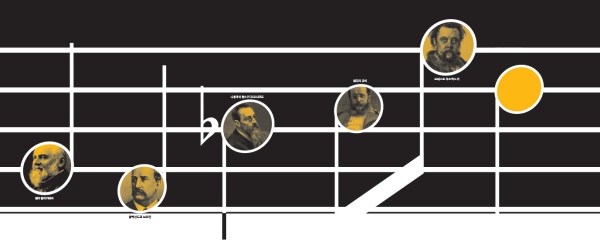

러시아의 강력한 소수 ‘쿠치카’

음악적 무기력 상태에 빠져있던 조국을 구해낸 러시아 5인조.

그들의 만남은 우연을 가장한 필연이었다

1803년 아일랜드에서 상트페테르부르크로 이주한 존 필드부터 오늘날 소의 말하는 ‘러시아 음악’은 시작된다. 그의 제자였던 주인집 아들 미하일 글린카는 러시아의 기나긴 겨울을 나기 위해 응접실에 모여 앉아 한담을 나누거나 오락거리를 즐기는 것을 질색하는 사람이었다. 글린카는 1830년대에 서사적 오페라인 ‘황제에게 바친 목숨’ ‘루슬란과 루드밀라’를 썼으나 흥행에 실패하자 작곡을 그만두고 만다.

음악적 무기력 상태의 러시아를 깨우는 건 한 명의 힘으로는 역부족이었다. 변화를 일으킨 주인공은 러시아 5인조 또는 쿠치카(Могучая ‘Кучка’, 강력한 소수)라 불리는 다섯 명의 작곡가들이었다. 스티븐 월시는 그의 새로운 저서 ‘무소륵스키와 친구들’을 통해 최초로 ‘쿠치카’의 집단전기를 펼쳐냈다.

강력한 소수, 쿠치카의 멤버는 밀리 발라키레프·알렉산드르 보로딘·니콜라이 림스키 코르사코프·체자리 큐이, 그리고 월시의 견해에 따르면 이 그룹의 창의적 원동력이었던 모데스트 무소륵스키.

1855년 처음으로 상트페테르부르크에 온 발라키레프는 ‘제2의 글린카’로 불린다. 18세에 부유한 후원자를 만나 작곡을 시작한 발라키레프의 문제는 다름 아닌 ‘공연’을 혐오하는 것이다. 그는 “사람들 앞에서 그런 행위(연주)를 하고 내려올 때마다 도덕적 모욕감을 느낀다”라며 투덜거렸다.

1859년, 쿠치카의 또 다른 두 멤버가 상트페테르부르크에 오게 된다. 무소륵스키와 보로딘이 각각 근위병과 의사의 신분으로 병원에서 만난 것이다. 무소륵스키는 본인의 잦은 자위행위 때문에 야기되었다고 여기던 우울증을 극복하고, 군대를 떠나 발라키레프와 음악공부를 시작한다. 월시의 글에 따르면, 무소륵스키는 “육체적으로 누군가에게 헌신하기가 두려운, 불안한 이성애자”의 상태였다. 이토록 침울하고 죄책감에 시달리며 충동적인 무소륵스키는 훗날 러시아 음악 부활의 원동력이 되었다.

이후 3년, 보로딘 역시 발라키레프에게 음악을 배우게 됐으며, 어린 해군사관 후보생이던 림스키 코르사코프는 피아노 악보를 들고 발라키레프의 현관문을 두드렸다. 체자리 큐이도 글린카의 집에서 발라키레프를 만났다. 러시아 5인조는 그렇게 완성됐다.

이제 그들에게 필요한 것은 하나의 사명감이었다. 그것을 불어넣어준 이가 있었으니, 변호사 출신 음악평론가 블라디미르 스타소프였다. 스타소프는 발라키레프를 시골 등지로 보내 민요를 수집하게 했다. 러시아는 자신의 뿌리를 돌아보아야 하며, 더 이상 시간을 허비할 수 없다는 소신에서였다. 같은 시기, 베르디와 바그너의 작품들이 또 다른 변호사 출신 음악평론가 알렉산드르 세로프의 극찬 속에 상트페테르부르크에서 공연되고 있었다. 스타소프는 세로프의 누이와의 사이에서 사생아를 낳았으며, 이는 신흥 러시아 문화의 배타적 성질을 잘 반영하는 하나의 상징이었다.

1867년 5월, 스타소프는 “작지만 이미 강력한 러시아 음악인 집단(쿠치카)”의 탄생을 발표한다. 스타소프의 라이벌이자 자신의 뜨뜻미지근한 작품들이 쿠치카에게 외면당한 바 있는 세로프는 그들을 맹렬히 비난했다.

그는 쿠치카에 대한 반동 분위기를 조장하며 자신을 지원해줄 이들을 찾았다. 그중 한 명이 바로 소설가 이반 투르게네프였다. 파리에서 러시아를 방문한 그는 쿠치카를 이렇게 언급했다. “얼마나 형편없는 음악, 무(無) 그 자체, 평범함의 극치인가. 이런 악파의 작품을 감상하러 러시아까지 올 가치가 없다.” 혼란을 느낀 젊은 작곡가들은 민족음악에서 낭만적 오리엔탈리즘으로 방향을 전환하고, 그중 가장 많이 알려진 작품이 발라키레프의 ‘이슬라메이’와 림스키 코르사코프의 ‘셰에라자드’ 등이다.

이제 러시아 음악은 새로운 영감의 소스로 무소륵스키를 바라본다. 쿠치카의 마음 불안정한 이 막내는 플로베르의 소설을 오페라로 만드느라 한창 고심 중이다. 오늘까지도 그의 최고 야심작으로 꼽히는 12분 길이의 교향시 ‘민둥산의 하룻밤’은 발라키레프에게 혹평만 듣는다. 어머니의 죽음은 그가 알코올 중독에 빠지는 계기가 된다.

29세의 무소륵스키는 러시아에서는 첫선을 보이는 바그너 오페라 ‘로엔그린’을 관람하면서 그의 소명을 찾고, 알렉산드르 푸시킨의 비교적 덜 알려진 작품 중 서사 드라마 ‘보리스 고두노프’를 발견한다. 이 작품은 러시아 역사에서 라이벌 관계에 놓인 통치자들과 황태자 시해 등 격변의 시대를 그리고 있다. 푸시킨의 희곡은 너무 많은 등장인물과 위험한 정치적 암시 등으로 한 번도 무대에 오르지 못하던 작품이었다. 1년 후, 무소륵스키는 동명의 오페라 ‘보리스 고두노프’를 완성한다.

발라키레프는 이 작품에 대해 쓴소리를 하고, 림스키 코르사코프는 자신의 오페라 ‘프스코프의 처녀’에 나오는 주제가 이 작품에 똑같이 나온다고 주장한다. 무소륵스키는 수정 작업을 거치지만, 마린스키 극장에서 퇴짜를 맞는다. 1872년 새해 첫날, 림스키 코르사코프의 오페라는 마린스키에서 박수갈채를 받는다. 2년 후, 최종 완성판 ‘보리스 고두노프’가 마침내 무대에 올려지자, 사람들의 반응은 극과 극이었다. 대중은 이 오페라의 장엄함에 감동하는 한편 전문 음악인들은 이 작품이 보여주는 소위 ‘순진무구함과 고지식함’에 개탄을 금치 못한 것이다. 러시아 음악계의 신예 표트르 일리치 차이콥스키는 이 작품을 “가장 비도덕적이며 천박한 음악의 패러디”라 일컬었다.

무소륵스키는 이 작품을 철수시키고, 과음으로 사망한다. 15년 후인 1896년, 림스키 코르사코프에 의해 수정된 ‘보리스 고두노프’가 무대에 재등장하며 러시아 음악 레퍼토리의 빼놓을 수 없는 대표작이 되었다. 하지만 그때는 차이콥스키가 이미 여러 오페라와 심포니를 선보이고 국제적 어필에 성공하며 반세기를 걸쳐온 러시아 음악의 본질과 정체성에 대한 논쟁을 불식시켜버린 뒤였다.

유려하고 흥미진진하며 혹은 과하게 자세하기까지 한 월시의 해설을 읽다 보면, 때로는 대체 무엇이 그렇게 문제였는지 고개를 갸우뚱하게 된다. 결국 러시아 음악계에 필요했던 것은 차이콥스키 같은 포퓰리스트 천재가 나타나 러시아 음악을 유명하게 만들어 주는 것뿐이었다. 오늘날 쿠치카 멤버들은 각자 두세 작품 정도로밖에 알려져 있지 않다. 1918년 사망한 큐이의 작품은 거의 연주되지 않으며, 림스키 코르사코프의 오페라들 역시 너무 오랫동안 공연되지 않아 발레리 게르기예프가 1990년대에 마린스키에서 다시금 무대에 올리며 내게 이런 말을 했을 정도였다. “현재 살아있는 사람 중에 림스키 코르사코프의 오페라를 본 사람이 거의 없기 때문에, 과연 무대에서 이 작품이 성공할지 여부를 알 길이 없습니다.”

월시는 20세기 스트라빈스키·프로코피예프·쇼스타코비치의 시대를 수용할 수 있었던 것은 차이콥스키의 성공보다도 쿠치카의 업적 덕분이었다고 설득력 있는 주장을 펼친다. 월시에 따르면 스트라빈스키는 림스키 코르사코프의 제자로 “진정한 쿠치카인으로서 음악 인생의 첫발을 디뎠다.” 무소륵스키의 영향은 드뷔시와 라벨을 통해 프랑스 전통음악에 스며들었다. 발라키레프의 초기 음악은 홀스트와 본 윌리엄스 같은 영국 교향곡 작곡가들의 전통음악 부흥운동에 영향을 끼쳤다. 다시 말해 쿠치카는 절대 내향적이거나 무의미한 그룹이 아니었다.

‘무소륵스키와 친구들’은 여러 가지 독창적인 통찰을 제공하지만 새로운 발견은 거의 없다. 저자 월시가 기존의 음악학 서적들에 거의 의존하고 있기 때문이다. 동료 음악학자들의 말을 얼마나 많이 인용했는지, 강력하면서도 그렇기에 논란을 빚기도 하는 리처드 타루스킨의 글은 장장 26 쪽에 걸쳐 거의 아부에 가까울 정도로 참조했을 정도니 말이다. 이런 트집거리만 제외하면, 지금 만큼이나 러시아 문화의 본질을 괴롭게 하던 고뇌와 불안감에 대한 길잡이적 연구를 통해 우리가 배울 점이 상당하다.

번역 윤수린

Small but Mighty, Kuchka

노먼 레브레히트 칼럼의 영어 원문을 함께 제공합니다

Russian music begins with an Irishman, John Field, who migrates to St Petersburg in 1803. Among his pupils is Mikhail Glinka, a landowner’s son who, scorning the drawing-room diversions that help pass the long Russian winters, writes two epic operas in the 1830s: “A Life for the Tsar” and “Ruslan and Lyudmila.”

Depressed by poor performances, he gives up. It’s more than one man can do to awaken Russia from musical torpor. It takes, in fact, a clutch of composers?a mighty handful, or kuchka, as they are called. Stephen Walsh’s new book, “Musorgsky and His Circle,” remarkably, is their first collective biography.

The group are Mily Balakirev, Alexander Borodin, Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov, Cesar Cui and?the driving creative force, in Mr. Walsh’s view?Modest Musorgsky. Balakirev, arriving first in St. Petersburg in 1855, is dubbed “a second Glinka.” At age 18, he finds a rich patron and starts to compose. His problem? He hates giving concerts. “I feel morally defiled after every such public act,” he grumbles.

Next in town, in 1859, are a guards officer and a medical doctor?Musorgsky and Borodin?who meet on duty at an army hospital. Musorgsky is out of uniform and studying with Balakirev after overcoming a deep depression, brought on, he thinks, by masturbation. He remains, writes Mr. Walsh, “an uneasy heterosexual nervous of physical commitment.” Morose, guilt-ridden and impulsive, Musorgsky becomes the engine of Russia’s musical regeneration.

In the next three years, Borodin finds his way to Balakirev for musical instruction, and a young naval cadet named Rimsky-Korsakov shows up at Balakirev’s door with a piano score in hand. C?sar Cui, an engineering graduate, meets Balakirev at Glinka’s. The group is complete.

What they need is a sense of mission. It comes from a lawyer-turned-music-critic, Vladimir Stasov, who sends Balakirev out into the countryside to collect folk tunes. Russia must look to its roots, he proclaims. There is no time to waste. Verdi and Wagner are being staged in St. Petersburg, championed by another lawyer-critic, Alexander Serov. Stasov has a child out of wedlock with Serov’s sister, a symbol of the incestuous nature of emerging Russian culture.

In May 1867, Stasov announces the birth of “a small but already mighty kuchka of Russian musicians”. The kuchka is denounced by his rival Serov, who resents the movement’s exclusion of his own tepid compositions. He rallies a reactionary resistance and finds support from the novelist Ivan Turgenev, who, visiting from Paris, declares: “What terrible music, sheer nothingness, sheer ordinariness. It’s not worth coming to Russia for such a ‘Russian School.’?” Confused, the young composers retreat from Russian ethnicity to romantic orientalism. Balakirev will write “Islamey,” Rimsky-Korsakov “Scheherazade.”

Russian music now looks to Musorgsky for inspiration. The unstable youngest member of the group has been struggling with an opera on a Flaubert novel. His “Night on a Bald Mountain,” at 12 minutes long his most ambitious piece to date, is scorned by Balakirev. His mother’s death turns him into an alcoholic.

Aged 29, Musorgsky attends the Russian debut of a Wagner opera, “Lohengrin,” and finds his calling. From the lesser-known works of Alexander Pushkin he retrieves an epic drama, “Boris Godunov,” depicting a turbulent era in Russian history involving rival dynasties and possible regicide. The Pushkin play has never been performed due to its bewildering number of characters and its dangerous political allusions. Within a year Musorgsky has an opera, fully orchestrated.

Balakirev condemns it; Rimsky-Korsakov detects themes from his own opera in progress, “The Maid of Pskov.” Musorgsky undertakes a revision. It is rejected by the Mariinsky Theater. On New Year’s Day 1872, Rimsky-Korsakov’s opera is acclaimed at the Mariinsky. Two years later, the full “Boris Godunov” is finally staged, provoking a schism between large parts of the audience, who are overwhelmed by its grandeur, and large parts of the music profession, which deplores its supposed naivete. The rising star of Russian music, Piotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky, calls it “the most vile and vulgar parody on music.”

Musorgsky withdraws the opera and drinks himself to death. A revision, made by Rimsky-Korsakov, is staged 15 years later, in 1896, becoming a staple of the repertory. By this time, however, Tchaikovsky has presented a string of operas and symphonies of unqualified international appeal, rendering half a century of bitter arguments over the nature and identity of Russian music altogether redundant.

Reading Mr. Walsh’s fluent, entertaining if overdetailed narrative, you wonder at times what the fuss was about. All Russia needed, musically, was a populist genius like Tchaikovsky to put it on the map. As for the kuchka, each is known by no more than two or three works. Cui, who died in 1918, is barely performed at all, and the Rimsky-Korsakov operas were shelved for so long that, when Valery Gergiev revived them at the Mariinsky in the 1990s, he told me there was no way of knowing if they would work on stage, as hardly anyone alive had seen them.

Yet Mr. Walsh argues convincingly that it is the kuchka’s story, more than Tchaikovsky’s success, which enabled Russia to embrace the 20th century?the age of Stravinsky, Prokofiev and Shostakovich. Stravinsky, a Rimsky-Korsakov pupil, “starts out as a true kuchkist,” according to Mr Walsh. Musorgsky’s influence penetrated the vernacular of French music through Debussy and Ravel. Balakirev’s early music influenced the folk-based revivalism of the English symphonists Holst and Vaughan Williams. The kuchka was neither inward-looking nor futile.

“Musorgsky and his Circle” offers many original insights but few discoveries. Mr Walsh relies mostly on published musicology, quoting academic colleagues so generously that the powerful (and divisive) Richard Taruskin is referenced on no fewer than 26 pages, a kind of hat-tipping that verges on obsequiousness. These cavils aside, there is much to be learned in this illuminating study of the dark preoccupations and insecurities that beset the heart of Russian culture, then as now. NL