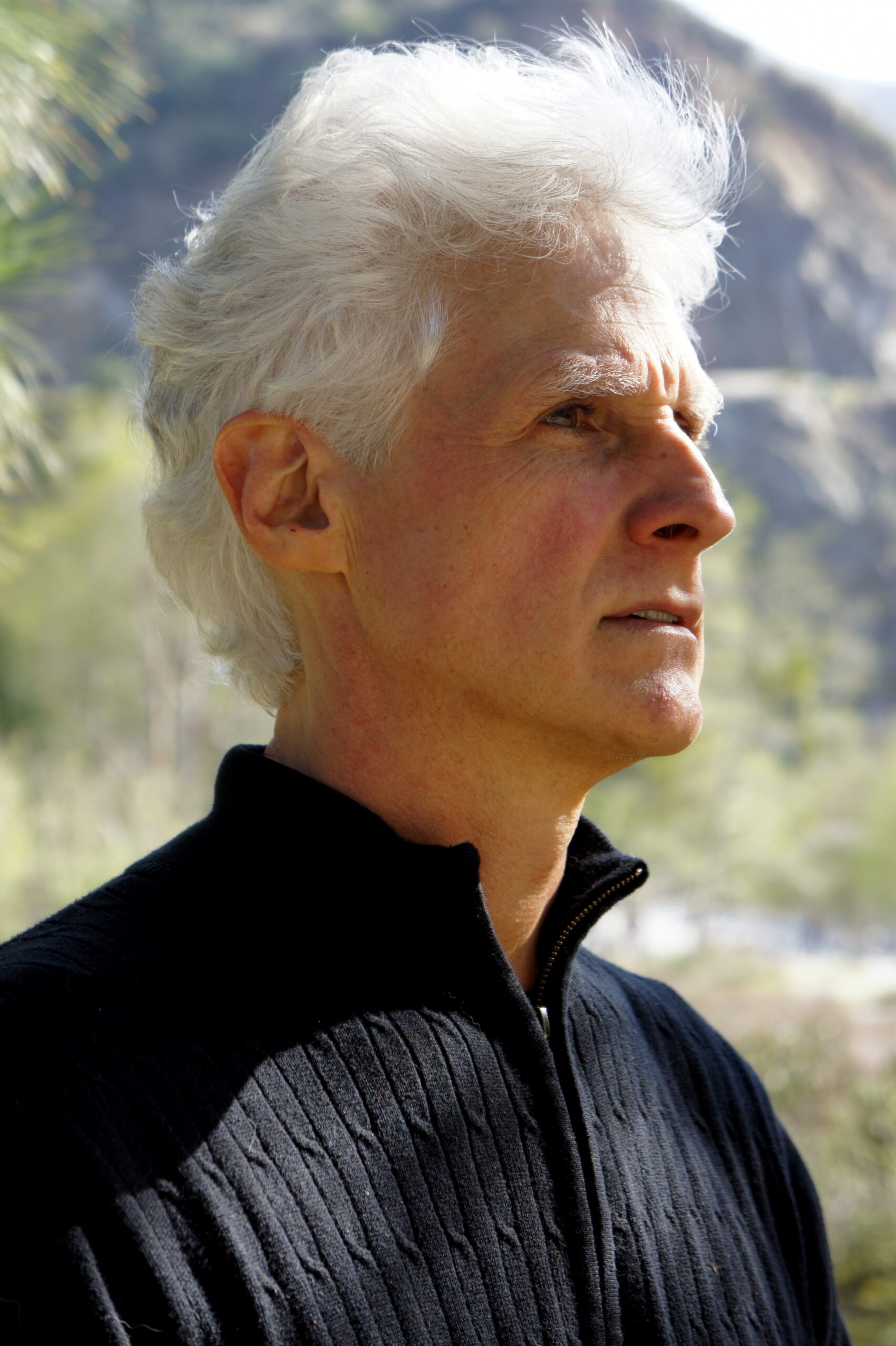

올해 41세인 엘리샤 아바스. 그는, 스스로를 구세주라 믿었고 1915년 정체불명의 벌레로 인해 사망한, 다섯 곡의 교향곡과 끝나지 않는 드라마를 남긴 신비주의 러시아 작곡가 알렉산드르 스크랴빈의 후손이다. 스크랴빈의 큰딸인 아드리아나는 프랑스로 이주해서 유대교로 개종하고 나치에 대항하는 유대인 군이 되어 싸우다 1944년 매복 중 총에 맞아 숨졌다. 그녀는 엘리샤 아바스의 외증조모다.

그러나 그의 가족사는 개인적인 이야기 앞에서 무색해진다. 네 형제 가운데 엘리샤는 특별한 재능이 있었다고 한다. 레너드 번스타인이 그를 받아들였고, 아이작 스턴은 그를 뉴욕으로 초대했으며, 아르투르 루빈스타인은 엘리샤의 빛나는 미래를 예견했다. 엘리샤의 아버지 슐로모는 예루살렘에서 일을 그만두고 까다로운 선생인 피아니스트 프니나 잘츠만과 가까운 위치의 호드하샤론으로 가족들과 이주했다. 슐로모는 아동도서 베스트셀러 작가로서 이스라엘에서 두 번째 인생을 개척하며 10년 동안 직접 엘리샤를 레슨에 데려갔다. 레슨 후 슐로모는 엘리샤가 공을 찰 수 있게 공원으로 데려갔다. 어느 날, 엘리샤는 더 이상 피아니스트가 되고 싶지 않다고 말했다. 그는 프로 축구선수가 되고 싶었다. “나는 속물근성이나 기대감 등 음악회를 둘러싼 분위기가 너무 싫었다. 선생님은 음악회에서 연주해달라는 부탁을 받았을 때와 그 연주가 취소되었을 때, 두 종류의 행복이 있다고 했다. 그녀가 옳았다.”

10대 후반과 20대에 걸쳐 엘리샤 아바스는 예루살렘 프리미어 리그에서 축구를 했다. 그는 미래의 첼시 매니저인 아브람 그란트에 발탁되어 하포엘 페타 티크바 클럽과 계약했다. “아브람은 결코 내게 져주지 않았다”라며 그는 어깨를 으쓱했다. 후보선수로 한 시즌을 보낸 후 그는 하포엘 크파르 사바로 옮겼다. “스트라이커였지만 득점하지 못했다.” 그는 미드필더로 가용됐다. 그 후 갈릴리 아랍인, 기독교인과 무슬림으로 구성된 팀인 하포엘 나자레트의 오른쪽 수비수로 옮긴다. 엘리샤는 그들을 ‘나의 형제들’이라 부른다.

나자레트의 그 누구도 그가 클래식 음악가였다는 사실을 몰랐다. 만약 알았다 하더라도 무슨 상관인가. 매일의 연습과 매주 세간의 주목을 받는 고도의 공연이라는 편협한 일상의 음악계와 마찬가지로, 축구계는 매우 소모적이고 자족적이다. 두 번의 실수는 우리를 끝내버릴 수도 있다. 어떠한 상황에서나 숨을 곳은 없다.

엘리샤는 결혼했고, 정착했으며, 경기도 잘했다. 그러자 의구심은 시작되었다. 스포츠 인생이 끝나면 무엇을 할 것인가? 여가 시간에 그는 법률 학위를 얻기 위해 공부했다. 시간이 걸릴수록, 그는 더 큰 상실감을 느꼈다. 15년간의 침묵 후 어느 날 밤, 그는 옛 피아노 선생에게 전화를 했다. 자신 이전의 어떠한 천재들보다도 음악의 도가니에서 더욱 멀리 방황하다가, 엘리샤는 드디어 그의 길을 되찾기로 결정한 것이다. “나는 프니나에게 밤 열한 시에 전화를 했다. 이야기를 좀 하고 싶다고 말했다. 그녀는 지금 바로 오라고 했다. 우리는 이야기를 나누었고, 차를 마시고, 담배를 피웠다. 나는 그 다음 무엇을 해야 할지 몰랐다.” 팔레스타인 태생의 프니나 잘츠만은 그녀가 아끼던 남자 형제가 독립전쟁 중 전사하자 자신의 커리어를 이스라엘로 제한했다. 프랑스 대가인 알프레드 코르토의 제자이자 콩쿠르 수상 경력이 있는 연주자로서, 그녀는 그 어떤 솔리스트보다 많은 협주곡을 이스라엘 필하모닉과 연주했다. 70대에는 국보이자 ‘이스라엘의 피아노 영부인’으로 불렸다. “나는 그녀와 데이트를 시작했다.” 엘리샤가 빙긋 웃으며 말한다. “나는 그녀와 영화를 보러 갔고, 음식점에 갔다. 우리는 이야기를 나눴다. 어느 날 저녁 그녀는 내게 텔하이로 오라 했다.” 텔하이는 갈릴리의 국제 하계 강좌이다. 그 개막 행사에서 엘리샤는 17세 학생이 차이콥스키 협주곡 Bb단조를 연주하는 것을 들었다. 완전히 매료되어 그녀와 산책을 나갔다. “그녀는 괴로움에 빠진 사람이었고, 남자 형제를 잃었다고 했다.” 두 사람은 밤새 꿈과 슬픔을 나누었다. “그녀의 방으로 가서 두 개의 침대에 머리를 대고 직각으로 누워 이야기하고 또 이야기했다. 아침이 되자 나는 그녀에게, 너는 나의 형제와 결혼하게 될 것이다, 라고 말했다. 정말 그랬고, 그들은 지금도 함께다.”

발견은 늘 눈앞에 있다. 구두 공장 공연에 모인 청중 가운데 이전에 그의 연주를 들었던 사람들은 거의 없다. 그는 무대로 성큼 들어와서 스타인웨이 그랜드 피아노에 앉아 의자 높이를 조절하고 성급하게(head-first) 쇼팽 마주르카 세트를 시작했다. 그가 건반에 집중한 것은 너무 가까웠으나, 말 그대로 ‘머리부터(head-first)’ 시작해 거의 팔뚝 정도의 거리에 있는 관객들조차 차단했다. 그는 스포츠 해설에서 말하듯이, 완전히 집중했다.

루빈스타인의 손끝에서 장난기 많고 애교 있는 소리로 탄생되었던 마주르카는 아주 진지한 인생 그 자체처럼 어둡고 불길하게 변했다. 세트가 끝나고 슈만을 치기 전, 엘리샤는 가까스로 박수를 인정하고, 그 이후에는 리스트 ‘시적이고 종교적인 선율’ 중 장송곡이 중단 없이 이어졌다. 그 우울한 작품이 거의 끝날 즈음 콘크리트 벽 너머 터키 모스크에서 기도 시간을 알리는 외침이 들려왔다. 대부분의 음악가라면 이 방해에 움찔했을 것이다. 그러나 너무도 깊이 집중한 엘리샤는 작품을 절정의 고요함으로 몰아갔고, 그의 얼굴은 무표정했다.

그를 우리가 알고 있는 그 어떤 피아니스트와도 비교할 수 없다. 단번에 사로잡는 매혹, 그리고 억제. 그는 관객을 집중시키기 위한 어떠한 명백한 노력을 하지 않았으나 내내 관객의 주의를 끌었다. 그는 음악에 어떠한 호화로움도 더하지 않았으나 그의 해석은 전적으로 개인적이고 때론 심오하다. 그는 갈채를 염두에 두지 않고 그 자신을 위해 연주하는 것 같다. 건반 앞으로 휘어져 음악에 푹 젖은 그를 보면, 득점 시 큰 환호성을 지르지만 매우 당황하며 수줍어하는 맨체스터 유나이티드의 미드필더 폴 스콜스가 떠오른다. 엘리샤 아바스도 비슷한 종류의 격렬한 거장의 과묵함을 나타낸다. 앙코르로 다시 무대에 나오면서 그는 잠시 관객 앞에 멈춰 섰다. 침묵은 길었다. 드디어 그가 입을 열었다. “좋은 저녁입니다.” 그게 다였다.

어느 날 밤, 엘리샤는 차 안에게 내게 말했다. “나는 성공을 원합니다. 그리고 그 꿈을 이루길 원합니다. 그러나 다른 사람들이 도달하는 방법으로는 하지 않을 겁니다. 나는 나 자신이어야 합니다.” 나는 그에게, 그는 다른 어떤 것이 될 수 없다고 말했다. 지난 두 세기 동안 조직화된 스포츠와 문화에서, 그 어떤 주요 인물도 한 쪽에서 다른 쪽으로 옮겨가고 다시 돌아온 적은 없었다. 엘리샤 아바스는 분리된 고기능의 두 형태 사이에 놓인 인간 가교이다. 최고 역량의 예술인으로서, 그는 발명과 배신, 성취와 절망의 가족사가 낳은 산물이다. 세계는 의식하지 못하지만, 피아노에서 그는 지성과 영성, 정신과 육체, 그리고 문질과 정치의 불균형을 통합하는 듯보인다. 악의와 고집으로 중간이 찢겨진 아프로디테의 섬에서 그는 상처를 치유할 음악의 힘을 잠시나마 보여준다.

번역 이윤희(인디애나 음대 박사)

Dusk falls on the divided city with a sigh of defeat

Another day has gone by and the island of Cyprus is no closer to reunion. The north was invaded by the Turkish army 39 years ago, driving out 200,000 Greeks and perpetuating an illegal occupation that somehow escapes the world’s attention. Greek Cyprus this year was hit by a second disaster, a Euro bank raid that drained the life savings of ordinary citizens and precipitated economic depression. The Pharos chamber music festival I am here to attend is going ahead only because the artists are playing for free and a Russian bank is paying the rent.

On a forlorn street that hugs the frontline, a former shoe factory has been privately converted into a recital space. Inside, the audience sits in a semi-circle, arena fashion, around and above the performers. The place is packed tonight, with extra chairs dragged in from other venues and more than a hundred ticketless customers turned away at the door. It’s a big night in Nicosia, the debut of a much-discussed pianist with a peculiar pedigree.

Elisha Abas, 41, is a descendant of Alexander Scriabin, the mystic Russian composer who believed he was the Messiah and died of a mystery bug in 1915, leaving behind five symphonies and a never-ending drama. Scriabin’s eldest daughter Ariadna moved to France, converted to Judaism, fought in an Armee Juive against the Nazis and was shot dead in an ambush in 1944; she was Elisha’s maternal great-grandmother.

The family history pales, however, beside his personal story. As a child of four, Elisha was told he had a unique talent. Leonard Bernstein embraced him, Isaac Stern invited him to New York, Arthur Rubinstein predicted a glittering future. Elisha’s father, Shlomo, gave up his job in Jerusalem to move the family to Hod Hasharon, close to the exacting teacher, Pnina Salzman. For ten years, Shlomo took Elisha to lessons, while developing a second life of his own as Israel’s best-selling children’s writer.

After lessons, Shlomo would take Elisha into the garden to kick a ball. One day, Elisha said he didn’t want to be a pianist any more. He was going to be a professional footballer. ‘I hated the atmosphere around concerts,’ he tells me,’ the snobbery, the expectation. My teacher used to say, there are two kinds of happiness. When you get asked to play a concert. And when it’s cancelled. She was right.’

Through his late teens and twenties, Elisha Abas played football in the Israeli premier league. He was signed for Hapoel Petah Tikvah by Avram Grant, future manager of Chelsea. ‘Avram never gave me a game,’ he shrugs. After a season in the reserves, he moved to Hapoel Kfar Saba. ‘I was a striker, but I never scored.’ They tried him in midfield. Then he moved as a right-back to Hapoel Nazareth, a team composed of Galileean Arabs, Christian and Moslem. ‘My brothers,’ Elisha calls them.

Nobody in Nazareth knew he had been a classical pianist. And, if they knew, who cared? Football society is as consuming and self-enclosed as the concert world, a blinkered routine of daily practice and weekly high performance in the public eye. Two failures can finish you off. In either pressure cooker, there is no place to hide.

Elisha married, settled down, played well. Then doubt set in. What would he do when the sporting life was over? In his spare time, he sat for a law degree. The longer it took, the more lost he felt. One night, after 15 years’ silence, he phoned his piano teacher. Having strayed further from the music crucible than any prodigy before him, Elisha had decided to find his way back. ‘I called Pnina at eleven o’clock at night,’ he relates. ‘And I said, I want to talk. She said, come round. Now. So we talked, drank tea, smoked cigarettes. I didn’t know what to do next.’

Salzman, Palestine-born, had confined her career to Israel after a beloved brother was killed in its war of independence. A prize-winning student of the French master Alfred Cortot, she played more concertos with the Israel Philharmonic than any other soloist and was known as ‘Israel’s first lady of the piano’, a national treasure in her 70s. ‘I started taking her on dates,’ grins Elisha. ‘I took her to the movies, to restaurants. We talked. One evening she said to me, come to Tel Hai.’

Tel Hai is an international summer course in the Galilee. At the opening event, Elisha heard a student, 17 years old, play the Tchaikovsky B-flat minor concerto. Smitten, he took her out for a walk. ‘She was a troubled person, her brother had died.’ All night long, they shared dreams and sorrows. ‘We went to her room and lay at right angles on two beds, head to head, talking, talking. In the morning I said to her, you are going to marry my brother. She did. They are together still today.’

We are about to find out. Few in the shoe factory have heard him play before. He strides into the room, sits at the Steinway grand, adjusts the stool and pitches head-first into a set of Chopin mazurkas – literally head-first, so close is his focus on the keyboard, shutting out the audience which is barely a forearm’s-length away. He is, as they say in sports commentary, in the zone. The mazurkas, which sounded winsome and playful in Rubinstein’s hands, turn dark and ominous, as deadly serious as life itself. When the set ends, Elisha barely acknowledges the applause before addressing a Schumann sequence, followed, without interruption, by the Liszt Funerailles. As that sombre piece nears fade-out, a muezzin shouts the call for evening prayers from the Turkish mosque just across the concrete wall. Most artists would flinch at the interruption. Elisha is so deep in the zone that his face remains impassive as he drives the piece to its climactic hush.

I cannot compare him to any pianist you will recognise. At once captivating and withholding, he makes no obvious attempt to engage the audience and yet grips the attention throughout. He imposes no flashiness on the music, yet his interpretation is altogether personal and, in places, profound. He plays, it appears, for himself, without regard for applause. The sole analogy that springs to mind, watching him coiled at the keyboard, immersed in his work, is of Paul Scholes, the ultra-shy Manchester United midfielder who, when he scored a goal would appear embarrassed by the fuss, eager to disappear. Elisha Abas represents a similar form of ferocious, virtuosic reticence. Called back for encores, he pauses to address the audience. The pause is a long one. Finally he says, ‘good evening’. And that’s it.

‘I want success,’ Elisha tells me, one night in the back of a car, ‘of course, I do. And I hope to achieve it. But I will not do what others do to get there. I must be myself.’ I tell him I don’t think he could be anything else. Never, in two centuries of organised sport and culture, has a major player crossed from one to the other, and back. Elisha Abas is a human bridge between two discrete forms of high performance. An artist of the highest calibre, he is the product of a family story of invention and betrayal, achievement and despair. At the piano, oblivious to the world, he seems to unite disparities of the cerebral and the spiritual, the spiritual and the physical, the physical and the political. On the island of Aphrodite, ripped down the middle by malice and obduracy, he gives a glimpse of the power of music to heal the gash within. NL