노먼 레브레히트 칼럼

위대한 작곡가 콧대 꺾기

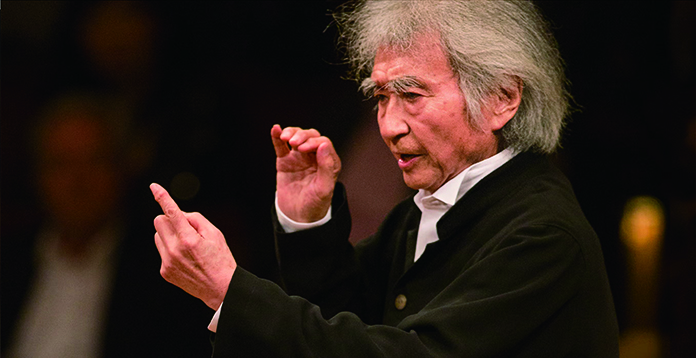

서거 50주기 맞은 스트라빈스키1882~1971는 과연 ‘위대한 작곡가’일까?

50년 전인 1971년 4월, 이고르 스트라빈스키가 생을 마감하고 난 뒤 문화계 전반에 거대한 그림자가 드리우기 시작했다. 그의 출판 담당자는 음악이 미켈란젤로 이후의 예술과 같아질 것이라 말했다.

이제 보니 그 담당자의 말이 정말 맞았다. 지난 반세기 동안 스트라빈스키만큼 명성과 위상을 얻었던 작곡가는 단 한 명도 없었으며, 엘리제궁이나 백악관으로부터 저녁 식사를 초대받았던 작곡가 또한 존재하지 않았다. 스트라빈스키는 최후의 위대한 작곡가였으며, 그의 죽음 이후로 그 반열(班列)로 향하는 문은 닫혔고 열쇠는 사라져버렸다.

누가 이의를 제기하기 전에, 우선 이런 흐름이 종지부를 찍었다는데 환호를 보낸다. BBC에서 보스턴 심포니에 이르기까지 현재 전 세계는 고인이 된 백인 남성 작곡가들을 지금까지 잘 알려지지 않았던 다양한 인종의 작곡가들로 대체하는 중이다. 위대한 작곡가를 추종함에 있어 존재하던 케케묵은 숭배에 관해서는 집단적 죄책감과 고해의 물결이 일고 있다.

올여름 음악 축제에서 스트라빈스키 역시 그의 특권을 점검 당하게 될 예정인데, 이 역시 늦은 감이 있다. 물론 아직도 언론사의 비평가들이 그를 두고 ‘당대 최고’라고 찬양하는 모습을 볼 수 있지만 말이다.

다시 보는 스트라빈스키

이제는 위대한 스트라빈스키의 콧대를 꺾어야 할 시간이다. 그의 명성에는 행운도 한몫했다. 상트페테르부르크에서 림스키 코르사코프(1844~1908)에게 작곡을 배우던 스트라빈스키는 세르게이 디아길레프(1872~1929)의 발레 르네상스 프로젝트에 발탁됐다.

스트라빈스키가 파리에서 처음으로 선보인 발레 음악 ‘불새’와 ‘페트루슈카’는 놀라울 정도로 명성을 얻었고, ‘봄의 제전’의 인기 역시 악명이 높았다. 남은 평생 그가 외식할 때면, 1913년 5월(‘봄의 제전’이 초연된 시기)과 같은 폭동이 곁들여질 정도였다. 만약 스트라빈스키가 그 이후로 더는 작곡하지 않았다면, 오늘날 그의 인기가 이 정도는 아니었을 것이다.

스트라빈스키는 ‘페트루슈카’의 리드미컬한 추진력을 가져와 우레와 같은 소음을 ‘제전’의 원동력으로 이용했다. 뒤따른 소동은 스트라빈스키를 성난 젊은 모더니즘 음악가이자 음악계의 피카소로 공고히 자리매김해 주었다. 전쟁이 발발하기 전까지 장 콕토와 칵테일을, 아폴리네르와 경구를 나누던 그는 이내 자신의 영감 상자에 남은 것이 별로 없다는 사실을 깨닫는다.

러시아 땅을 벗어나자 그의 영감은 메말라갔고, 1923년 초연된 발레 ‘결혼’은 관객몰이용 민속 문화로 되돌아간 정도였다. 공산주의 체제가 그의 망명 생활을 지속시키자 스트라빈스키는 기본적으로 모차르트 또는 로시니의 틀에 레몬과 라임만 더한 ‘신고전주의’ 스타일을 발명해낸다.

그의 중년은 모방의 연속이었다. 1930년 ‘시편 교향곡’마저 없었더라면 혹자는 슬럼프라고 치부할 수 있었을 것이다. 발레 공연 한 편, 아니 세 편은 그의 유명세를 유지해 주었고 ‘패션왕’ 코코 샤넬과의 스캔들은 당사자들에게 해를 끼치기는커녕 그와 샤넬의 홍보에 한몫했다. 당대 모든 사람은 스트라빈스키의 이름을 한 번쯤 들어봤을 정도였다.

미국으로 건너간 스트라빈스키는 우디 헤르만(1913~1987)을 위한 클라리넷 협주곡과 관현악계의 백만장자들을 위한 그다지 위엄 없는 교향곡 두 곡을 작곡한다. 1951년 그의 선정적인 오페라 ‘난봉꾼의 행각’은 별다른 노력 없이도 전 세계 헤드라인을 장식했다.

생전 스트라빈스키와의 인연으로 그의 전기(1972)를 쓴 미국 지휘자 로버트 크래프트(1923~2015)의 말에 따르면, 스트라빈스키는 당시 막 세상을 떠난 아르놀트 쇤베르크(1874~1951)가 창안한 음렬주의 무조음악으로 전향함으로써 전환기를 맞았다. ‘진보’에 대한 계산적인 신뢰를 발판삼아 도약한 그는 포스트모더니즘의 지도자이자, 피에르 불레즈나 칼 하인츠 슈톡하우젠식 허무주의의 수호성인, 음악계의 명망 높은 최고 권위자로 대우받게 된다.

1960년대부터 음악계의 대부 스트라빈스키의 인정 없이는 그 어떤 작곡가도 성공 가도에 진입할 수 없었으며, 지금까지도 비평가들은 그의 명성에 감히 바늘 하나 꽂기 어려워한다. 사실 그 명성을 터뜨리는 것은 그리 어려운 일이 아닌데 말이다.

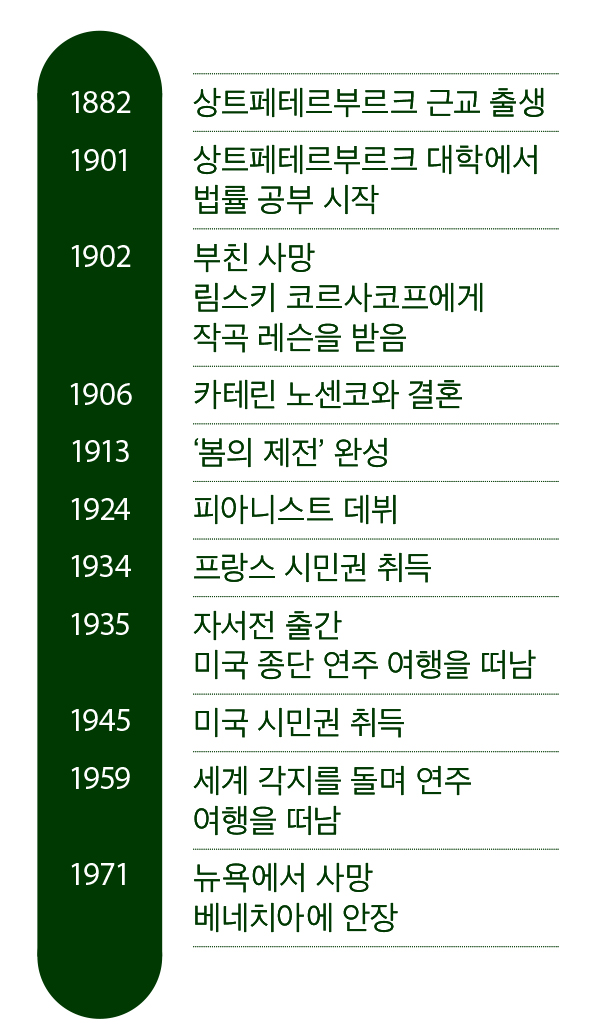

스트라빈스키의 일생

이고르 스트라빈스키와 세르게이 디아길레프

ⓒRue des Archives

대열에 들지 못한 이

논의를 위해 스트라빈스키보다 아홉 살 어리고 스트라빈스키와 똑같이 디아길레프의 프로젝트를 거친 세르게이 프로코피예프(1891~1953)를 비교 선상에 세워보자. 통통 튀는 피아노 협주곡, ‘스키타이 모음곡’ Op.20과 함께 등장한 프로코피예프는 1918년 초연한 교향곡 1번에서 더욱 성숙한 모습을 보여주었다. 볼셰비키 혁명으로 망명한 그는 시카고에서 초연된 ‘세 개의 오렌지 사랑’, 세르게이 쿠세비츠키를 위한 교향곡 몇 곡과 더불어, 무대에는 적합하지 않은 선정적인 수녀들에 관한 1927년 오페라 ‘불의 천사’를 작곡한다.

미국 대공황과 유럽의 정치적 침체기로 인해 1936년 그는 러시아로 돌아가겠다는 조마조마한 결심을 한다. 이러한 결심으로 인해 그의 첫 번째 아내는 시베리아에서 긴 형을 살게 되었고 또 다른 불편한 상황이 뒤따랐지만 참혹한 환경 속에서도 프로코피예프의 음악에 대한 열정은 마르지 않았다.

모스크바 중앙 어린이 극장의 ‘피터와 늑대’부터 볼쇼이 극장의 ‘전쟁과 평화’에 이르기까지 그의 책상을 거쳐 간 모든 곡은 완벽하게 빛났다. 곡의 요소는 당대의 교리에 조금도 영향받지 않은 듯 매우 ‘프로코피예프’적이었다. 그의 교향곡 5번은 제2차 세계대전의 결정적인 작품 중 하나이며, 프로코피예프가 스비아토슬라프 리히테르와 에밀 길렐스를 위해 작곡한 세 편의 소나타는 그야말로 피아노 연주곡의 정점이다.

스탈린 정부는 그를 위협과 궁핍으로 굴복시켰지만, 1953년 3월 5일 독재자 스탈린과 같은 날 사망한 프로코피예프에 러시아인들은 눈물을 감추지 못했다. 그의 음악은 유행에서 뒤떨어진 적이 한 번도 없었으며 불레즈식의 지지 또한 필요로 하지 않았다. 교향곡 7곡, 피아노 협주곡 5곡, 스탈린상 수상 6회, ‘폭군 이반’ 등 그의 업적은 어마어마하다.

프로코피예프는 예술 그 자체를 위해 예술 작품을 썼다. 바이올린 협주곡, ‘신데렐라’ ‘로미오와 줄리엣’ 등 열 편이 넘는 그의 작품들은 우리 일상 속에 자리 잡아 모든 세대를 아우르며 각별한 의미를 갖게 되었고 축구 경기장이나 헬스클럽에서 울려 퍼졌다.

위대한 작곡가란

모차르트 같이 축복받은 선율을 타고난 프로코피예프는 당대의 평범한 시민이었다. 아무도 그를 ‘위대한 작곡가’라고 임명하지 않았다. 이는 프로코피예프가 자기 홍보를 할 필요가 없었기 때문이기도 했지만, 다른 한편으로는 위대한 작곡가란 음악에 있어서 좋은 것이 무엇인지, 정치인과 대중은 무엇을 위해 돈을 지불할지를 가장 잘 안다고 말하는 음악 산업의 구성원이기 때문이다. 프로코피예프는 결코 백악관에 보낼 만한 인물이 아니었고, 또한 그는 셔츠에 튀지 않게끔 생선을 발라 먹지도 못했다. 반면에 스트라빈스키는 엘리제궁 해산물 요리에 나오는 모든 수저 종류를 꿰고 있었다.

스트라빈스키의 악보를 살펴보면 여러 가지 색깔로 모든 음을 정확하고 깔끔하게 표시해둔 것을 확인할 수 있다. 프로코피예프의 악보에서 화음들은 여기저기에 흩어진 채 페이지를 떠나 청중의 귓속으로 향하고 싶어 안달이 나 있다.

위대한 작곡가답게 스트라빈스키의 음악은 잘 낡지 않는다. 그의 음악은 대부분 먼 거리에 있고, 포착하기 어려우며, 계략적이고 이지적이고, 또 냉담하다. 또한 대부분은 대개 연주되지도 않는다. 올해의 출사표는 아마도 스트라빈스키의 마지막 행보가 될 것이다.

글 노먼 레브레히트

영국의 음악·문화 평론가이자 소설가. ‘텔레그래프’지, ‘스탠더즈’지 등 여러 매체에 기고해왔으며, 지금 이 순간에도 자신의 블로그(www.slippedisc.com)를 통해 음악계 뉴스를 발 빠르게 전한다

(노먼 레브레히트 칼럼의 영어 원문을 함께 제공합니다)

Taking down Great Igor

Igor Stravinsky cast such a huge shadow over the cultural estate that when he died, fifty years ago this month, his publisher said that music would be as art was after Michelangelo. We can now confirm that he was right. In half a century, no composer has attained the fame and stature of Stravinsky, none has dined with ease at the Elysée and the White House. Stravinsky was the last of the Great Composers. Once he was gone, they locked the canon and threw away the key.

Before you contest that proposition, let’s raise a cheer for the closure of the canon. Across the world right now, from the BBC to the Boston Symphony, dead white male composers are being replaced with diverse unknowns amid a confessional wave of collective guilt at our colonial worship of the Great Composers cult. Stravinsky will have his privilege checked at this summer’s music festivals, and about time, too. But I still see newspaper critics saluting him as the ‘greatest’ of his century.

It’s about time we took down Great Igor, at least a peg or two. Luck played a part in his ascendance. As a Rimsky-Korsakov student in St Petersburg he was recruited by Serge Diaghilev to his ballet renaissance project. Stravinsky’s first two Paris ballets – Firebird and Petrushka – were spectacularly popular. His third, The Rite of Spring, was spectacularly notorious. Stravinsky dined out on the May 1913 riots for the rest of his life. Had he written nothing more, he would be no less famous today.

Drawing on the rhythmic propulsion of Petrushka, he employed thunderous noise as the driving force of the Rite. The ensuing ructions established Igor as the angry young musician of modernism, the Picasso of percussion. He mixed cocktails with Cocteau and aphorisms with Apollinaire until war broke out, when he found there was not much left in his toolkit.

Removal from Russia dried up his sources, throwing him back on touristy folklore in Les Noces. When Communism perpetuated his exile, he invented a ‘neo-classical’ style, which was essentially pseudo-Mozart or Rossini with a twist of lemon and lime. His middle period was mostly pastiches. Were it not for the 1930 Symphony of Psalms, one could write it off as a slump. A ballet or three kept him in the spotlight and an affaire with the fashion queen Coco Chanel did his PR, and hers, no harm at all. Everybody had heard of Stravinsky Removing himself to America, he wrote a jazz clarinet concerto for Woody Herman and two unimposing symphonies for orchestral millionaires. In 1951 his libidinous opera, The Rake’s Progress made all the right world headlines without changing the weather.

The game-changer for Stravinsky was his conversion – through the aptly named Robert Craft – to the serial atonality of the lately-deceased Arnold Schoenberg. This leap of calculating faith in ‘progress’ enshrined Stravinsky as the Moses of post-modernism, patron saint to the nihilism of Pierre Boulez and Karlheinz Stockhausen, and supreme arbiter of musical reputation. No composer could make a career from the 1960s on without a nod to godfather Stravinsky. No critic has, up to now, dared to take a pin to his balloon, and it’s really not that hard to burst.

Let’s subject him to comparison, for argument’s sake, with Serge Prokofiev, a Russian nine years his junior who rose by the same route, through the Diaghilev talent machine. Prokofiev announced his arrival with a ballistic piano concerto and Scythian Suite, mellowing into a 1918 Classical Symphony. In Bolshevik exile, he wrote The Love of Three Oranges for Chicago, a couple of symphonies for Serge Koussevitsky and an unstageable 1927 opera about libidinous nuns, The Fiery Angel.

America’s Depression and Europe’s political gloom led to a nail-bitten decision return to Russia in 1936. The move cost his first wife a long sentence in Siberia, among other inconveniences, but Prokofiev never ran dry of music no matter how harrowing his circumstances.

From Peter and the Wolf for a Moscow children’s theatre to War and Peace for the Bolshoi, every score that left his desk was polished to perfection and each was Prokofiev in every line, paying no dues to current doctrines. His fifth symphony is one of the defining works of the Second World War and the three sonatas he wrote for Richter and Gilels are summits of piano repertoire.

Stalin brought him to his knees with threats and deprivations and his death in March 1953 on the same day as the dictator in March 1953 brought Russians out in tears. His music has never gone out of fashion or needed Boulezian advocacy. The legacy is immense – 7 symphonies, 5 piano concertos, 6 Stalin Prizes and a score for Ivan the Terrible. He wrote works of art, for art’s sake. At least a dozen scores – the violin concertos, the Cinderella ballet, Romeo and Juliet – are part of our common culture, meaningful to people of all ages, boomed out in football stadia and fitness gyms.

Blessed with Mozartian gift for melody, Prokofiev was a citizen of his century. Nobody ever nominated him as its ‘greatest composer’ – in part, because he did not need brand inflation and, in equal part, because the Great Composer is a construct of a music establishment that claims to know best what is good for music, what politicians and the public will pay for. Prokofiev was never a man they could send to the White House. He could not eat fish without spattering his shirt. Stravinsky, on the other hand, could name every instrument of cutlery on the Elysée seafood tray.

Examine Stravinsky’s manuscripts and you’ll see neatness in several colours, each note minutely in its place. With Prokofiev, chords wobble all over the staves, bursting to get off the page and into our ears. Great Composer that he is, Stravinsky’s music has not worn well. Much of it is aloof, elusive, strategic, cerebral and cold. Most is generally unplayed. This year’s roll-out might well be his last.