음악과 유대인, 무한의 가능성

Music and the Jews, Infinite Possibilities

바이로이트를 방문한 한 이스라엘 작곡가는 이렇게 외쳤다.

“바그너가 옳았다! 우리는 그들과 음악을 듣는 방식 자체가 다르다.”

칠흑 같은 깊은 밤, 나는 사파드에 위치한 어느 한 묘지의 자갈길을 걷는다. 이 곳은 여느 묘지가 아니다. 성지 중의 성지일 것이다. 등도 없는 이 길의 끝에는 유대교에서 강력한 영향력을 지녔던 두 인사, 신비주의와 율법주의의 마스터, 바로 ‘거룩한 사자’로 불리는 이사크 루리아와 ‘요세프지파’로 불렸던 요세프 카로가 잠들어 있다.

나란히 위치한 무덤 앞, 촛불 하나가 깜빡인다. 내 동행자 이얄 실로아가 바이올린을 꺼내 든다. 이얄은 런던 심포니 오케스트라 단원으로 활동하다 신앙을 받아들이면서 일을 그만두었다. 그는 예루살렘의 제2성전에서 레위인들이 부르던 노래라며 곡을 하나 연주하기 시작한다. 서로 눈빛을 교환하는 우리는 그의 설명이 사실이 아니라는 것을 알고 있다. 멜로디의 조성이나 색깔, 리듬 모두 19세기 초기 동유럽의 특색이 짙게 배어 있기 때문이다. 그래도 이 곡이 전통적으로 성전음악이라는 사실은 변함없기에 전통에 대한 논쟁의 여지는 없다. 우리는 지금 이사크 루리아의 신비주의와 요세프 카로의 철저한 율법주의의 분열점에 서 있다.

이곳은 이스라엘. 나는 BBC 라디오의 시리즈 프로그램 ‘음악과 유대인(Music and the Jews)’에 사용할 증거 자료를 수집하고 있다. 내가 찾는 것은 유대음악이 아니다. 클레즈머 밴드나 하시드 노래, 칸토리얼 멜리스마, 라디노 발라드 등을 주류로 하는 장르가 반영하는 유대 정통성의 정도는 단지 청어 피클의 그것에 지나지 않기에, 이 장르에 대한 자세한 묘사는 크게 필요 없다고 생각한다. 위의 장르들은 유대인들이 각자 흩어져 거주하는 지역에서 그곳의 특색을 답습해 자신들의 색깔을 입힌 것이다. ‘음악과 유대인’이 좇는 이야기는 좀 다르다. 이 프로그램은 음악이 어떻게 역사와 유대인들의 정체성을 형성했는지, 그리고 유대인들이 다양한 음악 형태의 변천에 어떤 영향을 끼쳤는지를 탐구한다.

사실 이러한 접근법을 시도한 건 내가 처음이 아니다. 1905년, 아브라함 츠비 이델손이라는 성가대 선창자가 남아프리카에서 예루살렘으로 건너왔다. 그리고 예루살렘에는 지구촌 곳곳에서 각자 전수 받은 버전의 토라 캔틸레이션을 간직한 노인들이 가득 모여 있다는 사실을 발견했다. 이델손은 곧 버르토크가 발칸 지역에서 한 것과 같은 작업에 착수했다. 자기 녹음 기계에 노인들의 노래를 녹음한 것이다. 녹음 자료를 분석한 결과, 그는 예멘 사람들의 전통이 가장 오래되었고, 그들의 음악적 전의에는 초기 그레고리오 성가와 상당한 유사성이 있었으며, 그러므로 크리스천들이 부르던 노래는 유대 성전음악이었다고 추론했다. 이 가설은 엄청난 논란을 일으켰다. 이후 아델손은 연구에서 손을 떼고 작곡에 몰두해 이스라엘 춤곡 중 가장 유명한 ‘하바 나길라’를 탄생시켰다. 이 작품은 루마니아 민속 춤곡의 곡조를 인용하고 있다.

나는 예루살렘 국립음향자료관에서 축음기를 통해 이델손이 수집한 노래들을 몇 곡 들어보았다. 또한 엄청난 음악 수집가였던 로버트 라하만이 모아놓은, 훨씬 더 특이한 곡들도 들었다. 라하만은 히틀러 정권이 자신의 수집 프로젝트에 필요한 녹음용 왁스 지원을 중단하자 병원에서 버리는 엑스레이 필름에다 노인들의 노래를 녹음한 인물이다. 덕분에 나는 사람의 늑골이 비치는 그 셀룰로이드 디스크를 직접 만져봤다.

탐구는 계속된다. 미국 작곡가 스티브 라이히는 명작 ‘테힐림’을 쓰기 전, 예루살렘에서 예멘 출신의 현인과 공부했다. 이스라엘-예멘 출신 아티스트 아히노암 니니는 2009년 유로비전 송 콘테스트에서 팔레스타인 출신 미라 아와드와 함께 퓨전 송을 연주했다. 아히노암은 헤르즐리아 해변 가까이 위치한 자신의 집에서 내게 예멘 음계, 그레고리오 음계, 중세 이탈리안 음계를 통합하는 멜로디를 무반주로 불러준다.

이 모든 탐구로 이르는 곳은 과연 어디일까? 유대 정체성의 본질이다. 4천 년에 이르는 유대의 역사는 이집트와 시나이, 이스라엘과 바벨론, 이스라엘과 디아스포라 등 추방과 구원이라는 사이클의 반복이다. 양피지 두루마리에 깃펜으로 쓰인 토라는 유대인들의 존재성 유지에 있어 반드시 넘어야 할 험한 산과도 같은 존재였으며, 토라의 의미는 오늘날도 크게 다르지 않다. 하지만 출판 기술이 발달하고 대중이 글을 깨우치기 전까지만 해도 동물의 피부에다 글을 남기는 것은 문화적 유산을 보존하는 데 있어 절대 영구적으로 안전한 방법일 수 없었다. 또한 기억은 절대적이지 못하며 두루마리 종이는 쉽게 불에 타버린다. 글은 그렇게 사라질지언정 음악은 오래도록 살아남아 전해진다.

5세기 무렵, 마소라테스(‘마소렛(masoret)’은 ‘전통’을 뜻하는 히브리어다)라 불리는 랍비들이 티베리아스에 모여 성서에 쓰인 모든 문장에 대한 음악적 전의 또는 사인을 통일하고 고착시켰다. 오늘날에도 유대인들이 모여 기도하는 곳이면 어디든 이 노래들이 불리고 있다. 물론 곡조는 각자 거주하는 지역 문화의 영향으로 크게 다르다. 일례로 독일계 유대인들의 곡은 일반적 음조로, 이라크계 유대인들이 부르는 곡은 미분음조로 되어 있다. 그러나 이 토라를 노래하는 곡들이 장소와 문화를 불문하고 공통적으로 일치하는 부분이 있다. 체계와 프레이징이다. 유대인들은 기보법을 통해 망각을 피할 수 있었다.

유대인들은 이러한 교훈을 마음에 새기며 음악을 자기 문명의 방어 도구로 여기게 되었다. 1492년에는 스페인, 1497년에는 포르투갈에서 쫓겨나면서 그들은 자신들의 신조 혼합언어 ‘라디노’에 이베리아의 멜로디와 예배의식을 담아 나왔다. 러시아 제국의 압박 속에, 그들은 러시아의 테마를 흡수해 유대적 특수성을 입혔다. 1812년 프랑스 침략군의 행군 노래에는 ‘나폴레옹 니군(나폴레옹 노래)’이라는 이름을 붙였으며, 종교의식의 정점인 속죄일에는 ‘루바비치 하시딤’이라는 유대종교운동단체가 이 노래를 부르기도 했다.

유대인들의 유럽 음악에 대한 접근은 교회와 국가의 강한 반대에 부딪혔다. 포스트 나폴레옹 시대에 이르러 베를린의 마이어베어와 멘델스존이 저항 불가능한 엄청난 영향력으로 각각 오페라와 교향악의 세계에 돌풍을 일으켰다. 이후 두 세대 안에 구스타프 말러는 빈 오페라의 개혁을 일으켰고, 아르놀트 쇤베르크는 서양의 숨막히는 음악적 규범을 깨뜨리며 자유로운 무조주의를 소개했다.

뉴욕 동남부 지방에서는, 러시아 유대인 대학살의 피난민들과 한때 플랜테이션 노예였던 유대인들의 후손들이 단조 곡에서 ‘블루 노트’를 부르는 자신들의 취향을 가지고 대중음악계를 뒤흔들어 놓았다. 퓨전의 귀재 조지 거슈윈이 자신의 테마 중 ‘프리지시(freygish)’라고 부른 곡조들은 탈무드 수업에서 질문할 때 부르는 멜로디로, 음악학자들은 아마 거슈윈이 프리기아 선법을 의미하는 것일 거라고 추정했다. 거슈윈은 ‘성경에 대한 회의주의? 꼭 그렇지만은 않다(Bible-sceptical It Ain’t Necessarily So)’라는 작품에서 자기 선조들의 문명에 대한 칭송과 도전을 동시에 하고 있다.

유대인의 서양음악 합류에 대한 반감은 급증했고, 이는 리하르트 바그너의 작품에서 보여지는 과격한 표현과 히틀러 정권하에 있던 유럽 국가들의 폭력적인 반응 등에서 여실히 반영됐다. 유대인들은 음악적 독창성이 결여되어 있으며 대중의 취향을 바꿔놓는다는 비난을 받았다. 이런 비난은 어느 정도 사실이다. 엔터테인먼트 시대에 태어난 마이클 그레이드는 유대인들이 역사로부터 대중적 분위기보다 한 발 앞서가야 한다는 교훈을 배웠으며, 그 교훈을 발판 삼아 음악 비즈니스를 일구어냈다고 주장하지만, 이에 대한 반발 역시 만만치 않다.

바이로이트를 방문한 한 이스라엘 작곡가는 이렇게 외쳤다.

“바그너가 옳았다! 우리는 그들과 음악을 듣는 방식 자체가 다르다.”

말러 교향곡은 서로 상충되는 해석들을 낳으며, 에이미 와인하우스의 노래는 가수 자신보다도 훨씬 더 오래된 슬픔을 표현하고 있다. 음악과 유대인의 상호작용은 원시적이고 모호한 형식과 무한한 가능성에 대한 신비스런 일별의 풍부한 결합이다.

번역 윤수린

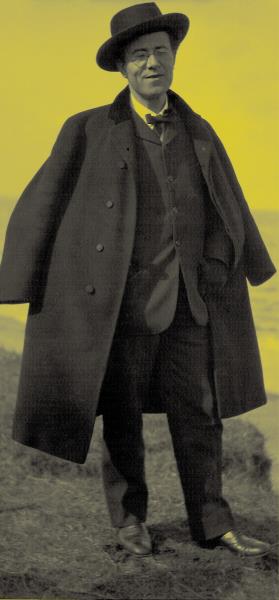

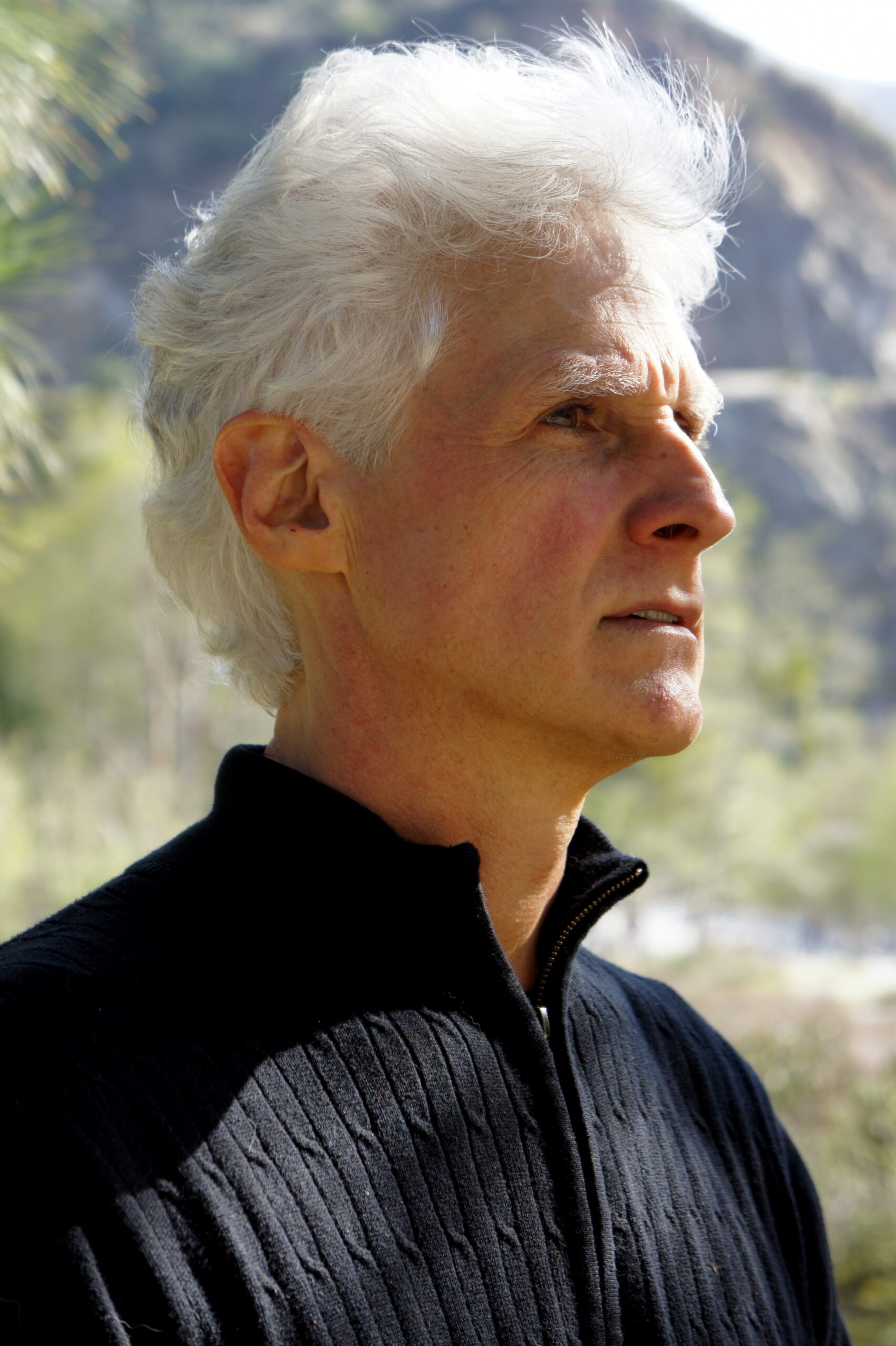

글_노먼 레브레히트

Music and the Jews, Infinite Possibilities

노먼 레브레히트 칼럼의 영어 원문을 함께 제공합니다

It is pitch dark, dead of night, in Safed and my feet are crunching gravel in a graveyard. Not any cemetery. Perhaps the holiest in the Holy Land. At the end of this unlit path lie side by side the twin propulsive forces in Judaism, the great masters of mysticism and legalism, the Holy Lion and the House of Joseph.

A candle flickers at the foot of the adjacent tombs. My companion, Eyal Shiloach, takes out his violin. Eyal used to play in the London Symphony Orchestra until he was drawn to the light of faith. He starts a tune that he tells me was sung by Levites in the Second Temple in Jerusalem. Both he and I know, exchanging glances, that this cannot be true: tonality, colour and pulse place the melody in eastern Europe, early 19th century. But tradition holds that it is Temple music and there is no arguing with tradition. We stand riven between the mysticism of the Holy Lion (Isaac Luria) and the meticulous rationalism of the House of Joseph (whose surname was Caro).

I am in Israel, gathering testimony for a BBC Radio 3 series titled Music and the Jews. Not Jewish music, note. There is insufficient reason, in my view, to delineate a genre whose main streams — klezmer bands, Chasidic songs, cantorial melismas, Ladino ballads — are no more Jewish than pickled herring. Each is a local catch, harvested and embellished by Jews in the lands of their dispersion. Music and the Jews pursues a different story. It explores how music shaped the history and identity of the Jews, and how Jews influenced the course of music in all its forms.

I am not the first on this trail. In 1905, a cantor called Abraham Zvi Idelsohn arrived in Jerusalem from South Africa and found the streets paved — or squatted — by old men from all corners of the earth, each with his native cantillation for singing the Torah. Idelsohn set to work, like Béla Bartók in the Balkans, recording fragile voices on a wire machine. Analysing the results, he concluded that Yemenites had the oldest traditions and that their tropes bore such affinity to early Gregorian chant that it was likely Christians were singing music of the Temple. All hell broke loose at this hypothesis. (Idelsohn went on to compose an Israeli dance, Hava Nagila, the most popular of its kind. The melody is Romanian.

At the National Sound Archive in Jerusalem I spun some of Idelsohn’s cylinders, as well as much weirder items by the obsessive Robert Lachmann who, when Hitler’s Reich stopped supplying wax for his project, recorded old men’s chants on discarded hospital X-rays. I have handled a celluloid disc with the shadow of human ribs on it.

The quest continues. The American composer Steve Reich studied with a Yemenite sage in Jerusalem before writing his masterwork, Tehillim. The Israeli-Yemenite artist Ahinoam Nini performed a fusion song with Mira Awad, a Palestinian, at Eurovision 2009. In her house near Herzlia beach, Ahinoam sings for me a capella a melody that unites Yemenite, Gregorian and medieval Italian modes.

Where is this leading? Towards an essence of Jewish identity. The 4,000-year history of the Jews is a recurrent cycle of exile and redemption: Egypt and Sinai, Israel and Babylon, Israel and diaspora. The Torah, inscribed by quill on parchment scrolls as it is to this day, was the crucible of a continuing Jewish existence. But in an age before printing and mass literacy, writing words on animal skin was never going to be a safe enough way to conserve heritage. Memory is fallible and scrolls flammable. When text fades, however, music still endures.

So around the fifth century, a group of rabbis known as Masoretes (masoret is Hebrew for tradition) gathered in Tiberias to pin tropes, or musical signs, to every word of holy writ. These tropes are still sung wherever Jews gather to pray. The tune varies considerably, influenced by the host culture. In a German community it will be tonal, among Iraqis microtonal. The system, though, remains the same and the phrasing is identical wherever Torah is sung. Musical notation saved the Jews from oblivion.

Bearing that lesson in mind, Jews came to regard music as a defence mechanism for their civilisation. Evicted from Spain and Portugal in 1492 and 1497, they carried away a bevy of Iberian melodies and liturgies in their hybrid language, Ladino. Oppressed in the Russian Empire, they absorbed indigenous themes and gave them a Jewish specificity. A march song of the invading French army in 1812 was renamed the Napoleon Nigun and sung by Lubavitch Chasidim at the climax of their religious devotions, the end of Yom Kippur.

The entry of Jews into European music was resisted by Church and state until the post-Napoleonic era, when two Berliners, Meyerbeer and Mendelssohn, burst into opera and symphonic music with irresistible force. Within two generations, Gustav Mahler was reforming the Vienna Opera and Arnold Schoenberg had torn off the tonal corset of the western canon, replacing it with a liberated atonality.

On New York’s Lower East Side, sons of Russian pogrom refugees and former plantation slaves turned a common tendency to sing “blue” notes in minor keys into an industry of popular music. George Gershwin, a genius of fusion, named some of his themes as “freygish” — the interrogative melody of Talmud study (musicologists thought he meant the Phrygian mode). In the Bible-sceptical It Ain’t Necessarily So, Gershwin simultaneously exalts and challenges his ancestral civilisation.

Resistance to the upsurge of Jews in music found violent expression in Richard Wagner’s writings and violent reaction in Hitler’s Europe. Jews were accused of lacking musical originality and remoulding public taste. There is a grain of truth in these charges. Michael Grade, born into an entertainment dynasty, maintains that Jews invented the music business because their history had taught them to be one step ahead of the popular mood, ugly as it might turn.

An Israeli composer, visiting Bayreuth, exclaims: “Wagner was right! We don’t hear music in the same way as they do.” A Mahler symphony is open to conflicting interpretations. An Amy Winehouse song exposes a grief older than her own. The interaction of music and the Jews is a fertile engagement of primal, nebulous forms, a mystic glimpse of infinite possibilities. NL