늦여름에 만난 브람스 음악의 축복

현장의 아쉬움을 달랜 두 음반, 하이팅크(런던 심포니)와 피셰르(덴마크 체임버)의 연주

팬데믹으로 두 해를 보내는 동안, 가장 그리웠던 작곡가는 요하네스 브람스였다. 다른 작곡가의 경우 음반이나 라디오, 온라인으로 적당히 만족하며 들을 수 있었지만, 브람스는 그 거리감을 용납하지 않았다. 그는 가장 물리적인 작곡가로, 음악적으로 온전한 몰입을 필요로 하는 ‘풍성하고 실재적인 기질을 지닌’ 인상적인 개성의 소유자이다. 간단히 말하자면, 브람스를 들으려면 현장에 있어야 한다.

요하네스 브람스(1833~1897)

브람스는 공연장 안에 존재한다. 오토 클렘페러의 말을 빌자면 브람스의 음악을 음반으로 듣는 것은 마릴린 먼로의 사진과 정사를 나누는 것과 같다. 코로나 동안 내가 들었던 아끼는 몇몇 음반 중 실체의 그림자라도 만들어낸 유일한 음반은 공연 실황을 녹음한 것으로, 전쟁 중의 푸르트벵글러, 마리스 얀손스와 오슬로 필하모니 관현악단, 클라우디오 아바도와 베를린 필하모니 관현악단의 음반이 가장 만족스러웠다. 스튜디오에서 녹음된 음반은 빈의 평론가 에두아르트 한슬리크가 브람스의 음악적 폭발성으로 분석한 “진실한 즐거움과 풍성한 연구의 끝없는 원천”을 전혀 만들어내지 못했다.

기본적으로 말러 애호가인 나로서는 브람스에 대한 이런 원초적인 욕구가 사뭇 놀라웠지만, 브람스 역시 우리를 놀라게 하는 것을 즐긴다. 한슬리크는 음악이 우리의 감정을 조종하며, 브람스의 영향력은 상상력과 환상에 있다고 주장했다. 브람스는 존재하는지도 몰랐던 곳으로 우리를 데려가는 작곡계의 탐험가 토머스 쿡(잉글랜드의 기업인. 세계 최초의 여행사 ‘토머스 쿡 앤 선’의 창업자_편집자 주)인 셈이다.

서로 다른 매력의 두 오케스트라

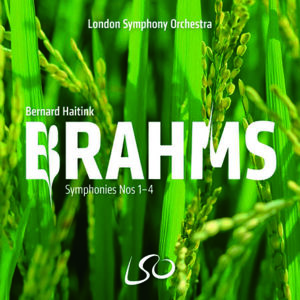

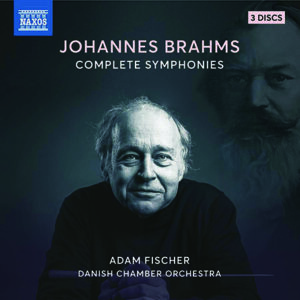

늦여름의 브람스 투어를 시작하며 나는 이틀 연속 두 장의 봉투를 개봉했다. 하나에는 대부분의 공연 실황을 실제로 봤던 베르나르트 하이팅크와 런던 심포니 오케스트라(이하 LSO)의 2003~2004년 바비칸 센터 공연이, 다른 하나에는 아담 피셰르와 덴마크 체임버 오케스트라의 작년 한 해 녹음이 담겨 있었다.

첫눈에 보기에 두 음반은 확연히 달랐다. 하이팅크는 파노라마식 전개를 보여주며 광범위한 음의 영역에 대형 오케스트라를 활용했고, 피셰르는 대담하고도 한 치의 실수도 없게 브람스를 모차르트식 관점으로 해부했다. 둘 사이를 번갈아 들으니 마치 최고의 식당 두 곳에서 하이팅크의 거대한 네덜란드 팬케이크와 피셰르의 부다페스트 향신료 요리를 대접받는 듯 했다.

모든 브람스 교향곡 사이클의 첫 시련은 베토벤 교향곡 9번 이후 반세기만에 세상에 나와 필연적으로 베토벤 교향곡 10번으로 환대 받은 작품인 교향곡 1번의 피날레에서 시작한다. 브람스는 20년에 걸쳐 자신의 첫 번째 교향곡을 작업했으며, 여섯 개의 도시에서 관객들의 박수와 갈채를 받기 전까지 이를 공개하지 않았다. 교향곡 1번은 바그너의 ‘니벨룽의 반지’가 초연된 1876년, 모두가 이기거나 지는 것으로만 평가하던 세계에 초연되었다. 바그너 애호가들은 이를 두고 퇴행적이며 심지어는 역행한다고 치부했다. 40대 초반의 브람스는 청자에게도 연주자에게도 쉬운 보상은 하지 않았으며, 오히려 우리를 더 깊이 파고들게 만들었다.

브람스 교향곡의 피날레는 바그너의 ‘니벨룽의 반지’ 중 ‘라인의 황금’ 속 굴곡만큼이나 완성하기가 까다롭다. 수많은 지휘자가 그 카타르시스를 느끼게 하는 거대한 선율에 도달하기 위해, 미국 독립기념일의 폭주족에 나타나는 지옥의 천사들(Hells Angels) 마냥 몰아 부친다. 최악으로는 카라얀, 솔티, 번스타인을 꼽을 수 있다. 진정한 브람스 애호가라면 음을 비옥한 토양에서 압박을 가하거나 화학 물질을 사용하지 않고 유기적으로 성장시켜야 한다. 그런 면에서 하이팅크는 유기 농법을 쓰는 정원사, 피셰르는 인테리어 디자이너라고 볼 수 있다. 두 사람은 조정된 느린 유보로 전체적인 만족을 이끌어낸다. 브람스 피날레에 있어 이들은 10점 만점에 10점이다.

오래, 그리고 깊이 브람스에 집중하라

두 음반이 다르기는 해도 나는 둘 모두를 거의 비슷하게 만끽했다. LSO의 전 프로듀서 제임스 맬린슨의 손길로 변화한 LSO는 내 기억보다 훨씬 매끄럽게 들리고, 피셰르의 연주자들은 채식주의자식 금욕에 가까운 덴마크식 음향으로 축적된 깊이만큼이나 웅장함을 자아낸다. 청취에 따라 내가 선호하는 부분은 다른데, 전원적인 교향곡 2번에서 피셰르의 군더더기 없음은 깊이를 드러내며, 3번에서는 하이팅크의 관대함이 압도적이다. 4번의 대부분에서는 코펜하겐식 미니멀리즘에 설득되고 말았지만, 피날레에서는 런던의 긍지가 승기를 잡는다.

스스로가 충분히 명확하지 않을까봐 나는 한 사람이 최상의 상태로 교향곡을 이해할 수 있는 양만큼만 집중하여 브람스에 절대적으로 몰입해 한 주를 보냈다. LSO 음반에는 보너스 트랙으로 ‘비극적 서곡’과 ‘이중 협주곡’(바이올린 고단 니콜리치·첼로 팀 휴_편집자 주)이 포함되었지만, 중요한 것은 교향곡이며 이 해석에는 지속적인 관련성을 통한 사람들의 동의가 있어야 할 것이다.

피셰르/덴마크 체임버 오케스트라

하이팅크/런던 심포니

왜 그래야 하는지를 설명하기란 쉽지 않다. 한슬리크 역시 나와 같은 문제를 겪었다. 교향곡 3번에 대해 그는 이렇게 썼다. “교향곡 3번은 평론가보다는 음악 애호가와 음악가를 위한 축제입니다. (…) 평론가의 화술은 작곡가의 재주에 반비례하여 감소합니다.” 브람스는 항상 처음 그 음악을 들을 때보다 점점 더 나아지고, 설명하기에는 매우 어렵다. 그는 대개 오랜 시간에 걸쳐 멀리 떨어져 있는 영혼의 일부를 건드리며, 그의 교향곡은 귓속에 들어오고 나서 1~2주가 지난 뒤에야 청자의 전두엽에 영향을 미친다. 브람스는 계속해서 주기만 하는 선물이나 다름없다.

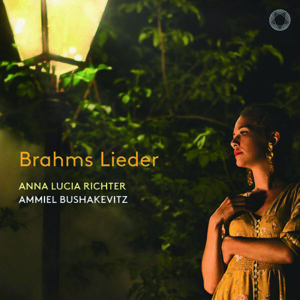

즉각적인 만족감이 필요한 이들에게는 거대한 야망도 가식도 없이 응접실에서의 티타임을 겨냥한 그의 가곡을 추천한다. 교향곡에서 벗어날 무렵, 독일인 소프라노 안나 루치아 리히터와 이스라엘인 피아니스트 아미엘 부샤케비츠의 브람스 가곡 음반이 도착했다. 리히터는 여느 젊은 성악가와는 다르게 날카로움 없이 강세를 두면서도 때론 우리 모두가 잠자리에서 들어본 적이 있는 자장가를 속삭인다. 가곡을 들을 때마다 나는 그 다양성에 놀라고 만다. 브람스는 들을 때마다 매번 새롭게 다가오는 음악을 해내며, 빛과 색을 품고 있는 그가 없다면 삶은 흑백에 가까울 것이다. 역병의 시대가 지나가는 와중에, 매일 아침 브람스의 축복에 감사하는 나날이다. 번역 evener

브람스 가곡

Pentatone PTC5186986

안나 루치아 리히터(메조소프라노)/

아미엘 부샤케비츠(피아노)

브람스 교향곡 전곡(1~4번)

LSO Live LSO0570 (4CD)

베르나르트 하이팅크/

런던 심포니 오케스트라

브람스 교향곡 전곡(1~4번)

Naxos 8574465-67 (3CD)

아담 피셰르/

덴마크 체임버 오케스트라

노먼 레브레히트 칼럼의 영어 원문을 함께 제공합니다

본 원고는 본지의 편집 방향과 일치하지 않을 수 있습니다

Through the two pandemic years, the composer I missed most was Johannes Brahms. Others I could listen to more or less contentedly on record, on radio and on-line, but Brahms resisted distanced attention. He is the most physical of composers – an imposing personality of rich, tangible textures that require bodily immersion in their musical totality. Put simply, you’ve got to be there. Brahms exists in the concert hall. To hear him on record is, to quote Otto Klemperer, like making love to a photograph of Marilyn Monroe. During Covid, I listened to certain cherished recordings, but the only ones that yielded a shadow of the real thing were those that had been taken live in concert – Furtwängler in mid-War, Mariss Jansons in Oslo and Claudio Abbado in Berlin among the most satisfying. A studio production yields nothing of that ‘inexhaustible fountain of sincere pleasure and fruitful study’ that the Viennese critic Eduard Hanslick diagnosed as the musical payload of Brahms. Given that I am primarily a Mahlerian, this primal need for Brahms surprised me, but then Brahms likes to surprise us. Hanslick argued that while music may manipulate our emotions, Brahms’s impact is on the imagination and the fantasy. He is the Thomas Cook of composers, taking us places we never knew existed. Setting off on a late-summer’s Brahms tour, I broke open two envelopes on successive days. One contained Bernard Haitink’s 2003-4 Barbican concerts with the London Symphony Orchestra, most of which I attended. The other brought Adam Fischer with the Danish Chamber Orchestra, recorded over the past year. On first impression they are markedly different. Haitink goes for panoramic sweep, deploying a large orchestra across a broad sonic front. Fischer strips Brahms daringly down to Mozartian dimensions, no margin for error. Switching from one set to the other delivers the best of two restaurants – Haitink’s big Dutch pancake, Fischer’s Budapest spice. The test of any Brahms symphonic cycle begins in the finale of the first symphony, a work that was inevitably hailed as Beethoven’s tenth, coming as it did half a century after the ninth. Brahms spent 20 years on his first symphony and did not allow it to be published until audiences in six cities rose in acclaim. The first symphony was premiered in 1876, the year of Wagner’s Ring, all to play for and a world to win or lose. Wagnerians dismissed it as regressive, even reactionary. Brahms, in his early 40s, did not yield cheap rewards whether for listeners or performers. Brahms makes us dig deep. The finale is as tricky to negotiate as any bend in Wagner’s Rhine. Many conductors rev up the approach to its cathartic big tune, vroom-vroom, like Hells Angels on the Fourth of July; Karajan, Solti and Bernstein are among the worst offenders. A true Brahmsian allows the tune to grow organically from the surrounding soil, nothing forced or chemically induced. Haitink is an organic gardener, Fischer an interior designer. Each produces a calibrated slow deferral of holistic satisfaction, the perfect ten of Brahms finales. Different as they are, I enjoyed the two sets almost equally. The LSO, tweaked by the late master-producer James Mallinson, sound sleeker than I remembered and if the Danish acoustic verges on vegan self-denial, the players achieve grandeur by cumulative degree. My preference varies from one listening to the next. Fischer’s lack of ornament brings out more depth in the bucolic second symphony, while Haitink’s largesse is overwhelming in the third. I was persuaded by Copenhagen minimalism in most of the fourth symphony, although London pride shades it in the finale. In case I haven’t been specific enough, I have had an absolute blast of an immersive week in top-drawer Brahms, as concentrated a dose as one can get of symphonic music at its best. The LSO set contains bonus tracks of the double concerto, the tragic overture and the second serenade, but the symphonies are the thing and these accounts will restore anyone’s faith in their enduring relevance. Why that should be so is not easy to describe. Hanslick had the same problem as I do. The third symphony, he wrote, ‘is a feast for the music lover and musician rather than for the critic, (whose)… eloquence declines in inverse proportion to that of the composer.’ Brahms is always greater than he sounds on first hearing and much harder to describe. He reaches remoter parts of the psyche, often with a considerable time delay so that a symphony may only impact on the listener’s frontal lobes a week or two after it has entered the ears. Brahms is the gift that just keeps on giving. For those who require instant gratification, I would recommend his songs for voice and piano which, aimed at the tea-time drawingroom, have neither high ambition nor pretension. As I emerged from the symphonies, there arrived a Pentatone recital of Brahms Lieder by the German soprano Anna Lucia Richter with the Israeli pianist Ammiel Bushakevitz. Richter, unlike many young voices, achieves emphasis without shrillness, practically whispering the lullabies that all of us have heard at bedtime. Each time I listen to the Lieder I am amazed at their versatility. Brahms contrives to be new each time we hear him, a bearer of colour and light without whom life would be monochrome. As the plague years recede, I give thanks each morning for the blessings of Brahms.

글 노먼 레브레히트 영국의 음악·문화 평론가이자 소설가. ‘텔레그래프’지, ‘스탠더즈’지 등 여러 매체에 기고해왔으며, 지금 이 순간에도 자신의 블로그(www.slippedisc.com)를 통해 음악계 뉴스를 발 빠르게 전한다