리하르트 슈트라우스

그보다 더 재미없는 작곡가가 있었던가?

And so to Richard Strauss:

was there ever a less interesting composer?

탄생 150주년을 맞이한 슈트라우스. 그에게 감정적 또는 지적 깊이가 있었다면, 그것은 깊숙한 어디엔가 숨겨져 있을 것이다

음악적 부분을 제외하면 그는 뭐든지 자기 내키는 대로 하는 촌뜨기였으며, 일생은 단조로움의 연속이었다. 어떻게 ‘살로메’와 ‘4개의 마지막 노래’ 같은 세계적인 작품이 그렇게 따분한 사람에게서 탄생했는지 실로 불가해한 창조의 미스터리다.

우리는 모든 위대한 작곡가들이 단조로운 일상보다 뭔가 대단하고 다채로운, 그들의 작품만큼이나 위대한 삶을 살 것이라고 기대하는 경향이 있다. 그런 생각의 일례로, 최근 크게 호평 받고 있는 바흐의 전기에서 저자 존 엘리엇 가드너는 요한 제바스티안 바흐에게 이른바 ‘분노조절 결함’이 있었던 것으로 보고 있다. 이해 불가능한 이상을 칭송하는 한편 그를 인간화하기 위한 인지편향적인 평가인 셈이다.

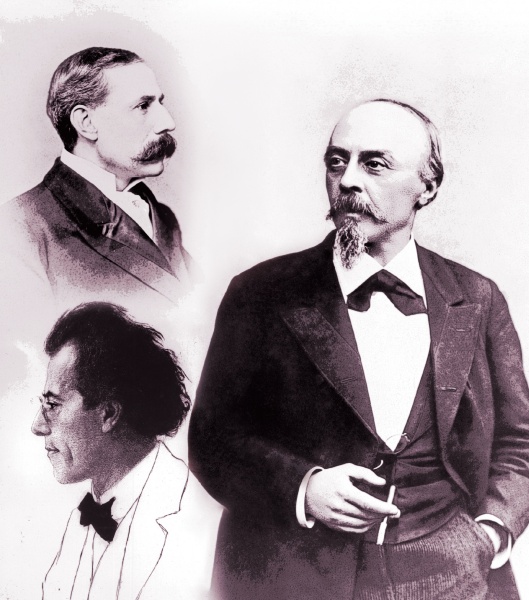

리하르트 슈트라우스는 바흐처럼 감정이 격한 사람이 아니었다. 1864년부터 1949년까지 그의 긴 일생 어디에도 열정의 불꽃이라든지, 바이에른 사람 특유의 무신경함에 감정의 소용돌이가 일었던 상황을 전혀 찾아볼 수 없다. 뮌헨 오케스트라의 호른 연주자이자 양조장 상속인의 아들로 태어난 리하르트는 (그의 아버지는 자신이 발할라-북유럽 신화에 묘사된 이상향-와 혼인했다고 생각했던 것 같다) 어린 시절 제대로 된 음악교육을 받은 적이 한 번도 없었다. 그가 어린 나이에 벌써 성숙미와 세련미를 갖추고 인상적인 주제와 서술적 요지까지 담은 곡들을 쓸 수 있었던 것은 오롯이 가족으로부터 물려받은 음악성에 의존해서였다. 그는 청중이 어디까지 수용할 수 있는지 그 한계를 알고 있었다.

‘돈 후안’의 바이마르 초연 당시 그의 나이는 불과 24세였다. ‘돈 후안’은 당시 한창 유행이던 교향시 시리즈의 첫 작품이었다. 슈트라우스의 교향시들은 ‘죽음과 변용’ ‘틸 오일렌슈피겔의 유쾌한 장난’ ‘차라투스트라는 이렇게 말했다’ ‘돈키호테’ ‘영웅의 생애’ 등 작품명이 마치 그림 제목처럼 생생하다. 그 당시 슈트라우스는 여성에 대한 환상과 독일의 맥줏집, 신령스러움, 그리고 니체의 철학을 작품에 담아내고자 했다. 그는 언제나 절충적이고 시장을 지향하는 작곡가였다.

바이마르의 지휘자로 있을 당시 그는 훔퍼딩크의 바그너풍 오페라인, 두려움에 떠는 아이들을 위한 ‘헨젤과 그레텔’ 초연을 지휘했다. 30세에는 장군의 딸이자 소프라노 가수인 파울리네와 결혼했고, 35세에는 베를린 슈타츠오퍼의 음악감독이 되어 빈의 구스타프 말러와 함께 독일 오페라 무대를 휩쓸었다.

감정 기복이 심한 말러가 슈트라우스에 대해 “각자 산의 반대쪽에서 굴을 뚫고 들어와 중간에서 만날 수밖에 없는 광부” 같은 동반자 관계라고 생각한 반면, 슈트라우스는 말러의 진보적 이상과 동의하는 부분이 거의 없었다. 말러는 무대 위에 외설스러운 ‘살로메’를 올리기 위해 자신의 직업을 걸고 애썼지만, 슈트라우스는 안전한 쪽을 택했다. 말러는 오페라 연주를 끝내고 나면 두통과 탈진 상태에 이르렀지만, 슈트라우스는 연주에 땀을 빼는 지휘자는 아마추어나 다를 바 없다고 말했다. 말러는 예술에서 구원을 보았으나, 슈트라우스는 이렇게 말했다. “내가 무엇으로부터 구원을 받아야 하는 건지 모르겠다. 아침에 책상에 앉아 아이디어가 떠오르면 구원이란 건 필요 없다. 말러가 말하는 구원이란 대체 무슨 뜻인가?”

슈트라우스는 규칙적인 습관의 소유자였고 터프한 부인의 보호를 받았으며, 그의 꿈은 사회적 ·금전적 성공이었다. ‘살로메’가 알몸을 노출한 댄스와 이단적인 스토리로 물의를 빚은 상황을 두고 그는 태연히 말했다.

“물의를 일으킨 덕분에 가르미슈(바이에른 주 남부에 위치한 풍광 좋은 도시)에 집을 짓지 않았나.”

슈트라우스가 악평 세례를 받은 오페라에는 마치 고무줄이 끊어지기 직전까지 조성을 늘려 만들어낸 절정의 불협 F화음도 들어가 있다. 잠시 동안 아방가르드를 이끌었던 그는 1909년 ‘엘렉트라’에서도 절정의 불협화음을 사용한다. ‘엘렉트라’는 시인 휴고 폰 호프만슈탈과 함께 만든 다섯 개의 작품 중 첫 작품이다. 이후 작곡한 ‘장미의 기사’에서는 불협화음을 크게 순화시켜 깊은 편안함을 주는 풍성한 화음들로 채웠고, 이전의 두 오페라에서 보인 위험하고 괴상한 모습 역시 은근한 성적 암시들로 대체했다.

이후 슈트라우스는 논란을 일으키지 않았다. 부르주아 계층의 관용을 시험해봐야 흥행에 도움이 되지 않는다고 판단한 것이다. 제1차 세계대전에도 그의 명성이나 부는 타격을 입지 않았고, 5년간 빈 슈타츠오퍼의 수장으로 일하며 그의 명성은 더욱 견고해졌다.

그 어느 때보다 왕성한 활동을 하던 슈트라우스는 나치 정권이 들어서면서 음악계의 장로가 되었다. 독일제국음악원의 수장을 맡은 것이다. 그의 이런 결정은 인종적·정치적 이유를 바탕으로 그 자리가 음악가의 직업을 유지하기에 가장 적절하다는 판단 때문이었다. 그의 무표정한 얼굴에는 그 어떤 도덕적 거리낌도 보이지 않았고, 1936년 히틀러 정권 당시 올림픽 찬가를 쓰기도 했다.

그의 평탄하던 삶에 문제가 생긴 것은 자신의 마지막 대본작가이자 추방당한 유태인 슈테판 츠바이크에게 쓴 편지를 중간에 도둑맞으면서부터였다. 거기다 자신의 유태인 며느리와 손주들도 가우라이터(나치당 지방장관)의 명령 하나면 목숨을 잃을 수도 있다는 사실 역시 깨닫기 시작했다. 슈트라우스는 제2차 세계대전 동안 엄청난 불안감 속에 살았고, 악명 높은 발두어 폰 시라흐(나치 청년단의 지도자)의 보호를 받으며 지내는 동안 말러와 한때 공감했던 후기 낭만파 음악으로 돌아갔다.

1948년, 그는 본의 아니게 지내게 된 유럽의 가장 호화로운 호텔 몽트뢰 팰리스에서 ‘4개의 마지막 노래’를 작곡한다. 이 작품은 인생의 불쾌한 순간들로부터 자신을 지켜준 아내 파울리네에게 바치는 찬란한 감사의 표현이자 고별사였다. 그는 임종을 앞두고 죽음을 가리켜 자신이 ‘죽음과 변용’에 묘사한 그대로라고 표현했다. 슈트라우스는 자신의 것을 표현하는 데는 열심인 반면 남의 것을 잘 배우지는 않는 사람이었다. 그에 대한 여러 편의 전기가 쓰인 오늘날, 그에게 감정적 또는 지적 깊이가 있었다면, 그것은 깊숙한 어디엔가 숨겨져 있을 것이다.

슈트라우스와 가장 비슷한 음악적 동반자는 말러가 아니라 에드워드 엘가였다. 엘가 역시 악기로 가득한 집에서 자랐고, 사회적 명예와 평범한 즐거움을 갈망했다. 경마장에서의 하루가 그 어느 때보다 행복하고, 밥 한 끼를 빼앗기면 그보다 우울한 일이 없는 사람이었다. 이 두 작곡가는 직감적이고 자연적으로 서로의 존재와 음악에 감사했다. 서로의 교향시를 지휘하기도 했으며, 창조와 삶에 관한 한 서로의 냉정하고 차분한 접근법을 좋아했다. 그들은 각자 기존의 서양 음악이 가진 한계에 도전하려는 의도 없이 음악의 규범에 영원히 남을 기여를 했다.

이 얘기가 별로 재미없다면, 달리 할 말이 없다. 슈트라우스의 평범함에서 아무도 따라 할 수 없는 웅장한 절정의 순간들이 탄생했다. ‘장미의 기사’ 마지막 트리오는 아마도 ‘코시 판 투테’ 이후 가장 완벽한 곡일 것이다. ‘엘렉트라’의 ‘팔레스타인의 밤’은 독일 작곡가에게서 나오리라고는 상상할 수도 없던 스타일의 곡이다. 그의 후기작 오보에 협주곡과 ‘4개의 마지막 노래’는 인간이 자신을 아는 것 이상으로 인간에 대해 잘 말해주고 있다. 이래도 흥미가 없다면, 그럼 흥미 없는 걸로. 올해로 탄생 150돌을 맞는 슈트라우스는 오늘날도 자신의 음악 속에서 건재하다.

번역 윤수린

And so to Richard Strauss:

was there ever a less interesting composer?

노먼 레브레히트 칼럼의 영어 원문을 함께 제공합니다

Music aside, the man was a self-indulgent boor, his life a string of platitudes. How the universal sound worlds of Salome and the Four Last Songs can have arisen from so dreary a human source is an unfathomable mystery of creation.

Unless, that is, we require all authors of great work to manifest an equivalent greatness, to be in some way larger and more colourful than their humdrum lives — the mindset that, in a highly acclaimed recent biography, prompts John Eliot Gardiner to ascribe failings of ‘what we would call anger management’ to Johann Sebastian Bach, a bias of blame that aims both to elevate and to humanise an incomprehensible ideal.

Richard Strauss was no raging Bach. Search his long life end to end, 1864 to 1949, and you will find no flare of passion, no situation in which he ever lost urbane control of his stolid Bavarian manners. The son of a Munich orchestral horn player and a brewery heiress (his father, who played in Wagner premieres, must have thought he’d wedded Valhalla), the young Richard never had a formal music lesson, relying on a familiarity with the family craft to compose pieces of precocious sheen, catchy themes and narrative thrust. He knew the limits of what an audience would bear.

He was 24 when Don Juan was performed at Weimar, the first in a series of fashionable tone poems with graphic titles — Death and Transfiguration, Till Eulenspiegel’s Jolly Pranks, Thus Spake Zarathustra, Don Quixote, A Hero’s Life. Strauss at this stage aimed for feminine fantasies, the beer garden, the numinous and the Nietzschean. He was nothing if not eclectic, always market oriented.

As conductor in Weimar, he led the first production of Humperdinck’s Hansel and Gretel, a Wagnerian opera for terrorised children. At 30 he married Pauline, a general’s soprano daughter and at 35 he became chief conductor at the court opera in Berlin, sharing with Gustav Mahler in Vienna a dominance of the German-speaking opera stage.

But where the excitable Mahler imagined that he and Strauss were allies, ‘like two miners tunnelling a mountain from opposite sides, destined to meet in the middle’, Strauss shared few of his friend’s progressive ideals. Where Mahler put his job on the line in a bid to stage salacious Salome, Strauss played safe with his programming. Where Mahler ended an opera in migraine-stricken exhaustion, Strauss declared that a conductor who broke sweat was no better than an amateur. Where Mahler saw redemption in art, Strauss said: ‘I don’t know what I am supposed to be redeemed from. When I sit at my desk in the morning and an idea comes into my head, I surely don’t need redemption. What did Mahler mean?’

A man of regular habits, guarded by a dragon wife, Strauss’s ambitions were social and pecuniary. Of the striptease dance in Salome, scandalous as much for its heresy as its nudity, he would say, blithely, ‘the damage built me a house in Garmisch.’ Behind the opera’s notoriety, he stretched tonality almost to snapping point in a climactic, clashing F chord. For a brief moment, he led the avant-garde. In 1909, he toyed again with dissonance in Elektra, the first of five joint ventures with the poet Hugo von Hofmannsthal, only to retreat in Der Rosenkavalier to the deep, deep comfort of lush harmonies, replacing the dangerous pathologies of his two previous operas with a nudge-wink sexual suggestiveness.

Strauss never again frightened the horses. He had tested bourgeois tolerance and decided it was bad for business. The First World War left him unharmed in fame or fortune. A five-year spell at the head of the Vienna Opera cemented his esteem.

Ever productive, he was entering his Grand Old Man phase when the Nazis came to power in Germany. Strauss agreed to become head of the Reichsmusikkammer, the body that decided who was fit, on racial and political grounds, to be a professional musician. No moral qualm troubled Strauss’s impassive countenance. He wrote an Olympic hymn for Hitler’s 1936 Games.

What got him into trouble was an intercepted letter of mild dissent to his latest librettist, the exiled Stefan Zweig, along with a dawning realisation that his daughter-in-law and grandsons, being Jewish, could be snuffed out on the order of a Gauleiter. Strauss lived out the Second World War in a state of mounting anxiety, protected by the odious Baldur von Schirach, returning in his music to the late-romantic language he had once shared with Mahler.

The Four Last Songs – written in 1948 during involuntary displacement in Europe’s most luxurious hotel, the Montreux Palace – amount to an effulgent thanksgiving to Pauline for protecting him from most of life’s unpleasantness. The texts he chose are valedictions. Death, he would say on his deathbed, ‘is just as I composed it in Death and Transfiguration’. Strauss was a man who gave much and learned little. If he had emotional or intellectual depths they remain, after many biographies, well hidden.

His closest parallel in music is not Mahler but Edward Elgar who, like Strauss, grew up in a provincial home full of musical instruments, who craved imperial honours and conventional pleasures, never happier than on a day at the races, never gloomier than when deprived of a meal. The two composers enjoyed a mutual appreciation, intuitive and unforced. Each conducted the other’s tone poems, each appreciated the other’s phlegmatic approach to creation and life. Each made a lasting contribution to the canon of western music without wishing to challenge its parameters. Each worked well within his means.

If this sounds uninteresting, so be it. From Strauss’s conventionality came moments of inimitable sublimity. The closing trio of Der Rosenkavalier may be the most perfect piece of vocal writing since Cosi fan tutte. The Palestinian night in Elektra is like nothing imagined before by a German composer. The late oboe concerto and the four last songs know more of humanity than humanity perhaps knows of itself. If that’s uninteresting, I’ll take uninteresting. Strauss is 150 years old, still going strong. NL