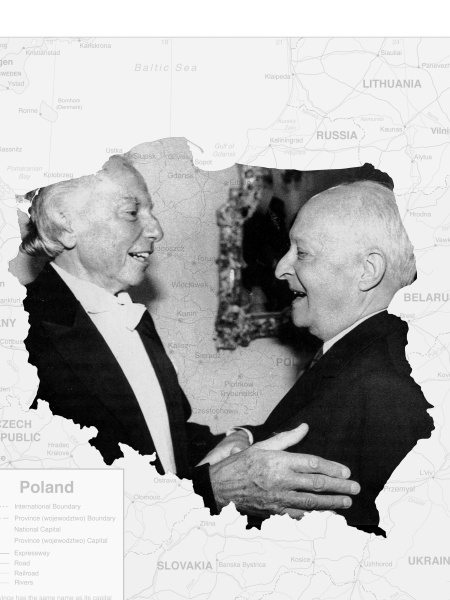

폴란드를 대표하는 20세기 작곡가 루토스와프스키와 파누프니크가 지난해와 올해, 각각 탄생 100주년을 맞이했다

만약 2013년 음악계의 초점이 바그너와 베르디, 브리튼이 아니었다면 우리는 보다 난해한 문제를 놓고 심사숙고하지 않았을까 싶다. 그 문제는 다름 아닌 ‘폴란드 음악이란?’

이 난제의 답을 찾기 위해 고민하던 두 음악인 비톨트 루토스와프스키와 안제이 파누프니크가 작년과 올해 각각 탄생 100주년을 맞았다. 그리고 세 번째 음악인 안드레이 차이콥스키는 지난 여름 중요한 오페라 초연을 통해 대중의 기억으로 돌아왔다. 이 세 명의 음악인은 분할점령시대의 폴란드는 어떠했는지, 그리고 오늘날 폴란드가 주는 의미는 무엇인지에 대한 우리의 이해와 생각에 큰 영향을 준다.

핀란드를 비롯한 소수의 민족국가 중 하나인 폴란드는 자국 음악인들의 작품을 통한 ‘음악적 성명’에 의해 가장 잘 정의된다. 쇼팽은 파리로 망명한 후 독립을 향한 울부짖음을 오롯이 그의 음악으로 표현했다. 이는 수많은 후대 음악인들로 하여금 사실상 존재하지 않았던 ‘타락 전 파라다이스’에 대한 허구적 향수를 갖게 했다.

1919년 파리강화회의. 갓 독립을 찾은 폴란드를 대표해 총리이자 걸출한 피아니스트 이그나치 얀 파데레프스키가 참석했다. “당신은 그 위대한 피아니스트 파데레프스키가 아닙니까?” 프랑스 총리 조르주 클레망소가 외쳤다. “네, 그렇습니다 총리님.” “아, 이게 무슨 일인가요….” 그 당시 파데레프스키는 자국이 몰락의 길로 치닫는 것을 깨닫지 못했지만, 이후 그의 꿈은 결국 국가의 내부적 갈등과 불화로 퇴색되고 독일의 제2차 침입으로 인해 무너졌다. 그의 음악은 쇼팽과 마찬가지로 19세기 전통적 낭만적 민족주의를 고수했다. 그 다음 세대 카롤 시마노프스키의 복잡하고 개별화된 스타일은 애국적 열망이 부재하다는 이유로 비난받았다.

1945년 이후, 그러한 열망은 소련에 대한 해방으로 모아졌다. 나치 점령 시절 불법 카페 등지에서 네 손을 위한 연탄곡을 연주하던 두 친구 루토스와프스키와 파누프니크는 (그들의 연탄곡 악보는 모두 여러 번의 봉기로 인한 화재 속에 사라졌으며, 현재까지 보존된 악보는 ‘파가니니 변주곡’이 유일하다) 독일군이 물러나자 곧바로 작곡 활동을 재개했으나 이내 소련 공산당원들의 감시 대상이 되었다. 둘은 극심한 통제 속에서도 최선을 다했다. 루토스와프스키가 1954년 발표한 ‘오케스트라를 위한 협주곡’은 표면상으로는 버르토크 헌정 작품이지만 실제로는 금지된 불협화음을 교묘하게 포함시켜 공산체제에 대한 전복적인 메시지를 담고 있다. 파누프니크는 쇼팽에 대한 오마주와 ‘전원 교향곡’을 썼다. 그는 정부의 끊임없는 강요와 간섭에 지쳐 영국으로 망명해 런던 템스 강변에 정착했다.

이후 폴란드 음악은 두 개의 줄기로 갈라졌다. 파누프니크는 모든 현대적 기기를 적극 활용해 9개의 교향곡을 작곡했다. 간결한 구조로 이루어진 이 교향곡들은 카틴 숲 학살사건, 체스토호바의 흑인성모 등 폴란드와 관련된 다양한 이야기를 다루고 있다. 한편 지속적인 정치압력에 시달리던 루토스와프스키는 1960년 해빙 이후 자유로운 작곡 스타일을 만끽했다. ‘베네치아식 유희(Jeux v

nitiens)’에서는 존 케이지의 우연성 기법을 병합했고, 그의 두 번째 교향곡에는 피에르 불레즈의 인상주의 시리얼리즘을 적용했다. 이제 그의 곡에 대한 감독과 평가는 정부가 아닌 카바레 연주자이던 처제의 몫이었다.

폴란드 음악은 두 가지 망명적 양상을 띠고 있다. 대외적으로는 파누프니크, 국내적으로는 루토스와프스키의 경우다. 이 둘은 공식적으로는 공산주의가 붕괴될 때까지 서로 만나지 못했지만, 내가 안드레이에게서 들은 바에 의하면 지속적으로 연락을 주고받았다고 한다.

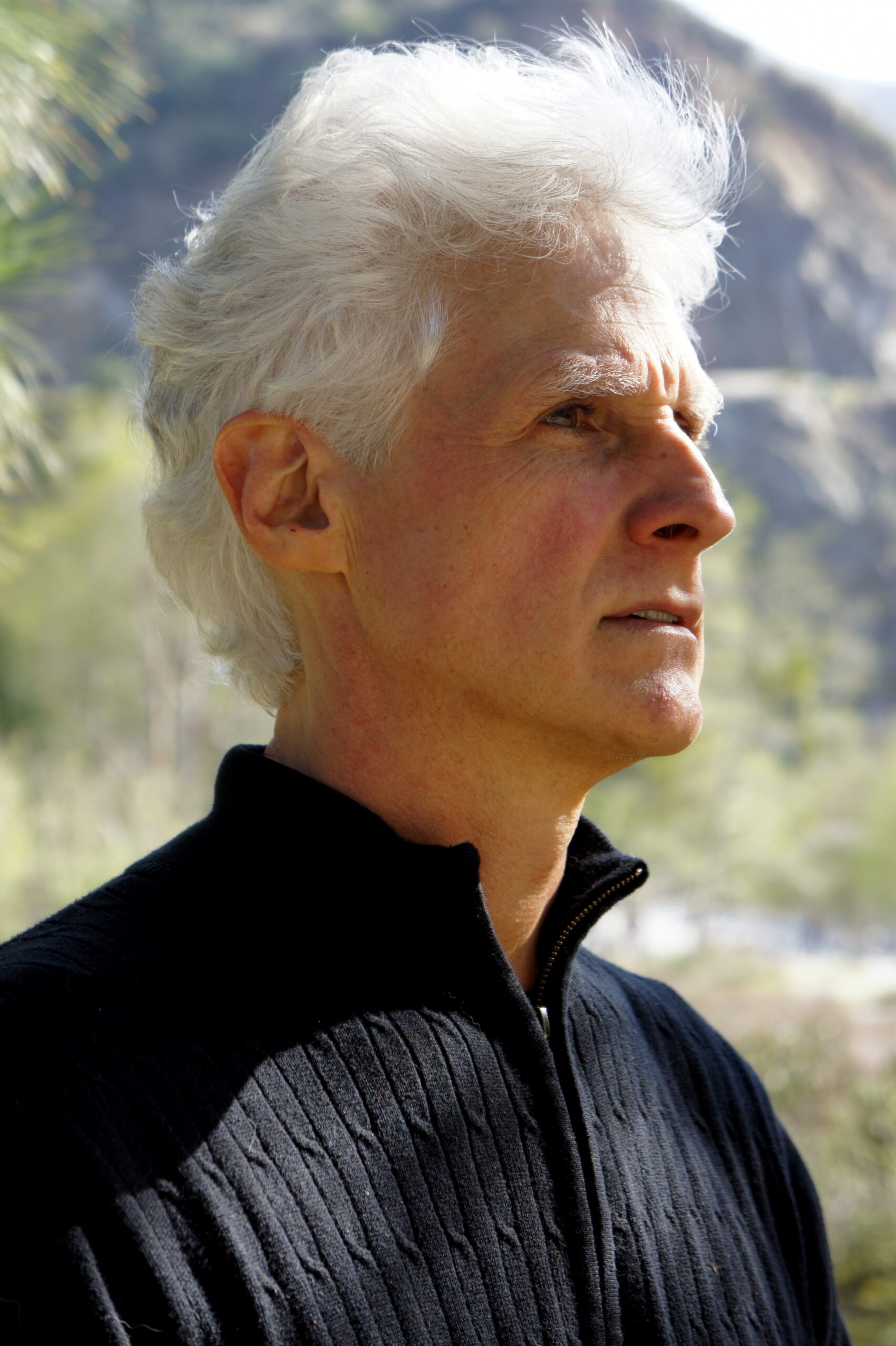

1991년 파누프니크가 사망했고, 3년 후 루토스와프스키가 그 뒤를 따랐다. 그의 음악은 1980년대부터 세계적 음악가인 핀란드 출신 지휘자 에사 페카 살로넨과 독일 출신 바이올리니스트 안네 조피 무터 등을 통해 보다 두터운 청중을 확보하기 시작했다. 루토스와프스키의 음악은 살로넨의 지휘로 로스엔젤레스에서 실황녹음되어 소니 레이블을 통해 발매되었다. 또한 샨도스 음반에 담긴 같은 곡은 에드워드 가드너와 BBC 심포니 오케스트라의 연주로, 절제된 접근법과 소리는 작곡가의 수줍고 모호하며 고집스러울 정도로 정중한 성격을 잘 반영한다. 지휘자가 누구냐에 따른 차이란 실로 엄청나지 않은가.

파누프니크의 심포니들은 CPO 레이블에 꾸준히 실리고 있다. 지휘자는 우카시 보로비치. 베를린의 비교적 덜 알려진 오케스트라를 이끌고 직관적이고 이해하기 쉬운 지휘를 통해 꼼꼼하며 정확한 연주를 선보인다. 지금이야말로 폴란드 음악의 두 줄기를 나란히 놓고 비교해볼 좋은 때가 아닌가 싶다.

파누프니크와 루토스와프스키가 폴란드 음악의 유일한 주류였다는 것은 아니다. 그라지나 바체비치(1913~1969)의 현혹될 정도로 조용한 음악이 주목을 받고 있으며, 위태할 정도로 경건한 헨리크 고레츠키(1933~2010)는 모던 교향곡을 작곡해 기록적인 인기를 끌었다. 한편 폴란드 영화의 재부상은 두 명의 재능 있는 작곡가를 배출했다. 즈비그니에프 프레이스네르 보이체크 킬라르가 그 주인공이다.

그런데 우리가 폴란드 사람들과 마찬가지로 폴란드의 주류음악에 집중하면서 간과하는 또 다른 줄기가 있다. 언급되지 않은, 폴란드 역사의 비기여자, 유대인들의 침묵이다. 이 침묵은 올해 여름 브레겐츠 페스티벌에서 연출가 데이비드 파운트니가 안드레이 차이콥스키의 ‘베니스의 상인’을 세계 최초로 무대에 올리면서 마침내 깨졌다.

유대인 이름이 ‘차이콥스키’라니? 실은 본명이 아니다.

1935년 11월 1일 출생한 그의 본래 이름은 로베르트 안드레이 크라우트하머였다. 그의 할머니가 그의 이름을 러시아 작곡가의 이름으로 바꾸어 붙인 후 함께 바르샤바 게토를 몰래 탈출해 장롱 속에 숨겨두고 키웠다. 그의 어머니는 트레블링카에서 살해되었다. 대회에서 연주로 아르투르 루빈시테인의 귀를 사로잡은 안드레이는 그렇게 콘서트 피아니스트로서 국제적 커리어를 시작했고, 종종 쇼팽과 슈만의 분위기를 풍기는 자작곡들도 선보였다. 피아니스트 스티븐 코바세비치는 그를 가리켜 “우리 세대 최고의 음악가”라고 극찬했다.

안드레이는 1960년 런던으로 이주, 셰익스피어 연극과 동성애에 열정적으로 빠져들었고 수 차례 자살을 시도했으며 1982년 46세의 나이에 대장암으로 사망했다. 그는 세상을 떠나면서 자신의 두개골을 영국 왕립 셰익스피어 극단에 남겼다. ‘햄릿’의 소품으로 사용해달라는 유지였다. 연극배우 데이비드 테넌트가 그 소품을 들고 무대에 등장했다.

셰익스피어의 걸작 ‘베니스의 상인’은 마침내 위대한 작곡가를 만났으나, 단 몇 마디를 남겨두고 그가 눈을 감는 바람에 그대로 묻히는 듯했다. 이 작품을 보거나 들은 사람이 아무도 없었다. 이번 여름 브레겐츠 페스티벌에 올려진 파운트니의 프로덕션은 지금까지 베일에 가려져 있던 여러 면들을 드러냈다. 차이콥스키의 오페라적 재능, 가장 심한 반유대주의를 노래하는 정본판을 통해 유대인 작곡가의 목소리가 오스트리아 땅에서 울려 퍼진다는 사실, 그리고 무엇보다도 크리스천과 유대인의 폴란드 음악을 통한 교감이라는 복잡한 콘셉트는 그 어떤 다른 형태의 폴란드 음악에도 없을 것이다.

올해가 가기 전에 정립되어야 할 것이 있다. ‘폴란드 음악이란, 그리고 21세기의 폴란드란 무엇인가’이다. 과연 우리가 배워온 대로 국수주의자와 국제주의자라는 평행선상의 주요한 두 흐름을 담고 있는 지도일까? 그렇다면 그 지도는 무시해도 무방하다. 하지만 그것이 답이 아니라면, 우리는 지도를 다시 그려야 할 것이다. 막힌 관들과 파묻힌 강들을 아울러서 아주 다른 폴란드를 상상해보는 것이다. 그저 괴팍한 나라라기보다는 이루지 못한 염원으로 가득한, 국가를 위해 살고 국가를 위해 목숨을 바칠 만한 가치가 있는 폴란드. 그렇기에 올해는 그 어떤 기념보다도, 끔찍이도 음악적인 국가의 시대 도래를 기념하는 것이 중요하지 않을까.

번역 윤수린

▲ 글_노먼 레브레히트

영국의 음악ㆍ문화 평론가이자 소설가. ‘텔레그래프’ ‘스탠더즈’ 등 여러 매체에 기고해왔으며, 지금 이 순간에도 자신의 아츠저널 블로그(www.artsjournal.com/slippeddisc)를 통해 음악계 뉴스를 발 빠르게 전한다

What is meant by Polish music?

노먼 레브레히트 칼럼의 영어 원문을 함께 제공합니다

If the musical world were not up to its ears in Wagner, Verdi and Britten, it would quite probably have spent this past year contemplating the more troubling question of what, if anything, is meant by Polish music.

Two men who sought an answer to that conundrum are celebrating back-to-back centenaries ? Witold Lutoslawski last year, Andrzej Panufnik next. A third, Andrei Tchaikovsky, was plucked from oblivion with a major operatic premiere in the summer. Together, they add vastly to our appreciation of what it was to be a Pole in the century of its nationhood, and what it is means today.

Poland, along with Finland and very few other nation-states, is defined by musical statements. The liberation cry was articulated by Frederic Chopin, mostly in Paris. It misled many successors onto a trail of false nostalgia for a prelapsarian paradise that never was.

At the Paris Peace Conference of 1919, newly independent Poland was represented by its first prime minister, the pre-eminent pianist Ignacy Jan Paderewski. ‘Vous-etes Paderewski, le grand pianiste, n’est-ce pas?’ cried Georges Clemenceau. ‘Oui, Monsieur le President.’ ‘Alors, quelle chute….’ Paderewski may not have seen it at the time as a comedown, but he lived to see his dream soured by Polish strife and crushed by a second German invasion. His music, like Chopin’s, clung to 19th century conventions of romantic nationalism. In the next generation, Karol Szymanowski’s complex individualised idiom was condemned for its lack of patriotic zeal. Music in Poland, a vital component in the national interest, was supposed to conform to political expectations.

After 1945, those expectations were harnessed to the Soviet agenda. Lutoslawski and Panufnik, two friends who played four-hand piano at illegal cafes under the Nazi occupation (their Paganini Variations was the only score to survive the final conflagration), emerged unblinking into the Warsaw ruins to find commissars at their shoulder as they resumed composing. Both tried their best under severe constraints. Lutoslawski, in 1954, presented a Concerto for Orchestra that was ostensibly a tribute to Bartok while subversively infiltrating forbidden dissonances. Panufnik, for his part, wrote a Homage to Chopin and a Rustic Symphony. He was sent of to lead a deputation to Mao Zedong before, weary of state interference in his life, he defected to England and settled at Twickenham, on the banks of the River Thames.

The main course of Polish music ran thereafter in two parallel streams. Panufnik, availing himself of every modernist device, wrote nine symphonies whose austere structures revealed a constant preoccupation with Poland ? with the Katyn massacre, the Black Madonna of Czestochowa and more. Lutoslawski, politically inhibited, turned a 1960s thaw to advantage, assimilating the chance theories of John Cage in Venetian Games and the impressionistic serialism of Pierre Boulez in his second symphony, all the while filtering out songs through his sister-in-law, a cabaret artist.

Polish music assumed two forms of exile, external in Panufnik’s case, internal in Lutoslawski’s. Officially they were unable to meet until Communism ended, though I heard from Andrzej that their dialogue continued throughout.

Panufnik died in 1991, Lutoslawski three years later. From the 1980s on, his music earned a much wider audience through the advocacy of such global interpreters as the Finnish conductor Esa-Pekka Salonen and the German violinist Anne-Sophie Mutter. Concurrent recordings of Lutoslawski’s music are appearing on Sony, conducted by Salonen rather loudly in Los Angeles, and on Chandos, where the lower-key approach of Edward Gardner and the BBC Symphony Orchestra sounds to my ear more closely attuned to the composer’s shy, elusive, insistently courteous nature. What a difference a conductor can make.

Panufnik’s symphonies are appearing steadily on the CPO label, played with meticulous fidelity by one of the less-heralded Berlin orchestras and conducted quite intuitively by Lukasz Borowicz. This is a very good time to compare the two streams, side by side.

Not that they were the only tributaries. The deceptively quiet music of Grazyna Bacewicz (1913-69) is gaining attention and the dangerously devout Henryk Mikolai Gorecki (1933-2010) somehow managed to write the most popular modern symphony on record. The resurgence of Polish cinema yielded two potent composers, Zbigniew Preisner and Wojcech Kilar. I shall leave blank space below for you to add any significant Polish voices I have omitted.

Yet, as we assess the mainstream we ignore – as Poles do – the other, the unmentioned, the non-contributor to the Polish story: the Jewish silence. That silence was broken this summer at Bregenz where David Pountney staged the world premiere of The Merchant of Venice by Andrei Tchaikowsky.

A Jewish Tchaikovsky? No, not his real name.

He was born Robert Andrzej Krauthammer on November 1st, 1935, smuggled out of the Warsaw Ghetto by his grandmother under a Russian composer’s name and kept alive for two years in a cupboard.?His mother was murdered at Treblinka. Catching Arthur Rubinstein’s ear at a competition, he began an international career as a concert pianist, often insinuating his own compositions between Chopin’s and Schumann’s. The pianist Stephen Kovacevich called him ‘the best musician of my generation.’

He moved to London in 1960, developed passions for Shakespearian theatre and discreet male friendships, attempted suicide several times and died of colon cancer, aged 46, in 1982. He left his skull to the Royal Shakespeare Company for use as a prop in Hamlet. David Tennant appeared holding it on a Royal Mail first-class postage stamp.

The Merchant of Venice, Shakespeare’s last masterpiece to await a major composer, was left within a few bars of completion at his death. It has never been seen or heard before. Pountney’s production this summer at the Bregenz Festival will take a huge leap into several dimensions of the unknown – Tchaikowsky’s gift for opera, the voice of a Jewish composer in the most anti-Semitic play in the canon, its creation on Austrian soil ? above all, the interaction of Christian and Jew in a Polish creation, a concept so confusing it hardly exists in any form of Polish music.

What will be decided then, before the present year is out, is the very nature of Polish music and, perhaps, of Poland itself in the 21st century. Is it, as we have been taught, a map of parallel main streams, nationalist and internationalist? If it is, it can safely be ignored. If not, we’ll have to rewrite the map, taking in blocked ducts and buried rivers to imagine a very different Poland – more failed aspiration than fractious state, a Poland worth living in and dying for. That’s why, more significant than all other commemorations, this year could mark the coming of age of a terribly musical nation. NL