노먼레브레히트 칼럼 | | SINCE 2012

영국의 평론가가 보내온 세계 음악계 동향

슈타이네커/말러 아카데미 오케스트라

말러는 어떻게 연주해야 하는가

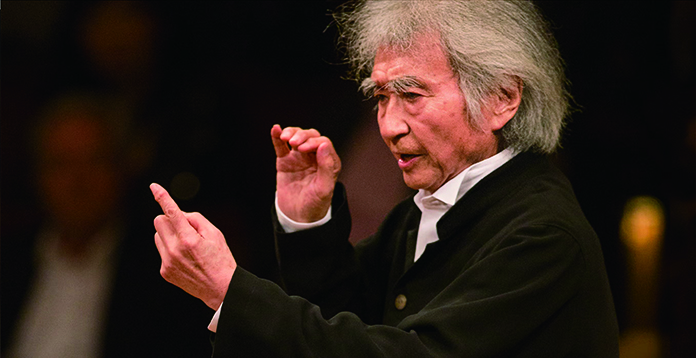

슈타이네커 ©Annemone Taake

시대악기 연주법이 아닌, 시대 정신을 이해하는 것

엘리자베스 2세 여왕이 서거하던 날, 나는 원래 알프스 돌로미테 산맥 위에서 젊은 음악가들이 구스타프 말러(1860~1911)의 교향곡 9번을 시대악기로 연주하는 것을 들을 예정이었다. 1909~1910년 여름, 말러는 마지막 교향곡 두 곡을 토블라흐(도비아코)의 산장 리조트 근처에서 작곡했다. 그는 이 두 곡이 연주되는 걸 듣지는 못했지만, 정확히 어떤 소리로 연주되길 원하는지는 알고 있었다.

말러는 음색에 대해 엄격했다. 빈 오페라 극장의 음악감독이었던 그는 오케스트라의 목·금관악기, 타악기가 R. 슈트라우스의 강렬한 새 오페라와 무조의 가장자리에 위치한 듯 표류하는 자신의 보편주의적 교향곡의 음량, 속도, 정교함에 적합하지 않다고 선언하고 모두 교체했다.

다른 관습은 변하지 않았다. 그의 바이올리니스트는 어깨 받침을 사용하지 않았고, 첼리스트는 짧은 엔드핀으로 연주하며 손으로 만든 비브라토는 적게 하여 무대바닥의 진동을 더 많이 끌어 냈다. 말러가 사용했던 연주회장은 장방형으로, 굴곡성에 맞춰진 현대의 공연장에 비해 더 팽팽한 어쿠스틱 음을 만들어냈다. 말러는 연주회장 상태에 맞춰 모든 연주를 조정했다. 그는 젊은 지휘자 오토 클렘퍼러에게 이렇게 말했다.

“(제 음악이) 잘 안되면 바꾸세요. 그게 당신의 권리, 아니 의무입니다.” 그는 또한 “음악이란 음표 안에 존재하지 않는다”고 즐겨 말하곤 했다. 모든 연주자와 청취자는 어디서 음악을 찾을 수 있을지 생각해야 한다. 말러의 연주에 있어 악기는 그다지 중요하지 않으며 연주하고 듣는 사람이 그 무엇보다 중요하다.

그래서 나는 호기심 가득한 두근거림을 안고 짧은 비행과 환승도 안 되는 기차 두 대를 거쳐 토블라흐에 가려고 짐을 쌌으나, 무릎을 다쳐 소파에 파묻혔다. 여왕(the Queen)의 죽음을 애도하고, 웨스트민스터 사원 앞 대기 줄(The Queue)을 보며 일주일을 보냈다. 사실 그 일주일 동안 내가 정말 원했던 것은 말러의 스타일이었을지도 모를 방식에 최대한 가깝게 연주하는 걸 듣는 것이었다.

슈타이네커의 말러 연주법 발굴기

이 생각을 처음 한 사람은 말러 체임버 오케스트라의 첼리스트 필립 폰 슈타이네커(1972~)로, 그는 대부분의 지휘자가 오해하고 있다고 생각했다. 진정한 말러를 찾아 슈타이네커는 빈 미술사 박물관에 있는 말러의 매입증을 낱낱이 해부하여 그가 주문했던 악기를 찾아 나섰다. 교회 오르간, 골동품점, 군악대의 호른과 오보에를 하나씩 추적해나갔다. 일부는 이베이(eBay)에서 거저 샀으며, 일부는 경매장에서 상당한 금액을 지불하고 구매했다.

1900년대 초반의 악기는 물질적으로 현대의 모델과는 다르다. 금속은 더 얇고, 원통은 더 좁았으며, 조성도 적어 정확도를 내기 어려웠으며 대개는 정확하게 연주할 수 없었다. 사실 말러의 모든 음을 정확하게 낼 필요가 없었다고 가정하는 것이 타당하다. 슈타이네커는 말한다. “놔두면, 악기들은 우리에게 소리에 대해 뭔가를 알려줍니다.”

그는 토블라흐 근처 볼차노에 있는 자신의 아카데미에서 학생들에게 이 이론을 시험해보았다. 그다음에는 말러 체임버 오케스트라 출신 전문 연주자와 말러가 한때 근무했던 빈·프라하·라이프치히·카셀·부다페스트·함부르크·암스테르담·류블랴나 출신 전문 연주자들을 기용했다. 한 해의 대부분의 시간 동안 그는 말러를 어떻게 연주하면 안 되는지에 대한 근본적인 개념을 음악가들에게 쏟아부었다. 그가 주문처럼 되뇌는 말은 다음과 같다. “지난 110년간 악기는 변했습니다.” 우리가 듣는 말러는 사실 말러가 들었던 것과 다른 것이다.

토블라흐에서 연주 중인 슈타이네커와 앙상블

산 위의 여름날, 말러는 무엇을 보았나

말러는 여름 나날을 토블라흐의 텅 빈 나무 오두막에서 무성한 녹음의 계곡과 의사가 오르지 말라고 경고한 매력적인 산길을 바라보기만 하며 보냈다. 심장 이상 진단을 받고, 그는 마지막 교향곡 두 곡을 가까이 다가온 죽음에 대한 암시로 가득 채웠다. 교향곡 9번은 머뭇거리는 리듬으로 시작하여 일부 지휘자들이 말러의 진단에 대한 청진기 소리라 주장하기도 했다(내가 상담했던 심장병 전문의는 터무니없는 소리라며 무시했다). 교향곡 9번에 대한 여타 근거 없는 이야기와 마찬가지로, 내게는 동시대의 악기가 말러의 의도를 더 많이 드러낼 수 있을 것이란 주장이 그럴듯해 보였다.

교향곡은 운명에 맞서며 절대 묵인하지 않는다. 어느 날 독수리 한 마리가 오두막으로 날아들었고 말러는 독수리가 떠날 때까지 피아노 뒤에 웅크린 채 있었다. 이 교향곡에는 자연이 가진 힘에 대한 공포가 있고, 곡의 마지막에서 삶과 죽음의 끊어지지 않는 연속성을 약속하는 초월이 있다. 말러는 우리가 이를 어떻게 받아들이길 의도했을까?

토블라흐 전경

지금, 바로 이 순간에 반응하는 연주

“확실한 건 우리가 절대 모르리라는 점입니다.” 슈타이네커는 이렇게 말했으나, 사운드클라우드(SoundCloud)를 통해 런던에 있는 우리 집 소파로 전달된 토블라흐에서의 시대 악기 연주는 일관되게 시사하는 바가 컸다. 희미한 시작은 오프닝에 놀랍고도 신비한 차원을 더하고, 비브라토 없는 현악은 순간을 에워싸는 즉시성을 만들어낸다. 현악기 연주자들은 말러의 콘서트마스터이자 처남인 아널드 로즈의 초기 음반을 듣고 감상적인 황홀함을 어디에 추가할지 안 것이 분명했다.

플루트와 오보에의 원초적인 리드 소리가 아주 좋았고, 말러의 타악기 주자의 가족이 동물 가죽으로 만든 드럼의 맹공에 상당히 충격받았다. 물론 가장 중요한 본질은 이 명작의 즉시성에 대한 직감적인 반응을 위해 연주자들이 화합과 정확도에 대해 배운 모든 것을 발산하는 방식이었다. 슈타이네커는 이렇게 말했다. “순간 속에서 우리의 반응은 감성적입니다. 언어로 풀 수 있는 게 아니지요.”

연주에 대한 나의 반응도 마찬가지였다. 나는 악기에 대해서는 까맣게 잊은 채 음악의 경이 속에 흠뻑 빠져들었다.

내가 시대 악기로 연주된 말러에 대해 몰입한 것은 처음이 아니다. 1990년대 로저 노링턴이 교향곡 5번 연주를 시대 악기로 시도했을 당시에는 터무니없다고 느꼈다. 말러를 과거로 되돌린다는 건 악기가 얼마나 오래됐는지, 어떻게 연주하는지에 대한 게 아니다. 마치 지금 듣는 것과 똑같은 음을 다시는 들을 수 없는 축음기 이전의 사고방식을 이해하는 것이다. 말러는 현대의 빈 필하모닉 오케스트라의 완벽한 녹음에 진저리를 냈을 것이다. 그는 리허설마다 마음을 바꾸었다. 그의 음악은 생의 순간에 집중한다. 슈타이네커의 토블라흐 앙상블은 이를 달성한 것이다. 앙상블이 순회공연을 한다면 나는 목발을 짚고라도 그들의 음악을 들으러 뛰쳐나갈 것이다.

번역 evener

노먼 레브레히트 칼럼의 영어 원문을 함께 제공합니다 본 원고는 본지의 편집 방향과 일치하지 않을 수 있습니다

The day the Queen died I was supposed to be in the high Dolomites, listening to young musicians wrestle with Gustav Mahler’s ninth symphony on original instruments. Mahler composed his last two symphonies in the summers of 1909-10 near the mountain resort of Toblach (Dobbiaco) and, while he did not live to hear them performed, he knew exactly how he wanted them to sound. Mahler was a stickler for timbre. As Director of the Vienna Opera, he replaced all the orchestra’s wind, brass and percussion instruments, declaring them unsuited to the volume, velocity and sophistication of Richard’s Strauss’s shocking new operas and his own universalist symphonies, drifting as they were to the brink of atonality. Other traditions were left unchanged. His violinists used no shoulder rest and cellists played with a short pin, yielding less hand-made vibrato but morestage-floor vibrations. The halls Mahler occupied were rectangular, producing a tighter acoustic than a modern hall, geared to flexibility. Mahler tailored every performance to the state of the hall. ‘If (my music) doesn’t work,’ he told the young Otto Klemperer, ‘change it. You have the right – no, the duty – to change it.’ He was also fond of saying that the music ‘is not in the notes’. Every player and listener must figure out where to find it. Human agency is paramount in Mahler performance; instruments don’t matter that much. So it was with a frisson of curiosity that I packed my bags for a short flight and two non-connecting trains to Toblach, only to crack my knee and collapse on a sofa, where I spent the week mourning the Queen and watching The Queue when what I really craved was to hear Mahler played in a manner as close as possible to what might have been his style. This idea was initiated by Philipp von Steinaecker, a cellist in the Mahler Chamber Orchestra who thought most conductors were getting it wrong. In pursuit of the real Mahler, Steinaecker dug out the composer’s purchase notes at Vienna’s Kunsthistorisches Museum and set out to find the instruments he ordered. One by one, he sleuthed horns and oboes in organ lofts, antique shops and military bands. Some he bought on eBay for next to nothing, others in auction rooms for a small fortune. Early 1900s instruments differ materially from current models. The metal is thinner, the cylinders narrower and the keys fewer, making precision much harder to obtain, and often unobtainable. It is reasonable to assume that Mahler did not need to have every note nailed on the head. ‘If we let them, the instruments teach us something about the sound,’ says Steinaecker. A this academy in Bolzano, near Toblach, he tried out his theories on students. Next, he recruited professionals from the Mahler Chamber Orchestra and from towns where Mahler once worked- Vienna, Prague, Leipzig, Kassel, Budapest, Hamburg, Amsterdam and Ljubljana. For the better part of a year he bombarded musicians with radical notions about how not to play Mahler. ‘Instruments have changed in the last 110 years,’ was his mantra. The Mahler we hear is not what he heard. Mahler spent his Toblach summer months in a bare wooden hut, overlooking a lush green valley and irresistible mountain trails that doctors had forbidden him to ascend. Fated by a cardiac weakness, he filled his last symphonies with intimations of approaching death. The ninth symphony opens with a hesitant beat that some conductors argue is a stethoscopic echo of his diagnosis(cardiologists I have consulted dismiss this as ridiculous). Along with other myths of the ninth symphony, it seemed plausible to me that contemporary instruments might reveal more of Mahler’s intentions. The symphony confronts fate and never blinks. One day an eagle flew into the hut, leaving Mahler cowering behind the piano until it left. There is terror in this symphony at the force of nature, along with a transcendence in the finale that promises an unbroken continuum of life and death. How might its composer have intended us to receive it? ‘The truth is we will never know,’ says Steinaecker, but his original-instrument performance at Toblach, delivered to my London sofa by soundcloud, proved consistently thought provoking. A blurrier attack adds a wooshy, numinous dimension to the opening. Unvibrated strings create an enveloping immediacy. The string players, it is clear, have listened to early recordings of Arnold Rosé, Mahler’s concertmaster and brother-in-law, and know when to add a soupy swoon. I loved the raw reediness of the flutes and oboes and was physically shocked by assaults on animal-skin drums, made by the family of Mahler’s own percussionist. But the essence lies in how players shed everything they had been taught about unison and accuracy in favour of a gut response to the immediacy of this masterpiece. ‘In the moment, our response is emotional – not philological,’ said Steinaecker. My response to the performance was much the same : I forgot about the instruments and lost myself in the marvels of the music. This was not my virgin immersion in period-instrument Mahler. When Roger Norrington had a go at the fifth symphony in the 1990s, I found it preposterous. Taking Mahler back in time is not about the vintage of instruments and how they are played. It is about entering a pre-gramophone mind set where what you hear will never sound the same again. Mahler would be appalled at the recorded perfectionism of the modern Vienna Philharmonic. He changed his mind from one rehearsal to the next. His music is about living in the moment. That’s what Steinaecker’s Toblach ensemble achieved. I will run out on crutches to hear them if they ever take to the road.

글 노먼 레브레히트

영국의 음악·문화 평론가이자 소설가.

‘텔레그래프’지, ‘스탠더즈’지 등 여러 매체에 기고해왔으며, 지금 이 순간에도 자신의 블로그(www.slippedisc.com)를 통해 음악계 뉴스를 발 빠르게 전한다

——–